Genre: Sci-fi Comedy

Premise: A plucky teenage boy is accidentally sent 30 years into the past, where he inadvertently prevents his parents from meeting, in the process threatening his very existence.

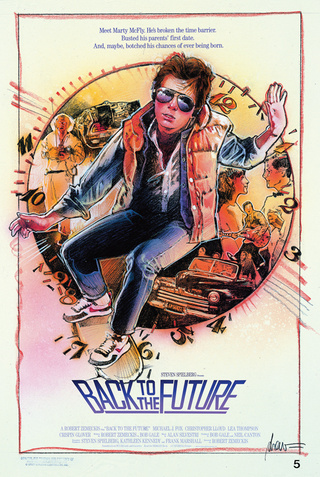

About: This is the very first draft of Back to the Future, written in 1981.

Writers: Robert Zemeckis & Bob Gale

Details: 110 pages (but the formatting here is really tight – this feels more like 130 pages) 1981 draft

I swear. I tried to see Thor 2 this weekend (as I said I would in my newsletter). With every fiber of my being I tried to go. At one point I actually constructed a catapult on my couch (from nearby items like couch pillows and a floor lamp) that would physically propel me towards the door so that I’d be forced to go.

But in the end, I just couldn’t (make the catapult work or see the film). I never did get into the whole Greek God thing in English anyway. Much like my distaste for Doritos and Everybody Loves Raymond, they were wisps of popular culture I never understood.

Instead, I decided to do something different today – read the first draft of Back To The Future! From what I’d heard, it wasn’t very good. The word on the street was that every studio in town passed on it. True, neither Zemeckis or Gale had done much at the time (Zemeckis’s first movie, Used Cars, had just come out and done so-so at the box office) but even if they had, nobody was drinking the McFly juice yet.

And therein lies the reason I must review it. I want to show screenwriters what can be done with a bad script. As long as there’s a good idea at the core, you can turn something bad into something good. It takes time (it took these guys 3 years). But if the script has potential and you’re willing to put in the work, there’s hope.

Back to the Future Alpha is essentially the boring version of the movie you’ve come to love. The script starts off strangely with Marty McFly perfecting his video pirating skills. He’s even trying to get Doc to streamline his bootlegging process so he can sell films out on the street before they hit theaters! I’m not kidding. And this is 1981!

Marty hangs around Doc’s place before and after school, shooting the shit. Doc’s always talking about power sources and how he needs more power for his latest project – oh, and there’s a secret locked room that he refuses to allow Marty to see.

Marty’s parents are both here, but their personalities haven’t been fleshed out yet. Likewise, Biff is operating on about 25% of his eventual personality. Marty’s still got a girlfriend (her name’s Suzy) whom he passes notes to in long classroom scenes where the teacher warms about the upcoming nuclear apocalypse. There are no siblings here, though (and therefore no famous disappearing picture).

One day Marty’s hanging out at Doc’s and, out of curiosity, pours some Coke into one of his devices. This causes a chemical reaction that turns out to be exactly what Doc needs for his mysterious behind-the-locked-door project. Coke (due to its secret formula) actually plays a big part in this version of the story.

We finally learn that the thing behind the door is a time machine. It needs incredible amounts of energy. And the mix of Coke and plutonium generate that energy. There is no car here. No 88 miles per hour. Just a machine in a lab. CIA agents eventually show up at that lab looking for the plutonium Doc stole. There’s a shoot out, and Marty accidentally gets caught in the machine and travels back 30 years.

After realizing where he is, Marty runs to his mom’s house and she’s, of course, his age now. He asks her what’s going on. She doesn’t know what he’s talking about or who he is. Marty passes out and when he wakes up, Doc has come to pick him up (Marty had Doc’s name in his pocket from earlier, so they called him).

Doc seems to know what’s happened right away in this version (Marty doesn’t need to convince him he’s from the future), and sets about getting Marty home. He tells Marty he MUST stay in his house in the meantime so he doesn’t upset the space-time continuum. But Marty gets bored and heads to school (because, why not!) where he sees his mom again, who starts falling in love with him.

From that point on, everything happens pretty much the way it happens in the film, except for the final sequence, where instead of the clock tower, we get Doc and Marty driving to Nevada to channel energy for the time machine from the very last nuclear bomb test in America. And in a sequence that would come back to haunt moviegoers worldwide three decades later, Marty will have to hide inside a refrigerator to survive the nuclear blast.

The biggest change you see from this draft to the final one is that of URGENCY. Everything in the final draft MOVES FAST. Characters are always late. Characters are always on the move. Characters always have somewhere to be.

In this version, Marty’s just hanging out at Doc’s place with all the time in the world. Then he’s hanging out in his classroom with his teacher droning on about nuclear bombs. The story ISN’T MOVING. It’s GETTING READY TO MOVE. And that’s one of the major things that rewrites change. You locate all the places in your story that are GETTING READY to happen, and you replace them with things that HAPPEN.

Take Doc’s time machine, for instance. In this version, Doc’s still in the process of building it. He hasn’t come up with all the answers yet. This means four or five scenes of Doc wondering how he’s going to do it. In the movie, DOC’S ALREADY FIGURED THIS OUT. He already has the time machine ready. So the story’s already on the move. He calls Marty to the mall and we’re off to the races.

Or look at the classroom scene. The final draft would NEVER have a classroom scene. Characters sitting around while a teacher slowly doles out exposition? No way! Instead, Marty’s late for class. He’s getting stopped in the hallway by the principal. He’s trying to set up his date with Jennifer. We don’t have time for class! There’s always somewhere to be!

You also see a lot of forced set-ups here, which is one of the easiest ways to spot an early draft. Take Marty’s skateboarding. Obviously, one of the key scenes in the film is when Marty outmaneuvers Biff in Town Square on a makeshift skateboard. So we need to set that up. In this version, in the first act, Marty is walking home with Suzy and some kid’s skateboard shoots off towards Marty. Marty hops on it, does all these ridiculous tricks for no reason (other than to set up he’s a master skateboarder), then hands the board back.

Contrast that with the final draft. The skateboard is an integral part of Marty’s everyday routine. It’s how he gets around. We see him hop on it and hurry to school as early as the second scene of the film. That’s one area where rewriting helps, is taking those isolated ideas and interweaving them into the fabric of your screenplay.

The same thing can be said for stuff like the Clock Tower, the lightning bolt, the car-as-time-machine, the 88 miles per hour. We saw seeds of those ideas here, but they needed time to grow in order to be realized. Doc is living in the main building in town, which looks like it eventually became the Clock Tower. And the idea of them only getting one shot at this lightning bolt originated from the one and only shot at catching energy from the nuclear bomb test.

Speaking of the ending, that was another huge problem with this draft. You don’t keep your characters in one location for 90% of the movie, then put them in a car and drive them on a six hour road trip for the climax. It feels clumsy and disjointed. I’m guessing Zemeckis and Gale eventually realized this, which necessitated a more local solution. Hence the atomic bomb turning into a lightning bolt.

Also of note is the movement of a key plot point that really helped the structure of the second act. In this version of Back To The Future, Marty doesn’t disrupt his parents from meeting right away. Instead, he runs into his mom, then goes to Doc’s, then Doc tells him to hang out while he works on sending him back to the future.

Despite Doc hammering Marty on how dangerous it is to interact with anybody, Marty leaves the house and heads to school out of boredom. It’s only then that he screws up the meeting between his mother and father. This, of course, makes zero sense. Why would Marty go to school and potentially endanger his existence if he doesn’t have to?

In the final draft, they wisely changed the position of this plot point to maximize motivation. Marty saves his father after he falls out of the tree, getting hit by the car INSTEAD of his dad, and getting taken into his mom’s house, where she falls in love with him (instead of his father). All of this happens BEFORE he meets Doc. This way, when Marty and Doc game plan sending him back, they realize that Marty has already endangered his existence by having his mom fall for him instead of his dad. Marty now HAS NO CHOICE but to go to school and correct his mistake. This works so much better than, “Eh, I’m bored. Let’s go to High School.” Right?

I think to some of you, all of this is obvious. “Yeah, it was an early draft. Of course it wasn’t as good as the final draft.” But this is the draft Zemeckis and Gale were originally trying to sell. And that’s the problem. I see a lot of writers going out there with drafts like this. Drafts with huge potential but where the writers haven’t come close to maximizing that potential.

Think about it. Is your ending the refrigerator-in-a-nuclear-explosion ending? Or is it the Delorean racing 88 miles per hour while Doc swings from the clock tower lightning bolt ending? Sure it takes lots more drafts and lots more time to get the lightning bolt ending, but how the hell do you think you’re going to beat the competition with a subpar product?

I don’t think this draft of Back To The Future was bad. But it reads like a lot of early drafts do. Some fun ideas. Some decent characters. Some clumsy exposition. A start-and-stop story that’s still trying to find itself. But it didn’t feel FINISHED.

The lesson here is to look at what can happen when you rewrite. I heard stories about how these two, after getting rejected, wrote draft after draft after draft of this script, debating every single detail of the story until it got to where it needed to be. That takes dedication. And that’s what every screenwriter needs in order to succeed.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Every time you get an idea, it’s just a seed. Your job is to water that seed and help it grow to as big as it possibly can. Too many writers are too impatient to do the watering. And their scripts always reflect that.