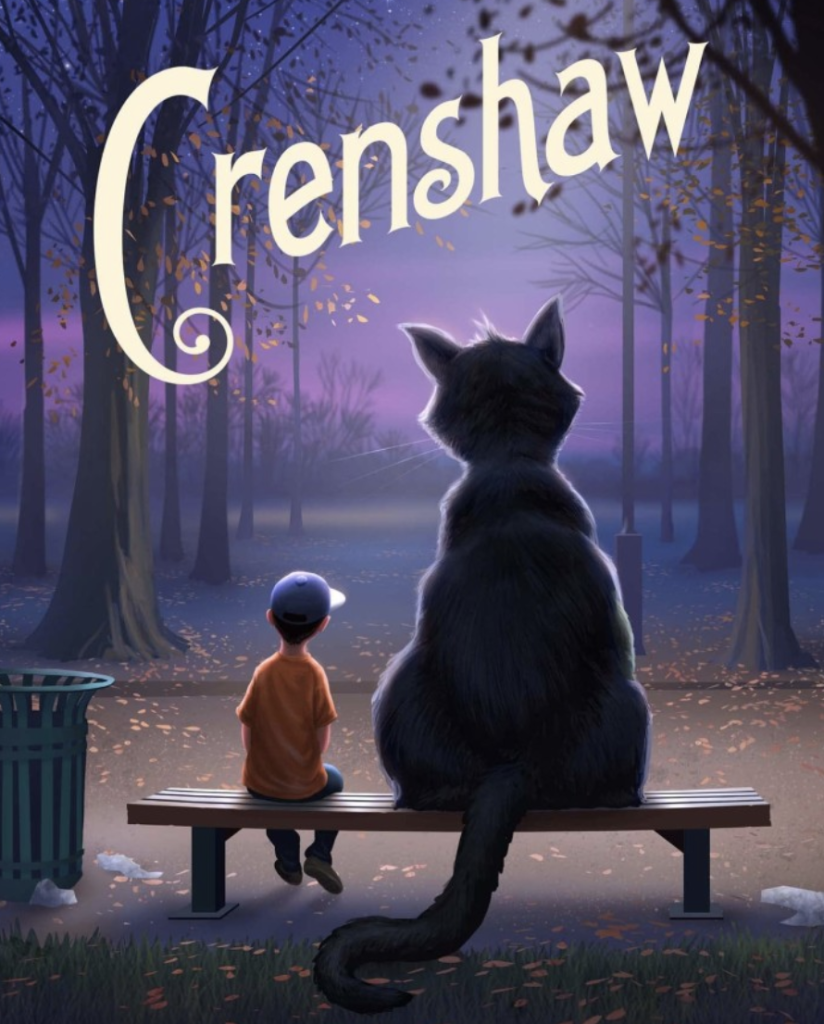

Genre: Family/Kids

Premise: A 10 year old boy deals with his family’s extreme poverty by reconnecting with his old imaginary friend, a giant purple cat.

About: This is the first movie James Mangold signed onto after the success of Logan. It comes from unknown screenwriter Frederick Seton. The story is based on a popular children’s book by Katherine Applegate, who won the 2013 Newbery Medal for her children’s novel, The One and Only Ivan.

Writer: Frederick Seton (based on the book by Katherine Applegate)

Details: 118 pages

I always find it interesting when directors known for dark material make kids films. Cause you know it isn’t going to be your typical kid’s film. Not to mention, dark kids films are the ones that stick with you for life. From Willy Wonka to Coraline to The Dark Crystal to Time Bandits to Where The Wild Things Are. That’s what I’m expecting when I see James Mangold (Logan) directing a family film.

By the way, I always tell screenwriters that if you want to learn how to write a screenplay, write a kid’s film. Kids movies teach you all the things you need to learn in order to write a good story. They require you to build sympathy for your main character, establish a character so that we instantly understand them (think John Connor hacking an ATM machine in T2), how to set up a goal that drives the story, how to establish high stakes, how to write in three acts, how to apply a theme, how to arc a character.

The great thing about kids films is that they’re a lot more forgiving because the audience isn’t as discerning. Let’s say you go over the top in establishing that your hero’s main flaw is that he’s selfish. You won’t get dinged on that compared to if you did so in an adult drama. Which makes this genre a great training ground.

“Crenshaw” follows a 10 year old boy named Jackson whose parents, Thomas and Sarah, are reallllllly poor. Jackson loves facts, which he spits out randomly to anyone who will listen: “Did you know that most adult moths don’t eat? Some don’t even have mouths. They’re just alive to make more moths and then they die.”

He, his parents, and his younger sister, live in a tiny house with tinier rooms and the tiniest of comforts. Both parents are unemployed, Thomas because he has MS and Sarah because she lost her job recently. What that means is they’re weeks away from losing the house, in which case they’ll have to, once again, live out of their old VW van.

One day, while Jackson is at the beach, he spots a giant purple cat surfing. This is Crenshaw, an imaginary friend from when Jackson was 5 years old. Crenshaw speaks with a British accent and cares mainly about having fun and helping Jackson. Jackson’s number one priority at the moment is getting a present for a friend’s birthday party. Because Jackson doesn’t have any money, he doesn’t know how he’s going to buy the present.

Meanwhile, Jackson’s parents are prepping for a garage sale, in which they hope to make enough money to keep their house. Sarah clearly doesn’t think the garage sale is going to work. She believes that the only reason they’re in this predicament is because of Thomas’s pride. He refuses to ask others for help. Which means, barring some miracle, they’ll be homeless again soon.

Oddly, Jackson and Crenshaw never discuss this problem, focusing instead on the way less important birthday present they need to find. Crenshaw seems to randomly show up every 20 pages or so asking for an update. And he isn’t very helpful in getting this present. In fact, Crenshaw isn’t very helpful at all. In fact, I have no idea why Crenshaw is even in this movie. Suffice it to say, this was a mess of a story that didn’t seem to have a plan or a point.

The industry parlance for figuring out the story in your movie is called “cracking” it. Well, they definitely did not crack Crenshaw. There are more problems with this screenplay than I can count. Luckily, there’s a lot to learn about what not to do in a family movie… or any movie for that matter. Let’s go down that list, shall we?

Jackson has zero influence on the story. He doesn’t do anything. He waits around, complains some. But he’s not contributing to the main problem facing him – which is that his family is going to be homeless soon. A main character who doesn’t act, who doesn’t have any control over where the story goes, is a weak character.

If I stopped there, that’s still enough to sink a screenplay. You need your main character to be active and to be doing things that solve the central problems he’s faced with.

There isn’t really a plot here. There are two things driving the story (technically speaking). One is the birthday present he has to buy. The other is them potentially losing their home. Let’s start with the present. The kid who invites Jackson to his party clearly likes him. For that reason, the gift doesn’t matter. You never get the sense that the friend will treat him differently if he comes without a gift.

This is why I say family scripts are great training grounds because this is where you learn this stuff. The stakes are low. So how do we make them higher? Well, what if this kid never wanted to invite Jackson? What if he only invites him because his parents make him? Under that scenario, Jackson’s present now matters. He wants this kid to like him. He feels like if he can get him the perfect gift, he’ll win over his friendship. That choice alone would improve this script by 20%.

As far as the homelessness, it’s dealt with in a really weird way, where it sort of pops up for ten pages then disappears for fifteen. It pops up again. Then it’s gone. Due to this inconsistency, it doesn’t feel important, which leaves very little gas in the plot tank.

You want to think of your screenplay as a car. But, unlike a car, which runs on regular gas, a script needs “plot point gas.” It needs a series of plot points to propel it along. Without those plot points, the car/screenplay isn’t going anywhere.

For example, in the recent movie, 8-Bit Christmas, which follows a kid who’s trying to get his dream Christmas present, a Nintendo Entertainment System, one of the plot points in the second act is the Boy Scouts are giving away a first place prize of a Nintendo to the scout who can sell the most Christmas wreaths. That plot point propels the characters to do something (sell wreaths) which pushes the plot along.

There don’t seem to be any plot points that develop along the way in regards to losing the house. It’s spoken of generally, leaving it up to the reader to figure out when they’re losing the house and what they’ll do afterwards.

I guess this isn’t surprising considering “Crenshaw” doesn’t even pass a basic storytelling smell test. Why have a titular imaginary cat that doesn’t affect the story? Doesn’t try to fix the problem? Doesn’t help the main character do anything? It’s bizarre how little both he and Jackson have to do in this movie.

Although there are all sorts of problems with this script, the main one boils down to a weak plot. The writer sets two goals – a present for a birthday party and a family about to lose their house – and doesn’t seem interested in resolving either one. For a story to work, the main character must be desperate to solve the problem. That will make them active. And their activity will ensure that there’s always something going on in the plot. If they’re only kind of invested, as is the case here, you’re going to put your audience to sleep.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This is a trick I’ve learned through reading a lot of family scripts. When you have an animated character, such as Garfield or Clifford or Sonic – mention a well-known actor/personality to convey what the character sounds like. To see how effective this is, let’s say I wrote a movie about a talking mouse named Lenny. “Lenny sounds like Will Ferrell.” “Lenny sounds like Morgan Freeman.” “Lenny sounds like Morpheus from The Matrix.” “Lenny sounds like Ryan Reynolds.” “Lenny sounds like Matthew McConaughey.” Note how each person mentioned gives the character a distinct identity that helps you immediately understand them. I wish Crenshaw would’ve done this because I never quite knew what he sounded like.