Genre: Western

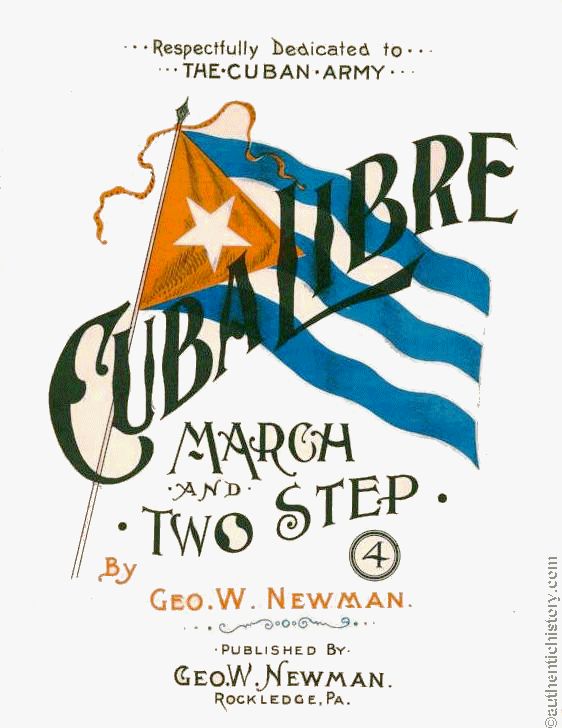

Premise: In 1898, on the brink of the Spanish-American War, a bank robber shuttles a herd of horses into Cuba for a big payday.

About: Cuba Libre is based on one of Elmore Leonard’s lesser-known novels. The Coen Brothers then adapted the book in 1997. It was later revised by Jay Cantor, a Harvard educated novelist whose novel about Che Guevara was described by one amazon reviewer as “Weird, disjointed writing and story. Nonsensical at times.” This will come into play later in the review.

Writers: Joel and Ethan Coen (based on the novel by Elmore Leonard) Revision by Jay Cantor

Details: 137 pages (September 16, 1998 draft)

The Coens are an up and down entity. They are capable of genius, but they’re also capable of buying into their own hype, resulting in movies that are too eccentric or personal for anyone but the most artsy moviegoer. For every Fargo, there’s a Ladykillers. For every No Country for Old Men, there’s a Burn After Reading. It can be frustrating, since the two are so talented. But you have to take risks if you want to blow audiences away, and they’ve certainly afforded themselves as many risks as they want.

Cuba Libre was written between the Coens’ two best movies – Fargo and The Big Lebowski. This is when these two were at the top of their game. So you’re figuring it’s gotta be good, right? A couple of problems though. The source material is far from beloved. And the script is revised by someone who had never touched a screenplay before. Might it all still come together? Let us hope. Cause it’s 137 freaking pages and I don’t want to read a bad 137 page script.

Cowboy Ben Tyler has just stolen 150 horses, which he plans to ship to Cuba, where the going price for a horse is 150 dollars, a ton of money back in 1898, and twice as much as he’ll get anywhere in America.

Thing is, when Ben gets to Cuba, the businessman he struck a deal with, an American sugar magnate named Boudreaux, switches up the terms on him. Says he’s only going to pay 100 a horse. Boudreaux is used to men crumbling in his wake. But Ben isn’t that kind of cowboy. He tells Boudreaux to fuck off and considers selling the horses to the local Cubans instead.

Just to show that there’s lots of hard feelings, he charms Boudreaux’s girlfriend, Amelia, into joining him. Meanwhile, Ben has also smuggled some guns over that he plans to sell to the Cubans in their battle against the Spanish, news that finds its way over to the Spanish camp, making Ben a hot commodity in their eyes as well.

Soon, Ben’s got the Cubans after him (for the horses), the Spanish after him (for the guns), and Boudreaux after him (for Amelia).

This might’ve worked if Leonard, the Coens, and Cantor had stopped there. But they also try to cover the beginning of the Spanish-American War, as well as insert a Fargo-esque fake kidnapping scheme (of Amelia) to get Boudreaux to pay Ben 80 thousand dollars. All of these things come to a head in a final giant train chase for the money, the guns, and the girl.

Cuba Libre is a classic example of trying to do too damn much. Screenwriters – you have to understand the limitations of your medium. You can’t pack a story that needs 480 pages to tell into 120 pages (or, in this case, 137). You have to step back, cut storylines, cut characters, and keep things focused.

We have so much shit going on here. A bank robber smuggling horses into a foreign country. A secret plot of smuggling guns into the country. A sugar empire. Cubans fighting the Spanish. The Spanish preparing to fight the Americans. A kidnapping plot. An assassination plot.

Screenplay-loving Pixar has a saying – Simple story, complex characters. Cuba Libre sure could’ve taken heed of their slogan.

My guess? Jay Cantor went all “novel” on this. He tried to jam a 5 inch brad story into a 2 inch brad script. Amidst everything I mentioned above, our heroes are also travelling hundreds of miles inside of Cuba, walking around aimlessly and talking about nothing. At one point, so little had happened for so long that I leaned back, squinted my brain, and said, “What the hell is this about anymore!!??”

If I could give screenwriters one piece of advice it would be “Get to the point!” Too often writers get lost in meaningless tangents. The audience isn’t interested in tangents. They want to know what the characters are trying to do, they want meaning behind that pursuit (stakes) and they want there to be some urgency behind it.

It wasn’t until the final act that this actually happened. In a signature Coen Sequence, a late train chase has all the characters going after a bag of money. FINALLY, we understood the goal (money). We understood the stakes (Ben and Amelia needed the money to escape the country together). And we understood the urgency (they only have until the next train stop). Before that, if you quizzed me on what everyone wanted at any particular time, I wouldn’t have had any idea (Yeah, I summarized the plot above, but 50% of that was guesswork based on what I thought the writers were trying to do).

Our scribes didn’t help their cause by creating four character factions (good guys, bad guys, Cubans, Spaniards). It’s not that you can’t do this, but the more groups you add, the more difficult it becomes for the reader to remember who’s who and who wants what, especially in a case like this, where some groups had both good and bad sub-groups. For example, one of the Cuban generals was mean. The other was helpful.

In the cases where I’ve seen multiple-factions work, the writers work tirelessly to keep everything clear. Take Empire Strikes Back, for instance. The bounty hunters (which included Boba Fett) were their own faction, but we met them with the Empire. We see Darth Vader assign them to find Han Solo. So we understand that they’re part of the bad guy alliance. Had we not met them with the villains, but rather flying around looking for Han on their own, we probably would’ve been wondering who the hell they were. Since Cuba Libre was so sloppily executed, every faction oozed ambiguity. Who worked for who? Who wanted what? Who the hell knows!

That’s not to say Cuba Libre was a total bust. The Coens writing would occasionally shine through. Actually, there was a great scene early on that made me remember yesterday’s script, The Strain, specifically what it needed to do more of.

In the scene, Ben finally makes it to Boudreaux, the man who’s agreed to buy his horses, and prepares to collect his money. In The Strain, this scene would’ve gone exactly according to plan. Ben would’ve said here are your horses. Boudreaux would’ve paid him exactly what he was asking for, and Ben would’ve gone on his merry way.

Instead, in this version, Boudreaux looks at the situation – that this man has travelled a thousand miles to his island and has no other options – and says, “You know what. I don’t want to pay 150 dollars a horse anymore. I want to pay 100.” This is how to approach screenwriting. Things should never go according to plan.

Think of movies as the opposite of life. We LOVE for life to go according to plan. It means breezy days and relaxed evenings. But in the movies, if things go according to plan, the audience is bored. Who wants to see a bunch of shit go right? So when you approach an act or a scene or a beat, you need to ask yourself, “How can I screw this up for them?”

And the bonus with this approach? You know how yesterday I was talking about the importance of creating choices for your characters? Giving them difficult decisions that force them to act? When you screw up the hero’s plan, you force them to make a choice. Once Boudreaux changes the terms, Ben now has to make a choice. Does he accept the reduced rate or does he play hardball and leave? Each option has consequences and neither is very good. Whatever Ben chooses, it’s going to tell us a lot about him, right?

Anyway, Cuba Libre was a sprawling mess that had infrequent moments of genius. Swinging for the fences is great. But Holy Chesapeake Bay, don’t fill your script with more than you have to. You can still write something complex without including EVERY. SINGLE. IDEA. YOU HAVE. Screenwriting, in many ways, is about showing restraint.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you’re going to include a lot of character factions in your script (not just the good guys and bad guys), make it easier on yourself by having everyone chasing the same thing – or, as George Lucas likes to call it, a MacGuffin. In Star Wars, everyone’s chasing that damn robot with the Death Star plans (R2-D2). So even though there are a lot of different people, we’re always clear on what they want. Cuba Libre’s problem is it had four different factions who each wanted four different things. It was too much information to keep track of. Only storytelling masters with a deft command over clarity can pull that off.