Genre: Drama/Crime

Premise: (from IMDB) When two overzealous cops get suspended from the force, they must delve into the criminal underworld to get their just due.

About: S. Craig Zahler is somewhat of a screenwriting legend. At one point he’d sold over a dozen [unproduced] screenplays. Since then, Zahler’s graduated into directing, and his newest project is the delicately titled, “Dragged Across Concrete.” Sounds like a biopic about safe spaces. Zahler will be bringing back the star of his previous film, Vince Vaughn, as well as adding Mel Gibson to the mix (who it was announced yesterday is directing a remake of The Wild Bunch). Concrete is already poured and is slated to come out later this year.

Writer: S. Craig Zahler

Details: 157 pages!

If you’re new to the site, take a look at the right panel where I’ve listed my Top 25 favorite scripts. You see number 3? That was written by this guy. S. Craig Zahler has one of the most powerful literary voices in the screenwriting community. When you’re reading a script by Zahler, you know it instantly. While that’s a big advantage in the spec world, it can be a roadblock in the “get movies made” world. Studios don’t really know how to pair up unique voices and directors. This is why most voice-y screenwriters direct their own material (Tarantino, Sophia Coppola, Wes Anderson, Paul Thomas Anderson). It took Zahler a long time to realize that. But once he did, his career trajectory shot up. He started with Bone Tomahawk, moved on to Brawl in Cell Block 99. And now he’s going to drag some poor soul across concrete. Let’s see how he did, at least on the writing end.

20-something Henry Johns has just got out of prison to find that his mother has taken up prostituting herself and using all the money to shoot heroin into her veins. Not a good look since she’s supposed to be taking care of Henry’s little brother. With no work prospects on the horizon, Henry knows that the only way he’s going to flip this situation around is by plunging back into the crime world.

Across town, cops and long-time partners Brett and Anthony are dealing with their own issues. Anthony’s thinking of proposing to his girlfriend despite suspicions that she’s not that into him. And Brett’s dealing with a wife who’s struggling with MS, and a daughter entering puberty, which has gotten the attention of all the boys in the yard, that yard being located in one of the worst neighborhoods in the city.

Things come to a head during a routine bust when Brett is videotaped roughing up a perp. The video goes viral and gets the both of them suspended for six weeks without pay. Sick and tired of his shitty life, Brett decides to do the unthinkable: Use a criminal contact to find out where the next big drug deal is going down. His plan is to come in when they least expect it, take the money, and head to greener pastures with his family. While Anthony isn’t as keen on the idea, he wants to help his friend.

So Brett and Anthony stake out the dealer’s home, and when the crew finally arrives, we notice that one of the dealers is Henry Johns. Our off-duty cops follow Henry and his crew to the exchange spot, except something is off. It turns out they’re not doing a drug deal. They’re robbing a bank. Brett thinks of calling an audible until he realizes that the payday is going to be 10x what he originally assumed.

Brett and Anthony wait for the thugs to finish the job before following them home. All parties end up at an abandoned gas station, where a wild showdown occurs. People start double-crossing each other while others are forced into temporary alliances. Despite Brett doing everything in his power to get that money, it becomes clear to us that the only person who’s going to make it out of here alive is Father Greed.

The first question you’re probably asking is, “How did you make it through 157 pages, Carson?”

It wasn’t easy.

For sometimes better and sometimes worse, Zahler likes to draw out his stories. You love it when he’s setting up rich characters with complex relationships. You hate it when he extends what should’ve been a 2-minute scene into 15 minutes of “well that could’ve been shorter.”

I mean the stakeout sequence is 10 pages long. You don’t need that. That’s not to say you can’t draw out certain scenes. But the degree to which you can stay with a scene is directly proportional to how interesting the situation is. A stakeout is boring. So of course we’re going to be bored if we sit around for 10 minutes.

On the flip side, the next scene, where they discreetly follow the criminals to their rendezvous point, felt perfect at 15 pages. Why? Because there’s an ongoing sense that they might be spotted. Because the characters we’re watching have a high-stakes goal. Because a mystery emerges about what the criminals are actually up to. Better situations can be extended out.

This was an issue I had with Brawl in Cell Block 99 as well. It was taking too long to get to the point of the movie. All the best stories (in any medium) become interesting once a problem arises. If I tell you a story about my drive through Death Valley and I never introduce a problem, you’re either going to tune me out or tell me to shut up. If I tell you a story about driving through Death Valley and then my car breaks down in the middle of nowhere on the hottest day of the year (a PROBLEM), you’re going to be captivated. Stories don’t start until there’s a problem.

The “problem” in this story, which I would argue is when Brett realizes he needs to get his family out of this neighborhood, doesn’t come up until 50 pages into the script. While I’ll never say that certain plot points need to happen by certain page numbers, every page after page 15 that you don’t introduce the central problem of your story is dramatically increasing the likelihood that the reader is going to tune out.

In my case, I knew this going in, because I know Zahler’s writing so well. That allowed me to stick with the script longer than I typically would. And once we get to the problem, the movie picks up considerably. Actually, you could make the argument that a lot of those scenes that seemed arbitrary at the time became essential anchoring points.

For example, we meet Sara, Brett’s 12 year old daughter, walking home from school in a shitty neighborhood. A few boys harass her, and we get the sense that just walking home for this girl is dangerous. It’s a good scene but all I could think was, “This is a long script. Can’t we cut this scene out?” However, later, when Brett’s wife makes the argument that things are only going to get worse for Sara if they stay in this neighborhood, us experiencing Sara’s harassment becomes critical in understanding why Brett makes the choice to steal money.

Not to mention, the climax makes all the setup feel worth it. It was a clever move by Zahler to introduce Henry Johns early, ignore him for the first half of the second act, then bring him back as a point man in the robbery. Creating complicated scenarios where we’re not sure who we’re rooting for – the good guys or the bad guys – isn’t easy to do. That legwork of setting up both Brett’s and Henry’s shitty lives – even if I was bored watching them at the time – paid off in that I wanted both of them to succeed, something I knew wasn’t going to happen, which is exactly why I was so drawn in.

Despite that being well-done, I still think Zahler’s too self-indulgent. Even five minutes in a movie is an eternity. You can get any point across in 5 minutes. But with Zahler, he’ll double that without a second thought. And while these endless scenes never derail the movie, they certainly wreak havoc on the pacing. I hear the director of The Outlaw King cut 20 minutes off his movie after the negative test screening at TIFF. I would suggest Zahler do the same. You don’t want to waste a movie with character work this strong.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

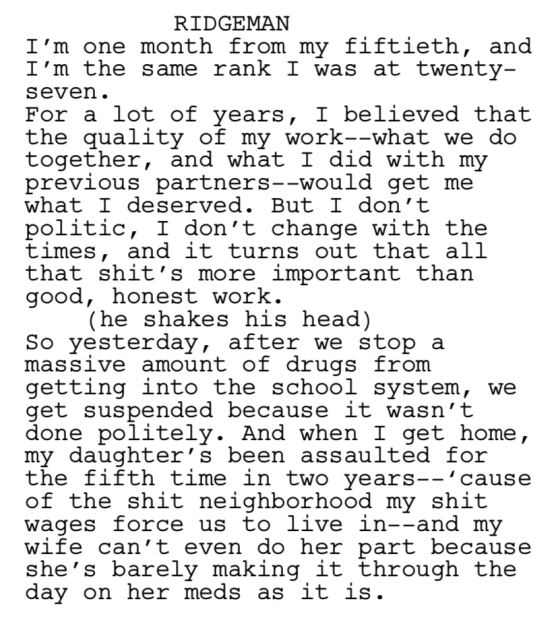

What I learned: The stronger the motivation, the more we’ll root for your hero. I love how we get Brett’s motivation in a single monologue. Anthony is pressing him and pressing him and pressing him on why he’s risking everything for this money. Brett finally cracks…

What I learned 2: Now some of you might say, “But Carson! Isn’t that on-the-nose dialogue!?” No! It isn’t. Don’t you guys remember last week’s dialogue article? Number 2? A character can reveal backstory (or other exposition-driven information) as long as he’s pushed into it.