Genre: True Story – World War 2

Premise: (from Black List) Famed artist M.C. Escher reluctantly uses his unique view of the world to help the Dutch Resistance fight Nazi occupation during WWII. Inspired by true events.

About: This script made last year’s Black List! Jason Kessler worked as a writer’s assistant on the show, Madam Secretary.

Writer: Jason Kessler

Details: 98 pages

In honor of the unveiling of the trailer for World War 2 movie, JoJo Rabbit (script review here), I present you with…. ESCHER! Actually, I chose “Escher” because it had the potential to be a unique look at the war. We’re talking about one of the most famous illusionists ever. So surely we were going to get something different, right?

It’s the Netherlands in 1944 and many Dutch Jews are being forced into hiding. The German war machine is at its apex, leaving Amsterdam heavily occupied. 46 year old artist, M.C. Escher, has somehow managed to make a living off his trippy drawings, which are popular with the Germans. As a side job, he drives out to local farms and stocks up on vegetables, which he gives out to those in need.

One day, Escher’s brother, Berend, takes him to his son, Rudolf’s, place. Rudolf fights for the resistance. He asks Escher if he can start coming along to the farms. They need to hide more Jews and they’ve run out of places to hide. Escher reluctantly agrees, only because his good friend’s daughter, Elizabeth, will be in need of the service.

Escher wants as little contact with the resistance as possible. However, once he starts helping them, they want more. Escher has access to one of the biggest German doctors in town, and they desperately need penicillin. Escher helps them get some, but they aren’t satisfied. So they go to the office one night and kill the doctor, taking the rest of the penicillin.

This leads the Germans to kill 10 innocent men, making Escher furious. Rudolf tries to explain that the penicillin they stole will end up saving more lives than they lost, but Escher isn’t buying it. Eventually, the Germans catch wind of the farm network and, in 72 hours, plan to raid all the hiding spots. This forces Escher and the resistance to create an intricate network of relocation, which will be tracked by an elaborate drawing he creates which only the resistance will understand. Will they succeed in time to save Elizabeth? Or will all this end up crashing down on Escher?

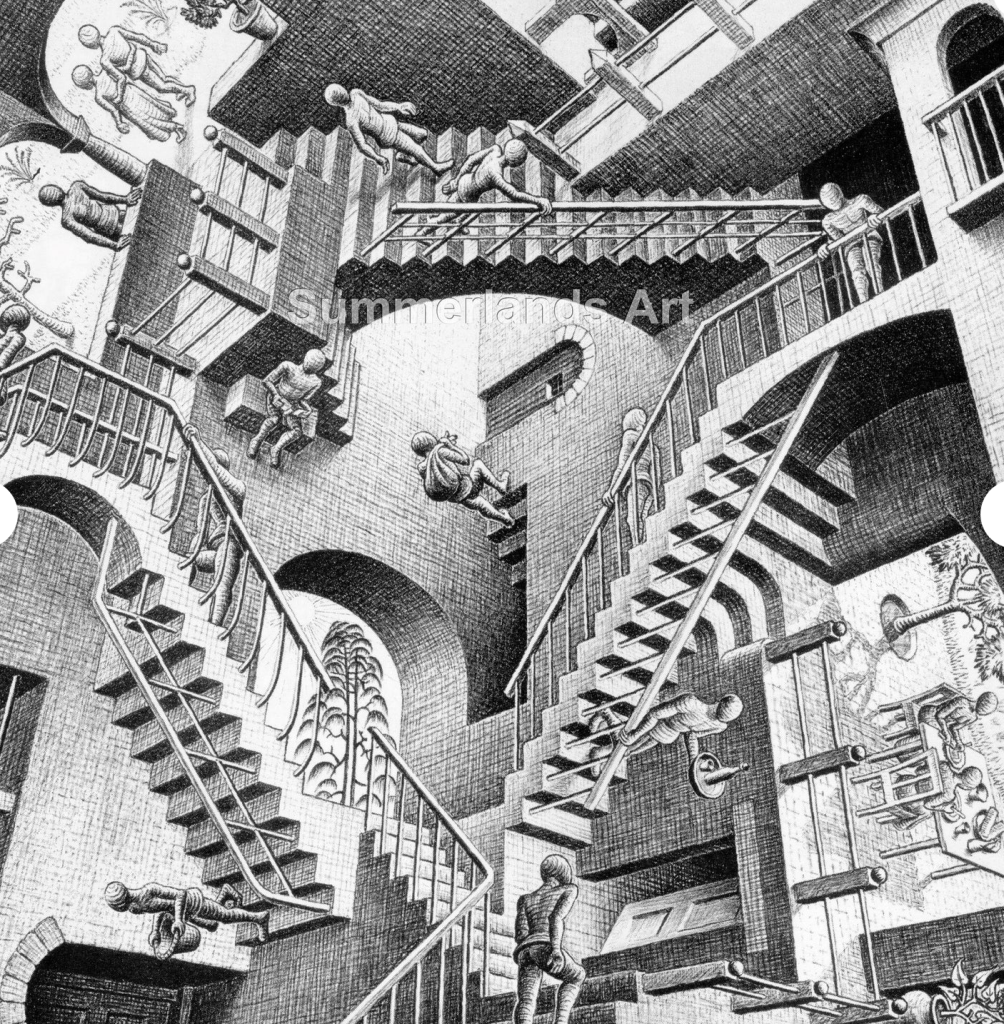

Naturally, when you read a script about Escher and World War 2, you’re expecting weird illusions to play a big part in the story. But there wasn’t as much of that as I had hoped. You had the coded Escher farm map that was keeping the Jews hidden. You had a dream sequence where German soldiers chased Jews inside Escher’s most famous work, “Relativity.” And there are a few sequences where characters become 2-dimensional drawings, not unlike what Escher would draw.

But it wasn’t like Escher’s talents were inexorably linked to the story. What surprised me about the script is that I actually got invested in the story itself. Early on, we meet this child, Elizabeth, who’s thin and malnourished, like a lot of Jews at the time. And yet when Escher brings her an apple, she insists on sharing it with her grandfather. So we immediately love this little girl.

Then, when the farm-hiding plotline revs up, it’s not a faceless endeavor. We know one of the characters who’s being hidden – Elizabeth. So every time it’s mentioned that those people are in danger, we think of her. And therefore, we care about what happens.

The script also gets surprisingly dark, with the people who Escher is helping going behind his back and taking advantage of him (by killing the doctor he knows for penicillin). This creates a morally complicated story where simply doing the right thing isn’t always an easy proposition. He has to think, if I help these guys, they might do something bad, and then more Jews might get killed. In so many of these scripts, it’s black and white. Save Jewish Character – good. Kill Nazi Officer – bad. There’s a lot more going on here.

This should stand as a great lesson for screenwriters. Saving people is more interesting when it’s complicated. When there are consequences involved. At one point Rudolf is literally doing the math for Escher to explain that, yeah, they just got a bunch of their people killed, but in the end, they’ll come out on top.

If the script has a flaw, it’s its main character. Escher rarely does anything of his own volition. Someone tells him, “You should do this,” and then Escher either decides yes or no. On top of that, you’re wondering if any of this is true. They tell us at the beginning “This film is an illusion. Some of it is real. Some of it is surreal. Escher would’ve liked it that way.” Maybe he would, maybe he wouldn’t. But when you’re talking something as dark and intense as World War 2, and you throw a known historical figure in there, you’d like to think that what you’re watching is more truthful than it is less truthful. I don’t want to go on some morality rant here. But it feels so much better when you see a movie like this and then you find out all those great scenes that you watched really happened.

The good news is, this is one of the few World War 2 scripts that I think deserves to be made. And I say that because a visual director could do wonders with this material. If you could somehow integrate Escher’s work into the visual aesthetic of the film? It would not only look amazing, but it would add an element that we’ve never seen before in a World War 2 movie. And how often do you get to say that? It’s a great reminder that, in the end, you’re not trying to write a script. You’re trying to make a movie. So you want to ask yourself, is this a movie the Hollywood machine would want to make? And I think this is. We’ll see what happens.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Reluctant heroes are harder to make work because they rarely take action on their own. They’re yanked around and asked to do things, like Escher is here. It’s not as if they’re uninteresting. The dilemma that comes with their choices – especially if those choices have life and death consequences – can be compelling to watch. But it’s always harder to get on board with a character who isn’t driving the story through their own actions. I just think at some point, even if your character IS reactionary, he needs to take the reins away from the other characters and make the horses go himself.