Genre: Legal Drama (True Story)

Premise: The life of a cynical San Francisco criminal lawyer at the top of his career unravels when he agrees to represent a father accused of killing his infant son in an extraordinary case that challenges widely accepted medical beliefs, a biased justice system, and his own personal worldview. Based on true events.

About: This is the second script in last year’s Black List that has three writers on it! The first was the script written by the Murder Ink trio, which I liked. These writers have begun to make some minor inroads into the industry. Nathan Gabaeff has a movie he wrote and directed called Avenge the Crows. His brother Isaac wrote a TV episode. But making the Black List appears to be their big break.

Writers: Thomas Berry, Isaac Gabaeff, and Nathan Gabaeff

Details: 121 pages

Carrell for Conlon?

Carrell for Conlon?

If it’s taken me this long to review a Black List script, it typically means there’s something I find questionable about the concept. With False Truth, the concept seems to be both too small and too misguided. Let me explain. The idea is small in that it could be a Good Wife episode. Courtroom thrillers used to be common until legal TV dramas pillaged all their scenarios.

This makes almost every courtroom concept today a TV episode in the audience’s minds. Back in the day, John Grisham was able to find a few big flashy legal cases that felt like movies. But, since then, we’ve had a few thousand television courtroom cases, so it’s super rare to find one that’s worthy of a movie canvas.

The other problem I have is that there’s no winning when the subject matter is a baby’s death. If the father wins the case, so what? His baby doesn’t come back to life. So all of us still lose. Can a concept get more depressing?

I was confused as to why anyone would want to write a movie about this until I got to page 28. That’s when I read this line: “But if it’s a shaken baby case there’s one guy you really want to get… Doctor Steven Gabaeff.” Gabaeff? Where have I seen that name before? It took me a moment but then I realized, wait a minute, this is the writer’s last name!

So, obviously, the writers knew someone – I’m guessing it’s their dad – who was involved in this case and because they have such intimate knowledge accessible to them about the case, they said, “We should write a movie about this.” The fact that the writers did have that connection made me more intrigued. But I still think it’s a tough sell with a concept like this. Let’s see if I’m wrong.

Jennie gets the worst call imaginable from her husband, Kristian, who’s just told her that their infant son is in the hospital because he dropped him. She races to the hospital where she gets updated. Her son is now in a coma (he eventually dies) and the doctors suspect that Kristian has attempted to kill his son with something called “Shaken Baby Syndrome.”

This is when you shake a baby too fast. Kristian is quickly carted off to jail and Jennie hires noted San Francisco attorney Elliot Conlon, a man who used to stand for things but now seems content with making a lot of money, no matter who the defendant is. That’s going to be pushed to the limit since he’s now defending a potential child murderer.

Conlon digs deep into the science of Shaken Baby Syndrome and learns that they have the nastiest lobbyists in the world. These people make sure that every person who gets accused of this spends the rest of their life in prison. Conlon’s also been dealt a bad defendant, as Kristian is big and emotionless. He’s immediately compared to Lennie Small from In Mice and Men.

As we race towards the court case, Conlon finds out that the whole Shaken Baby world is a lie. That the science doesn’t hold water. In fact (spoiler), he learns that the medical community and legal community know this but that they’ve convicted so many people of it by this point that there’s no going back. They have to keep reinforcing the lie. Luckily, Conlon puts enough fear into the establishment that Kristian is inevitably let go.

There are a couple of approaches you can take to a story like this. You can create doubt about the suspect and then take your reader on a roller-coaster ride where sometimes you make the suspect look innocent and sometimes you make them look guilty, and the reader is constantly trying to solve that puzzle.

This is the approach they take in docs (or series) like The Staircase. At first we think the husband definitely did it. Then, when we hear him talk, he doesn’t sound like he did it at all. Then, a little later, we learn that he was having affairs. Now we think he did it again. But then we’re told that the wife knew about the affairs. Then we hear another woman he knew died from a staircase fall and we’re back on the “guilty” train again. These can be fun when executed well.

The other approach you can take is the one they took in this script. Which is that the father is clearly innocent but everyone in the world thinks he’s a child-killer and they’re determined to make sure he’s convicted as so. This creates an enormous amount of sympathy from the reader because nobody wants to see something bad happen to someone who’s clearly innocent. Even less so if everyone wants to take him down in bad faith.

For that reason, the script worked for me, which I was surprised by. I mean, yes, I still think a script like this is a losing proposition cause it’s so depressing. But I was into the stuff where they’re trying to take down Kristian. I wanted him to overcome their full-force attack.

Which is a perfect segue into today’s dialogue lesson. The following scene is a long one. But it’s also a great example of how you can write good dialogue without being a wordsmith. If you’re good at setting up the right scenario, the scenario will do the work for you. I think most of you could write this scene yourselves if it was set up for you. Whereas, with a Tarantino scene, maybe .001% of you could write something similar. In other words dialogue scenes like this are within reach.

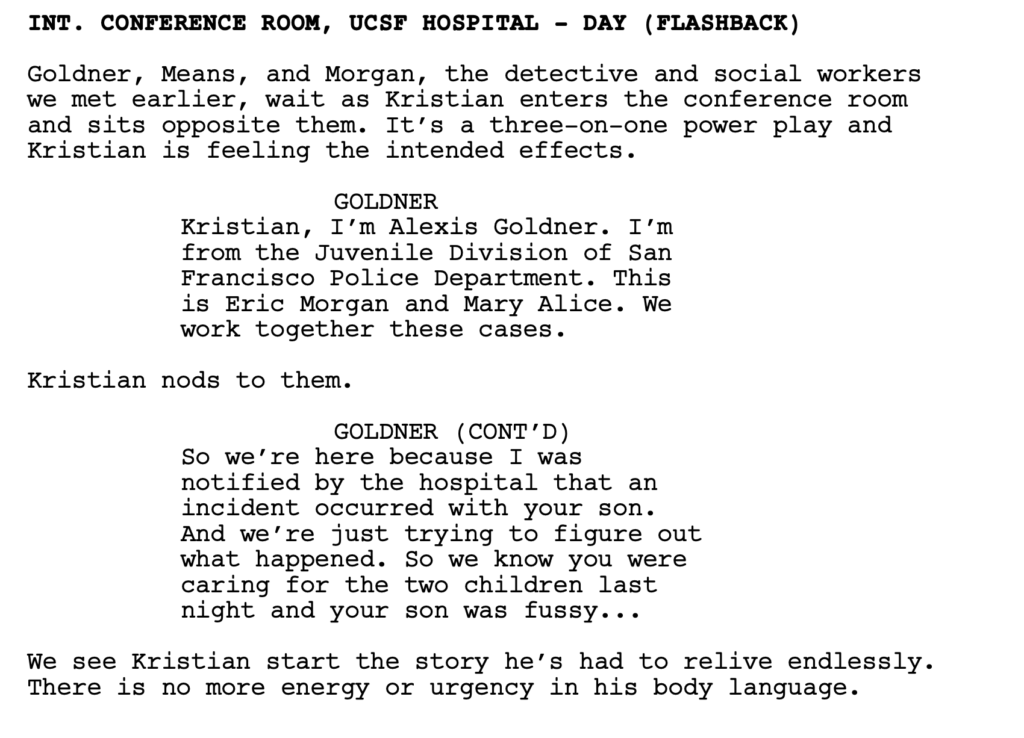

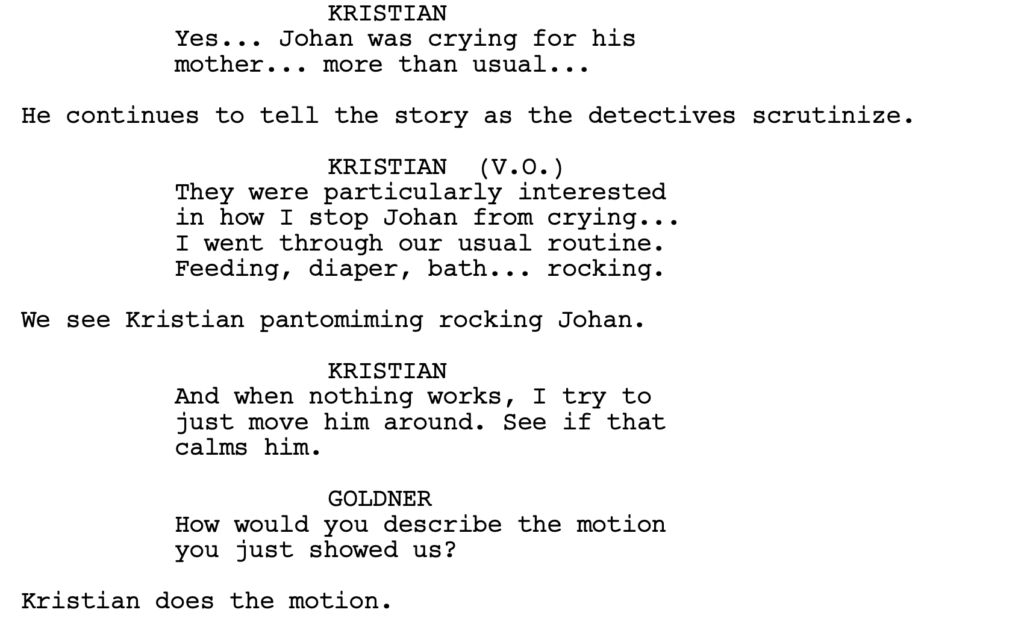

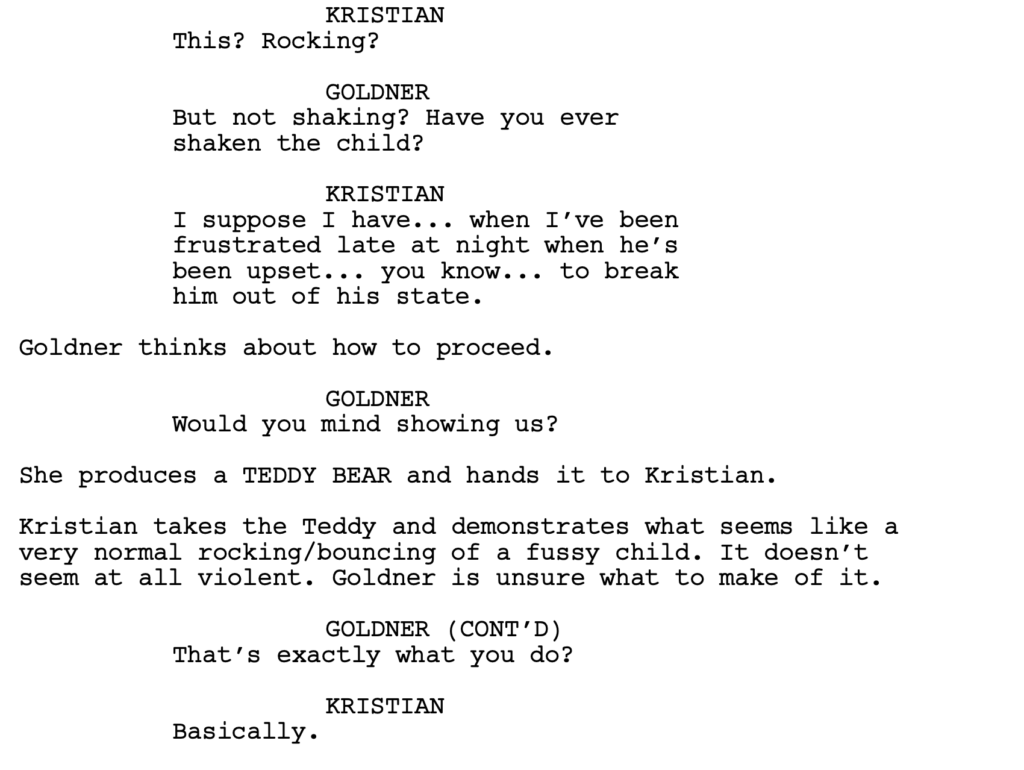

The scene takes place with Kristian being brought in to see Child Services not long after he and his comatose child arrive at the hospital.

You want to note a couple of key things here. One, the child services characters have the goal in the scene. It’s to find out what led to the kid’s injury. However, here’s where our nifty dialogue lesson comes into play. The child services people are framing the conversation as if that’s the goal. But what they’re really trying to do is get Kristian to admit he killed his kid.

Dialogue always plays better when there’s something going on on the surface, as well as something that’s going on underneath the surface, which is clearly happening here.

Also, note the extremely high stakes of the scene. If Kristian screws up and says the wrong thing, he doesn’t get a pass. That thing very well could be the smoking gun the prosecution uses to convict him of murder in court. Dialogue is electric when the stakes are high.

Another thing is that the child services people are being disingenuous. They’re trying to trick him – pretending they’re on his side when they’re the exact opposite. What this does is it makes the reader protective of Kristian. We feel like he’s being misled, so we become his ally in the scene. We’re rooting for him to survive.

Finally, note the conflict. Almost every good dialogue scene has some level of conflict in it. And what creates more conflict than one side trying to ruin a guy’s life and the other side hanging on for dear life?

By the way, the reason this doesn’t have to be Tarantino-type dialogue is because the content of the scene is so strong. There are real consequences to this moment. And when that’s the case, you don’t need to prove your verbal jousting skills. Those will actually make the scene worse.

Once you’re able to consistently write a scene like this, you’re going to be okay dialogue-wise. Cause these scenes can really carry a script. Just note that a lot of the work here was done before the scene, not in the scene. Once the scene is set up, the dialogue writes itself.

I’m still not thrilled that the overall feeling I get from this script is one of depression. I like to either feel good at the end of a script or, at the very least, I want it to make me think. With that said, the script surprised me by how much it pulled me in. So I think it’s worth checking out.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: It helps in these scripts when the case is about something bigger than just winning the case. While False Truth isn’t making a point about racism or anything gigantic like that, it is about the fact that these “shaking baby” cases are bogus and that evil overly-emotional people have been using their influence to convict a lot of innocent people through pseudo-science. So we do get the sense that the court victory has a bigger effect on the world.