Genre: Comedy/Period

Premise: A 1950s Hollywood fixer finds himself on his first job he can’t fix – the star of the studio’s biggest movie ever is kidnapped by a group of communists.

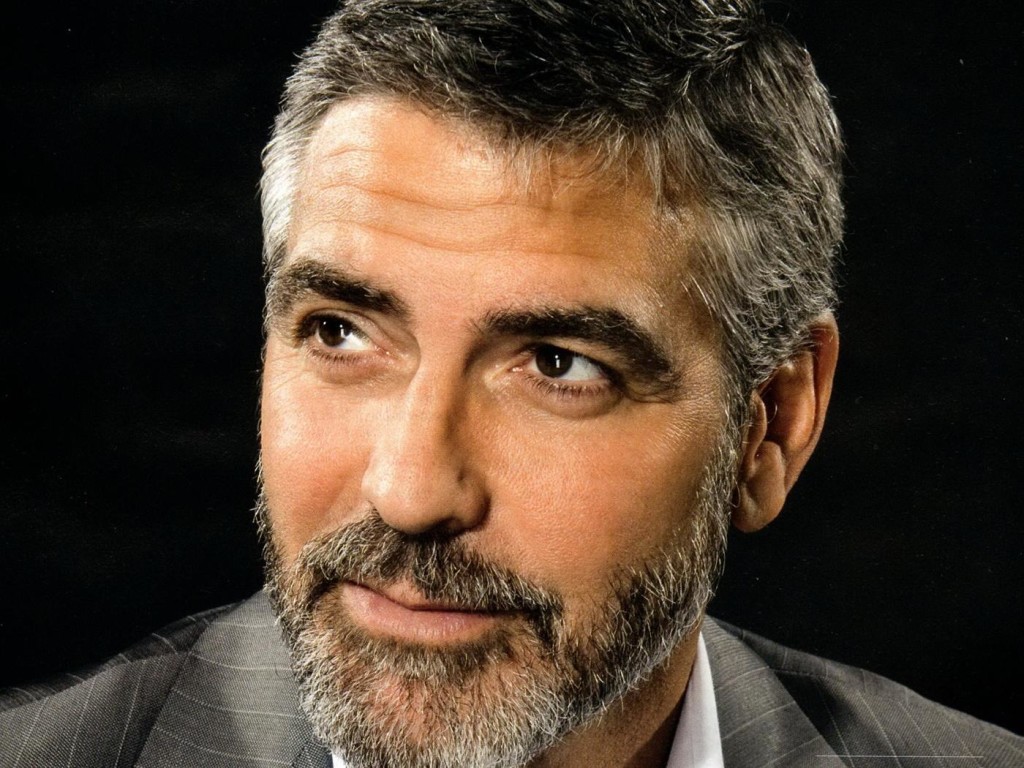

About: This is the Coens’ next movie. As you’d expect, actors are lining up in the hopes that the brilliant character-building brothers can put them in a position to win an Oscar. So this film is stacked. It will star Scarlett Johansson, Channing Tatum, Josh Brolin, Jonah Hill, Tilda Swinton (who it should be required is in every weird movie from here on out until the end of time) and, of course, George Clooney.

Writer: Joel & Ethan Coen

Details: 111 pages

There’s this rumor going around that I don’t like any movies/screenplays that don’t fall under the traditional safe Hollywood paradigm. This rumor started because I hated scripts and movies such as Upstream Color, Inside Llewyn Davis, Somewhere, and Winter’s Bone.

But it’s simply not true. I like plenty of indie movies. I enjoyed Blue is The Warmest Color, Silver Linings Playbook, Black Swan, Rushmore. What I don’t like is bad storytelling. And because indie film is a place where filmmakers take more chances, the results typically play at the ends of the spectrum, which leads to extreme reactions. So when I don’t like something, I really don’t like it. Inside Llweyn Davis still leaves a bad taste in my mouth. I mean you had the biggest asshole main character of the past decade in a movie without a plot.

And that’s what I don’t get. The Coens are always at their best when they’ve got a good plot going. The Big Lebowski, No Country, and Fargo all had big plots thrusting the story forward. Inside Llewyn Davis had… a lost cat. That was the plot.

And you know what? I don’t even require a plot to like a movie. I need a plot OR great characters. Just one of the two. Like Swingers. Swingers didn’t have a plot. But the movie had great characters, so you enjoyed the ride.

Which leads us to today’s script, the Coens’ latest. And I can start off with some good news. This one actually has a plot. Is that plot any good? Well, let’s take a trip into the Coen Brain Collective (bring any drugs you can locate within the next 10 seconds) to find out.

Eddie Mannix is a fixer. Hollywood in the 1950s is a lot like Hollywood today, with one major difference – it was easier to control the image of its stars. Which was important. Because studios used to OWN stars back then. There wasn’t any of this “free agency” shit. A studio had you under contract. So if you drank a lot, got arrested a lot, were gay, backed up your files on icloud – it was in their best interest to keep that information out of the papers. And that’s where Eddie Mannix came in. He was the master at getting rid of these problems.

Until this movie of course, when something goes horribly wrong. Mannix’s studio loses the star of its latest Ben-Hur-like film, “Hail, Caesar!” Baird Whitlock is yanked off the set by a bunch of commies, which was a really bad thing to be back in 1951 in Hollywood. These Commies, who happen to be screenwriters, are pissed! They’ve been writing all these movies for Hollywood, but other writers are getting the credit (hey, how is that any different from today?). So they do the obvious thing to enact revenge – they kidnap Baird and demand 100 thousand dollars from the studio (which I’m assuming was a lot of money in 1951).

As word starts to leak out that Baird may have been kidnapped, Mannix must work the phones to keep all the gossip columnists from publishing the story in tomorrow’s paper and ruining his studio’s investment forever. This little event also threatens to rekindle an old rumor of Baird’s that has plagued him since he first got into the business. We’re talking about the “On Wings as Eagles” rumor, which is something so big, so dark, that even Richard Gere would find it disturbing. Mannix has certainly got his work cut out for him. Can he save the day one last time? We shall see!

Let’s start out with the good. This is a lot better than Inside Llweyn Davis. It’s actually fun. In fact, it’s closest in tone to the Coens’ Big Lebowski. Unfortunately, it doesn’t have the same super memorable characters as Lebowski. Eddie Mannix is a wild-eyed work-hound, but I’m not sure I know anything about him beyond that.

Traditionally, we get to know the main character in a screenplay, understand the flaw holding him back, empathize with him, sympathize with him, hope that he changes, and that’s really why we go along for the ride. We’re rooting for this person to become better and succeed.

The Coens’, as you know, don’t always subscribe to this approach. Their characters have great big flaws, but those flaws aren’t always figured out. Look at The Dude in The Big Lebowski. His flaw is obvious. He’s a lazy irresponsible bum. He has no initiative and does nothing in life. In a normal movie, we’d watch as The Dude realized this, and eventually learned to take initiative.

Instead, The Dude keeps on being The Dude at the end. He’s The Dude. Nothing’s going to change about him. The question is, why does this work when every screenwriting book in the world tells you your main character has to have a flaw and that, over the course of the movie, they must overcome that flaw? It works because The Dude is also one of the most lovable characters ever created. Which means, purposefully or not, the Coens’ are drawing on one of the oldest screenwriting tricks in the business. They made their main character super-likable. And sometimes that’s enough.

Conversely, this is why, I believe, Inside Llewyn Davis didn’t catch fire with the public. The main character was a huge dick. Maybe this would’ve worked had Llewyn showed growth. Audiences have proven with movies like Groundhog Day that they’re willing to watch a dick if he shows signs of improving. But Llewyn never did.

If you’re going to give us an asshole character AND they’re going to remain an asshole character throughout the movie, fuggetaboutit. I mean the Coens are so amazing at creating secondary characters that they can keep their movies at least watchable (John Goodman and Justin Timberlake were great in Llewyn Davis), but in the end, it’s that protagonist who’s either going to lead you to the promised land or not.

Which brings us back to Hail Caesar. Eddie Mannix was so busy running around saving everybody else’s ass that I never got to know him. So I never really cared. And the more I thought about it, the more I realized the Coens missed a major opportunity in connecting us and making us care about Eddie. Eddie didn’t have a major relationship in the film. He never had a girl he liked, a family member he wasn’t getting along with, an important friendship or work relationship. He didn’t have that one thing that got us into his head. Again, look at The Dude. He had Walter (John Goodman). That was the entryway into The Dude’s mind so we could get to know him. That wasn’t here with Eddie. And it really hurt the screenplay. I mean how many screenplays survive when you don’t feel like you know the main character afterwards?

So despite having a few fun moments, Hail Caesar was a bit like a runaway chariot race. It eventually went scurrying off the tracks.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The hero’s key relationship in the story (girl, family member, friend) is one of the easiest ways to get the audience into the hero’s head. It’s through dialogue with these characters that we get to see your hero’s problems, his worldview, his flaws, his fears, his dreams, his insecurities – all the things that make him him. If your main character doesn’t have anyone to talk to, it’s going to be really hard for us to connect with him.

What I learned 2: Frack for drama! Never forget the importance of stakes for your main character. If there aren’t major consequences for your hero failing, you’re only mining a fraction of the drama you could be in your movie. The Coens, who are usually pretty good with stakes, had none here for Eddie (another problem with his character). I didn’t get the sense that he would be in any trouble if he didn’t find Baird. We needed that scene where the big scary mobster-like studio head took Eddie aside and said, “This is our biggest movie ever. I don’t want it to bomb because you didn’t do your job. You know what happens to people who don’t do their job, right Eddie?” And that’s all we needed.