Genre: True Story

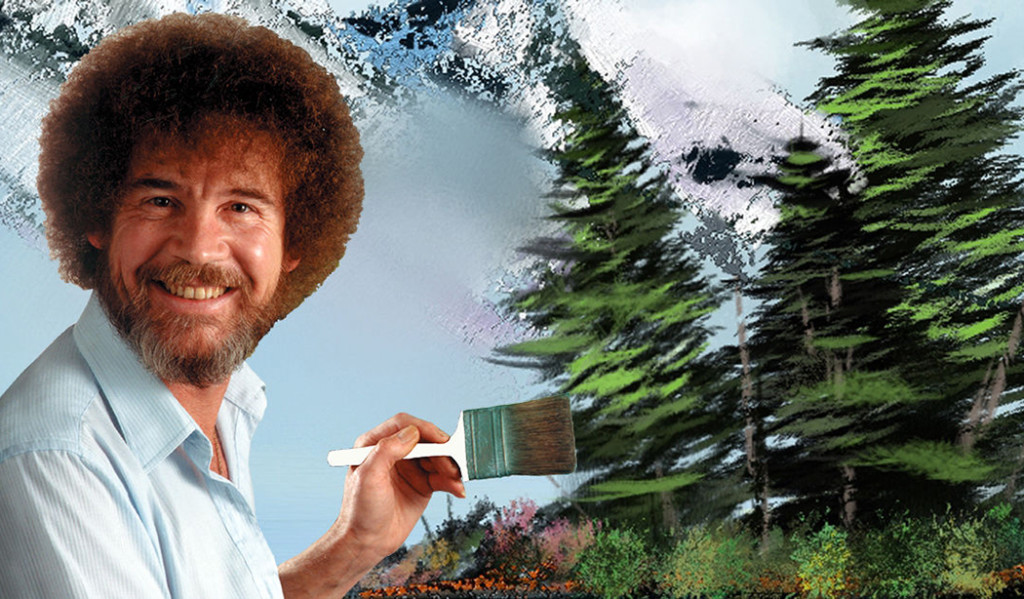

Premise: After Bill Alexander’s long-running show “The Magic of Oil Painting” was cancelled by PBS and replaced with Bob Ross’ show, “The Joy of Oil Painting,” Alexander accuses the soft-spoken afro’d Ross of stealing his act, inciting a bitter dispute that changed the lives of both men forever. Based on a true story.

About: This script made the Black List last year with 10 votes. Shawn Dwyer

is just starting to make a name for himself. He had another script, 73 Seconds, pitched as “Hidden Figures” meets “Spotlight” that got a producer attached. However, this script hasn’t yet secured a buyer.

Writer: Shawn Dwyer

Details: 112 pages

It’s fun reading these Black List scripts that are still searching for buyers because you can evaluate what it is about the script that gets one side of the industry excited but not the other. And this goes both ways. There will be specs that sell for a lot of money that don’t make the Black List. It happens all the time. The fact that this hasn’t sold implies that the subject matter is too obscure. Bob Ross is a cult hero. But he’s not necessarily a household name. I liked the concept here. The idea of two people sparring in an arena as peaceful as painting has a nice ironic ring to it. Let’s see if it’s any good.

We start in Prussia. 1927. Some boys, including our hero, Bill, are playing around in the forest when they find the remains of some old World War 1 equipment. In the midst of them joking around, one boy finds a grenade, prepares to throw it, only to have it blow up in his hand, instantly killing him.

Cut to 1982 and Bill, now 60 years old, is doing a landscape painting on PBS. In the middle of the painting, Bill stares off into nothing, only to snap out of it 60 seconds later. Apparently, this sort of thing has been happening a lot lately because a PBS suit sits him down to tell him he’s being replaced by an up-an-coming painter named Bob Ross. If it’s any consolation, they tell Bill, Ross used to be a student of his.

Determined to keep his gig, Bill meets Ross to give him the business. But Ross is just so chill, man. And after talking to him, Bill okays the transition, but on one condition. Ross will use Bill’s paint and hawk it on the program. That way, Bill still has an income source. After a few more flashbacks to Prussia, each one meant to convey how evil Bill’s father was, Bill learns that Ross isn’t living up to his end of the deal. In fact, he’s stolen Bill’s special paint mixture and called it his own!

This gives Bill an idea. He’ll sue Ross off the air! Bill’s lawyer says that if they can prove that Ross’s paints are replicas of his own, they’ll win the case. So Bill goes out and visits the totally chill Ross at his house, pretending to shoot a video with him so he can steal his paint. He barely gets a pale out of there and gets it tested. Indeed, it’s a replica of his paint. But by that point, it doesn’t matter. Bob Ross has become a superstar and there’s nothing Bill can do about it. Oh yeah, cut to 20 years later and Bob Ross dies of cancer.

Ooph.

Okay.

Whoa.

Um.

Not gonna lie. This was a rough read. I thought I was getting a comedy. But I guess this was a straight drama with the occasional flitter of humor (usually from Ross)?

There’s a lot wrong with this spec. A lot of mistakes young screenwriters can learn from.

For starters, there was a lot of repetition. After Bill gets fired, he and his wife seemingly have 50 conversations about what they should do next. Very little was happening in this section or the rest of the story, for that matter. Where’s the plot?

Plot can be described as a series of developments that evolve a story into something different from what it has been so far. The severity of the development will determine how radically the plot has changed. A basic example is a car driving on a freeway. Theoretically, we could follow that car for 90 minutes and call it a movie. In that case, there would be ZERO plot development and the movie would be boring.

However, let’s say the car blows a tire. Now we have a development. They have to pull over and figure out what to do about the flat tire. It’s not a severe plot development. But it does change the direction of the story slightly. Or let’s say we’re in the car, husband and wife are chatting. And, out of nowhere, the wife pulls a gun out and shoots her husband in the head. This would be a SEVERE plot development, right? It will have radically changed the direction of the story.

Yesterday, we had a writer who understood plot development. He knew that the story needed to change direction consistently, and sometimes radically. “Happy Little Trees” is the opposite of that. So little happens in this story that each time I had to turn the page it felt like I was lifting the heaviest barbell at the gym. After 20, 30, 40 pages of nothing happening, I knew each page was going to be a replica of the previous one.

After Bill gets fired, the next plot development – him wanting to sue Bob Ross for stealing his paint mixture – doesn’t happen for 60 pages. In the meantime, we’re getting scene after scene of Bill and his wife trying to figure out what to do. It’s simply not enough plot.

It’s not impossible to write good movies that are lightly plotted. But in order to do so, we really have to like the characters. Eighth Grade is a good example of a lightly plotted movie that still works because we empathize with the main character so much. I couldn’t find any reason to like Bill. He was negative. He complained a lot. He was whiny. I think the writer made the mistake of assuming that just because Bill’s job was taken away, we’d sympathize with and root for him.

But it doesn’t work like that. You still have to create a personality that we like on some level. Bill doesn’t have a single quality to him that allows that to happen. And it doesn’t help that Bob Ross is so likable. Sometimes what you can do in these movies is make the other guy a con man. So you’d have Bob Ross hypnotize the world, but when he’s alone with Bill, he’s a terrible person. We would then root for Bill to expose Bob. But Bob Ross is both good in public and good in private. So we don’t even want Bill to beat him.

I’m sorry but I have no idea why a writer would think we’d root for this person. It’s baffling to me, to be quite honest.

On top of that, there were tonal issues. The present day stuff has a light harmless feel to it, yet the flashbacks are brutally violent and uncomfortable for some reason. It was like two different movies. It only added to the struggle of keeping the pages turning.

There was a movie in here somewhere. Had the conflict between Bob and Bill been more intense, it would’ve at least given the screenplay some life. But between all the problems I mentioned and just an overall, way too relaxed, feel, I couldn’t get into this.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Does your concept work better as a comedy? Sometimes we get blinders on when we come up with an idea. With some objectivity, you might find that the idea you’re taking so seriously actually works better as a comedy. This needed to be a comedy all the way. This is not a serious movie by any stretch of the imagination. Embrace the comedy. Make the characters more ridiculous. And have fun with it. This needed a fun touch.