Genre: Drama/Biopic

Premise: A married news columnist who’s checked out of life finds his way back into it when he does a story on Mister Rogers.

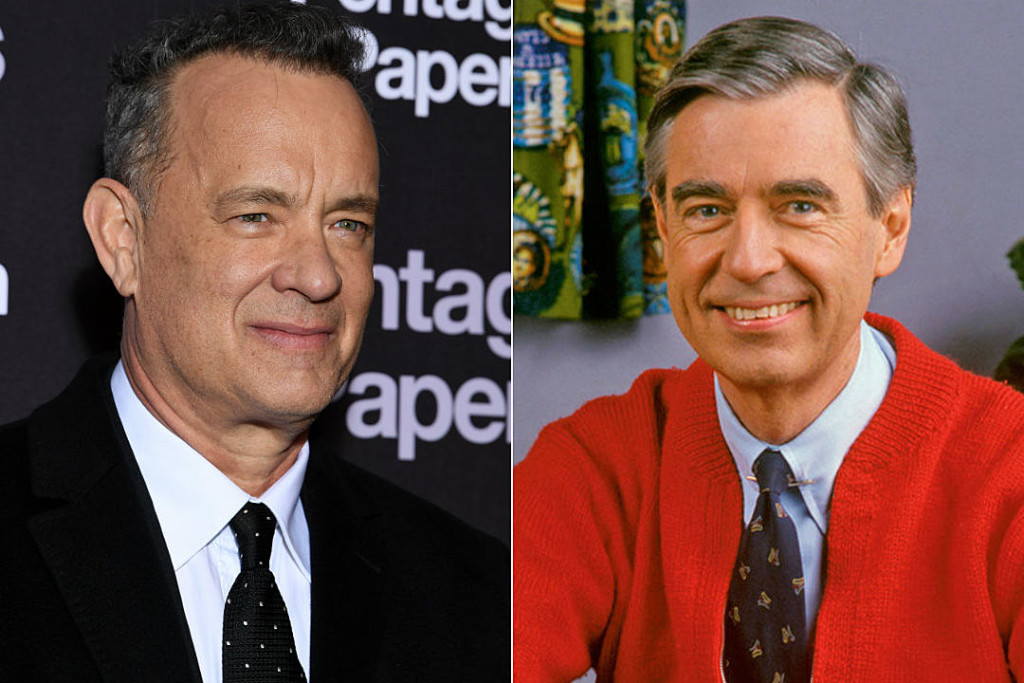

About: Originally, this script made a prior Black List, I believe in 2012. Then last year it became a super-hot property, attaching Tom Hanks to play Mister Rogers. The writers, Micha Fitzerman-Blue and Noah Harpster, have used that momentum to secure a gig on one of next year’s big releases, Malificent 2. The two made their way up the ranks by writing on Amazon’s award-winning show, Transparent.

Writer: Micha Fitzerman-Blue & Noah Harpster (based on Tim Madigan’s memoir)

Details: 111 pages

I’ve avoided this script for so long. No matter how you presented it to me, there was no way I could conceive of a Mister Rogers movie being good. The character screams “boring subject matter.” And yet the project has received a ton of buzz. It didn’t make sense. Finally, my curiosity got the best of me. I am about to read a script about Mister Rogers. Wow. I hope I don’t fall asleep.

37 year old Tim Madigan has the perfect life. He just doesn’t know it. He has a beautiful caring wife in Catherine and a wonderful 3 year old son, Patrick. But he hates his life. He sleeps in a separate bed from Catherine. He avoids spending time with Patrick. Often times, he’ll come home after a long day of work and, as he’s about to pull into his driveway, keep driving and go to, of all places, Cracker Barrel. You know when you’re picking Cracker Barrel over anything it’s bad.

Tim works as a journalist, and because the film takes place right after the Columbine shootings, his boss wants him to write a story about what programs the shooters watched when they were children as a way to explore the connection between TV and violence. Ironically enough, one of the shows the kids watched was Mister Rogers. So Tim begrudgingly calls Mister Rogers to interview him.

When Tim visits the set in nearby Pittsburgh, the first thing he sees is Mister Rogers talking to a sick boy, trying to cheer him up. He looks around for the cameras, figuring this must be some Make-A-Wish Foundation deal, but is shocked to find that Mr. Rogers is doing this because he’s… well… a good guy. “He does this every day,” an A.D. tells Tim.

During lunch break, he attempts to get his quick and dirty interview in and then get the hell out of here, but is confused when Mr. Rogers starts asking him about his personal life and is genuinely concerned. When Tim gets home later, he starts looking up old Mr. Rogers interviews and becomes a bit infatuated with him.

Still, Tim is ready to move on from Mr. Rogers until, out of nowhere, his wife tells him he needs to leave. It’s not just that he’s mentally checked out on the marriage. It’s about Patrick, how he’s not at all a part of his son’s life. Devastated and confused, Tim moves into a hotel room, where he soon finds himself calling Mr. Rogers for advice. Slowly but surely, Tim sees what makes this man so amazing. He cares about people. And, more importantly, he cares about himself. He’s a friend to himself, something Tim has no context for.

Taking Mr. Rogers’ advice, Tim begins to work on connecting with people, starting with his co-workers. From there, he attempts to rekindle his relationship with his sick brother, whose business he ran out on years ago. The experience shows Tim what it means to be connected with others, which allows him to save his marriage. As the titles tell us at the end, Tim and Catherine are still married today and are the happiest couple they know.

The operating thesis when you write biopics about sugary sweet famous people is that you have to show their dark side. Expose to the world that they were battling a heroin habit or were terribly depressed. The reason you do this is to create contrast within the character. Because if the character is as friendly or amazing or honest as they presented themselves to the world… how interesting is that?

Over the years, I’ve grown tired of this approach. Partly because you know it’s coming. But also because it’s depressing. Sometimes you don’t want to look under the hood to see that the engine is fried. And it’s a big reason why biopics are broken. How many ways can we go inside a person’s life to find that while they were hugely successful they were also terribly miserable?

I didn’t think there was any way around that until today. These writers figured out a nifty loophole to the problem. What if you kept that famous figure just as sugary sweet as they’ve always been and shifted the fried engine over to a second character?

It’s genius, isn’t it? Mr. Rogers remains awesome in our heads. But we still get the conflict and obstacles and difficult journey that every story needs in order to be entertaining.

Everybody who’s considering a biopic should consider this approach. I’m not saying you should do it for sure. Every subject needs to be considered via its own strengths and weaknesses and then you pick the story that best accentuates the strengths. But with this genre getting so stale, you need to reinvent it if it’s going to stay interesting.

One of the reasons this story works so well is because the writers walk that line between Tim being a “bad” person but still getting us to root for him. Because when we meet Tim, he’s racing away from his wife. He won’t spend five minutes with his son. He ignores his coworkers. Let’s face it. He’s a selfish dick.

While some writers attempt to balance this out by writing a cliche “save the cat” scene, Fitzeraman-Blue and Harpster try something different.

There’s a moment early on where Tim is watching Mister Rogers do a segment for his show with puppets. And in the segment, a tiger puppet is asking another character if he, the tiger, is a “mistake.” And the other character is explaining to him that he’s not. But clearly Tim starts to see some of himself in that tiger and he breaks down. In that moment, we realize that Tim doesn’t want to be this way. He doesn’t want to be a jerk to his family. He just is. And he needs to learn how to change.

Once we know Tim wants to change, we root for him, regardless of what he’s done in the past. Had Tim been a jerk to his family and he doesn’t give a shit if he ever changes or not, there’s no way we’re rooting for him. That was a really clever solution by these writers to an age-old screenwriting problem.

My only issue with the script is that the narrative is sloppy. Mister Rogers is over in Pittsburgh, which is fine if you’re writing a memoir. Phone calls will do the job. But in a movie, we need to see people. We need to be around them for the most impact. So there’s a lot of driving back and forth to Pittsburgh that messes with the pacing.

On top of that, Tim’s brother’s sickness isn’t woven into the first half of the story enough. As a result, when it becomes the primary storyline in the last 40 pages, it takes us awhile to adjust. And, again, it’s because everyone is so far away from each other. Tim’s in one city. Mr. Rodgers is in another. Tim’s brother is in a third city. It was Iike Avengers-level exposition needed to keep track of all these places.

This is why most screenplay-friendly stories take place in one area with one set of characters that are easily accessible. So you don’t need to spend 25% off your script muscling through the exposition required to keep the story clear.

Despite that, this was a really enjoyable read. Is it a little too sweet in places? Sure. But come on. We’re talking about Mr. Rogers here. If you can’t feel good after a movie about Mr. Rogers, when can you?

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I want to make it clear that I loved this script. But this lesson is still relevant for amateur screenwriters – When considering a script, you should consider the amount of exposition that will be required to tell the story. If you have a lot of characters moving around to a lot of different places (like Avengers or here), you’re going to need a lot of scenes that remind the audience where we are and explain to them why we’re going to the next place. There are things you can do to make these exposition-heavy scenes more palatable, but sometimes the best solution is to write a simpler “spec-friendly” story where you don’t have to worry about exposition in the first place.