Today’s writer makes one of the snazziest minor innovations to the screenwriting format I’ve seen since I started reading. This needs to become a mainstay in all scripts going forward!

Genre: Western/Thriller

Premise: When a poor but ambitious family man finds a barrel of gold, he attempts to follow his dreams without allowing his greed to drive him insane.

About: This script finished in the middle of the pack on last year’s Black List. These days, many Black List scripts come already optioned or purchased, or, at the very least, campaigned for. Let the Evil Go West is one of the few scripts that made the list bare naked. That implies that it was passed around due to the quality of the script alone – a rarity. Screenwriter Carlos Rios is an alumni of Universal’s Emerging Writer’s Fellowship, which is becoming a hotbed for finding strong emerging talent.

Writer: Carlos Rios

Details: 117 pages

One of the things you become keen on when you read a lot of scripts is knowing when you’re reading a writer and when you’re reading a pretender. The pretender is like the annoying guy at the party. He’s got nothing of substance going on so the only way to get your attention is to yell and scream and jump in the pool several times.

On the flip side, good writers are like Andy Warhol. They’re so confident in themselves that they’ll stand in one place, barely say a word, and let the party come to them.

Let The Evil Go West is one of the coolest written scripts of 2016. I LOVE this guy’s style. First off, he grounds that style in the format’s most dependable approach – SIMPLICITY. His writing is descriptive, but always stays on point, rarely eclipsing 3 lines.

On top of that, he uses a “continuous style.” A continuous style continues sentences and paragraphs even after a line break, sometimes bypassing capitalization in order to keep your eyes moving.

It’s a best of both worlds scenario. The only benefit of “wall of text” writing is that the sentences visually connect one after another so it feels like one continuous thought. The problem with walls of text is that they’re daunting and readers feel overwhelmed by them.

With a continuous writing style, we jump down to a new paragraph, and yet we’re still within the same thought, action, or description. However, we don’t have to deal with the cumbersome mass of text that usually accompanies that kind of connective writing.

Rios is a such a snazzy writer, he even innovated the format. More on that in a second. But first, let’s learn what this script is about.

30-something Abner Ellis is a lot like Daniel Plainview from There Will Be Blood. He’s an ambitious man who wants to take advantage of a country that’s still in its infancy. He’s got a beautiful wife, Elspeth, and a handsome little boy, Benjamin, who he plans to bring along on this journey.

The problem is, Abner is poor as shit. And back then, the only way to make money was to have money (actually, that hasn’t changed). Unfortunately, Abner’s been stuck in a string of low-paying jobs that eventually brings him to the Trans-Continental railroad.

While working for 2 dollars a day clearing land, Abner lucks out when he finds a barrel of gold in the nearby forest. Sure, there are four dead men laying by it, all of whom killed each other over the stash. But that’s the last thing on Abner’s mind. He’s finally in the game.

Abner moves his family up to Wyoming where he puts his grand plan into motion. Abner will build an entire town that the brand new railroad will run through. Elsbeth isn’t so sure, but Abner’s dogged determination to make something of his life eventually convinces her.

There’s one problem. Abner’s losing it. He’s so obsessed with his barrel of gold and so convinced that the next guy is around the corner, plotting to steal it, that he becomes more protective of it than he does his own family. And when real threats do surface, he’ll do anything to keep his gold. Even if it means killing those closest to him.

You’re dying to know what that innovation is, right? Okay, let’s do it.

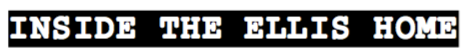

One of the annoying things about reading is the inefficient syntax that delineates DAY from NIGHT at the end of a slugline. Most of the time, readers shoot past slugs to get to the important stuff, and often become confused as a result, needing to back up and check what the slug said to gain context. DAY and NIGHT are just one casualty of this glitch.

So Rios REVERSE BLOCKS his nighttime slugs. This way, we get an instantaneous VISUAL CUE that it’s night time. It’s genius! This was the first script I’ve read where I instantly knew whether it was night or day without having to read anything.

Now if someone could invent a visual slug that also delineated EXTERIOR and INTERIOR we could streamline screenwriting forever and push these janky math-like documents one step closer to a natural storytelling medium.

Well that’s great, Script Nerd Carson. But what about the script?

The script was great. There were so many hallmarks of good storytelling here.

Start with Abner. Scripts work better when the main character has a strong drive. Not only do we like people who are driven more than those who aren’t, but driven characters create a natural reason for us to keep reading. We want to see if the character is going to achieve what they’re driven to do.

Abner wants nothing more than to become great. So we want to see if he can do it.

Contrast that with a character who’s fine with where he is in life. Maybe something terrible happens to him and that’s what begins his story. You can still write a good script this way, but the story’s always going to be more powerful and the main character more likable when it’s HIM WANTING SOMETHING that drives the story as opposed to the story driving him.

But what really placed this script above so many others was the VARIETY IN STORYTELLING. What this means is that when you write a movie like Taken or Bourne, there’s only one beat being repeated throughout the movie – CHARGE THROUGH OBSTACLES TO CONQUER THE GOAL (“take down the CIA” in Bourne, “find my daughter” in Taken).

That can get tiring if every section is like that. Sometimes what intermediate writers will do to alleviate this is write a slow “sit-down-and-talk” scene. But all that does is momentarily alter the pacing. It doesn’t add VARIETY to the way the story is being told.

Variety in storytelling means creating entire sections that have a different purpose and feel than other sections. When you do this right it’s like magic because it keeps the reader off-balance and unable to tell where the story is going.

For example, early on we have a section where Abner goes off to make money on the railroad. It’s a goal-oriented sequence – get a job to support my family. However, when Abner brings the gold home, that section is entirely different. It has no goal. Instead, Rios builds a sense of fear surrounding the gold – that someone may have followed Abner and is planning to kill the family and take the gold.

So even though we’re sitting in one location for 15 pages, we have something that’s driving our interest – a potential threat from outside. And that fear permeates every scene. More importantly to my point, IT FEELS COMPLETELY DIFFERENT FROM THE RAILROAD SECTION.

So that’s something to keep in mind – that you’re not hitting the same story beat over and over again every sequence. Granted, it’s easier to do this when the timeline is extended, like it is here, but crafty writers can achieve this in time-crunched narratives as well.

The only reservation I have about the script is that the ending gets really dark. The whole movie was such a rush and then we’re hit with this hard-to-take finale. I guess it was inevitable but still tough to swallow. However, if you liked There Will Be Blood and The Shining, you’re going to go fucking go apeshit over this.

What a script!

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: There’s no need to draw attention to jumps in time (writing down: “6 months later”). Remember that time jumps can kill plot momentum. We’re zipping along and then we see: “1 Year Later.” We feel the wind sucked out of the plot. We’ve got to start building momentum all over again. For that reason, only notate time jumps if it’s necessary for clarity. Otherwise, do what Rios does here and use visual cues to show we’ve jumped forward. For example, we’re on an empty strip of land that Abner’s just purchased for his town, than we cut to an almost completed train station and we just seamlessly keep moving through the story.