One of the more controversial new screenwriters on the scene comes at us with yet another one of his high concept ideas

Genre: Drama/Thriller

Premise: (from Black List) When her domineering director makes her film the same scene 148 times on the final night of an exhausting shoot, actress Annie Long must fight to keep her own sanity as she tries to decipher what is real, and what is part of his twisted game.

About: Screenwriter Collin Bannon routinely makes the Black List. He’s done it again here, as this script finished with 12 votes on last year’s list, the unofficial compilation of the “best screenplays in Hollywood.”

Writer: Collin Bannon

Details: 109 pages

Scarjo for Annie?

Scarjo for Annie?

All right, now that we’ve got all of that conflict out, let’s take things down a notch and review a screenplay about going crazy!

I remember reading these stories about Stanley Kubrick forcing Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman to do a million takes on Eyes Wide Shut and how Kidman, in particular, almost went insane.

Then later, probably because he was inspired by Kubrick, David Fincher did the same thing to his actors. I remember Edward Norton being particularly thrown by the first scene he shot for Fight Club. Norton thought he did a pretty good job on take one. But Fincher ended up making him do 20 more. And not just doing the takes, but not giving any direction. I got the feeling from Norton that it was a bit of a mind f—k.

I think the idea of tons of takes is to strip the acting away from the actors. And just have them “be.” I’m not convinced it works. I guess if a scene requires you to look emotionally spent it might work. But it’s hard to give when you’ve been told you’ve failed 27 times in a row.

So I thought building a movie around this concept was cool. It’s also a unique way into a loop narrative. Whenever you can exploit a trend in a way that doesn’t feel like the trend, I always give writers props for that.

It’s 1981 and we’re filming an elevated horror movie (Think The Exorcist, not Friday the 13th) in the middle of some eastern European country. At the start of the script, Annie, our hero, is at her wit’s end. They’ve filmed the entire incredibly intense movie. There’s only one scene left. And Annie is desperate to finish so she can get home for her cancer-stricken mother’s surgery.

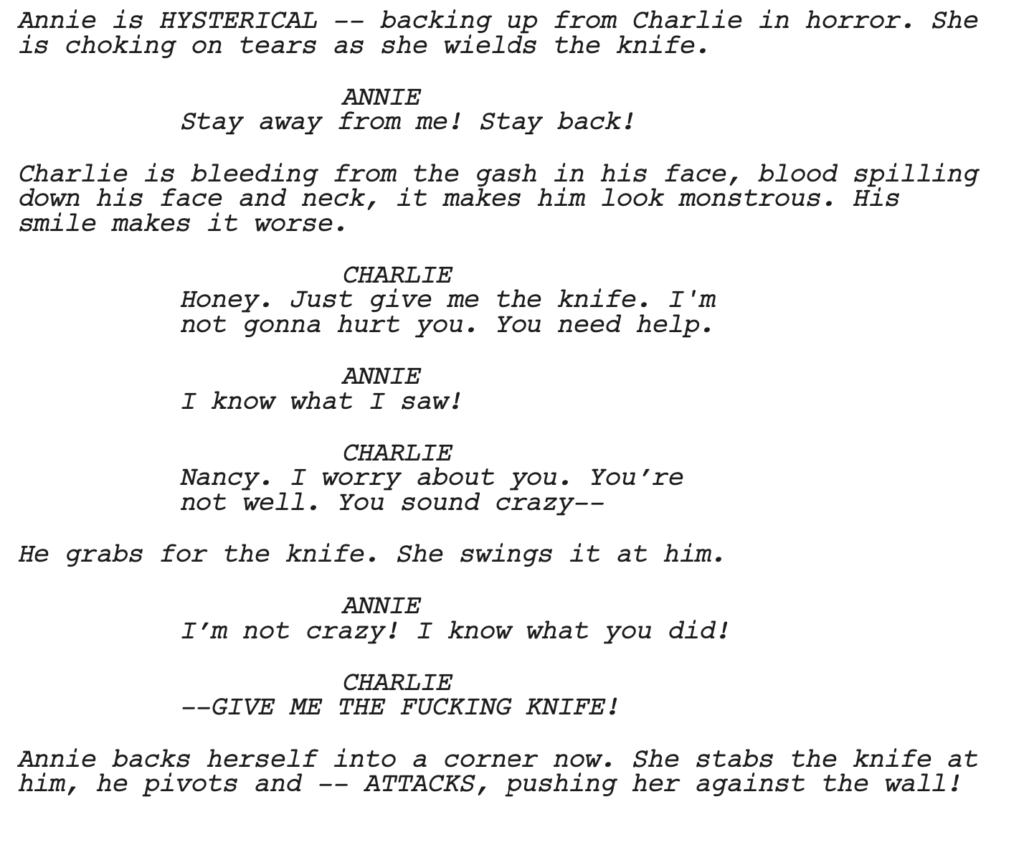

There’s one man in the way, though. Howard Bloch. I could get detailed about who Bloch is but just think: Stanley Kubrick. The final scene in question has Annie’s character fighting with her husband in their bedroom, who she seems to suspect did something terrible – maybe even murdered someone. Annie is screaming at him that she’s not crazy, she knows what he did, which leads to a physical altercation.

Every time they shoot the scene, Bloch says, “Let’s go again.” Annie asks what changes he wants but he never answers her. He just says, “Let’s go again.” That alone would drive a person crazy. But to make matters worse, everyone on set seems to hate Annie, who, by the way, is the only woman on the entire production (this is 1981 remember). So she feels super isolated outside of her assigned personal assistant, Laszlo, who’s a sweetheart.

As the night turns into day, and 1 take turns into 20, then 50, then 70, Annie really starts to lose it. She’s convinced the eye-patch that the DP wears has switched eyes. She thinks the wallpaper in the bedroom has changed color. The photo on the wall of her character and her co-star’s character turns into a photo of her and her mom. She repeatedly sees her mom in the back of the set. She thinks one of the stunt doubles wants to assault her.

Then the worst imaginable thing happens. The hospital calls and lets Annie know that her mom passed away unexpectedly. Bloch apologizes profusely. He tells Annie that he’ll get her on a flight home immediately. But now Annie is determined. She asks Bloch if he got the take. Bloch confesses he did not. “Then let’s go again,” she says. It’s clear that nobody’s leaving until they GET THIS TAKE RIGHT.

The byline of this post is, “yet another high concept idea.”

Since I know “high concept” can be confusing, I want to explain why this idea is high concept. The best way to do so is by showing you what the “low concept” version of this idea looks like.

The low concept version of this is the aftermath of an actress who’s had a long day after trying to film a scene that wasn’t working. We see her depressed and struggling and maybe her boyfriend has to build her back up again for the next day. Another version would be an actress trying to make it through a tough production in general. Every day is a challenge and she’s beaten down by the process.

In other words, straight-forward boring explorations of what it’s like to be an actress on a difficult shoot.

The second you make it 150 takes, the whole concept takes on an elevated feel. It feels bigger. It’s more intriguing. This is what makes the concept “high,” is the clever elevation of the common interpretation of an idea.

But what about the execution?

I’m, self-admittedly, not a fan of descent-into-madness screenplays for one simple reason. The screenwriter never gets the line right between keeping the script understandable and the story crazy. They always bring the craziness and messiness into the writing itself so we’re not sure what’s going on. These scripts have to be understandable even if what’s going on in the story isn’t supposed to be understood.

That’s a hard balance for even experienced writers to master.

While Bannon’s tackling of the problem isn’t perfect, he does a pretty good job. He definitely captures this character’s insanity but I still, usually, understood what was going on. I think the reason he was able to do this was because he kept the story simple.

Literally, we’re on the same set filming the same scene over and over again. So when there are crazy elements like, say, a mysterious woman that nobody else can see walking around in the background, we’re able to identify that as the lone variable that has changed and therefore an extension of Annie’s psychosis.

Plus, Bannon added some smart elements to his screenplay that exploited the idea. For example, at one point, Annie’s P.A. accidentally lets out that Howard has been telling everyone on set to be mean and isolating to Annie so he can get the performance he wants out of her.

There’s also mystery elements. The hospital calls to inform Annie that her mother passed away. But we’re immediately questioning, did that really happen or did Bloch make that up in order to get a better performance out of her? So now we have this carrot dangling in front of us, pushing us to keep walking, cause we want to know if her mom really is dead or not.

In other words, it isn’t just about doing the scene over and over again. There are other unresolved threads. Thank God for that because the movie would not have worked if that was the only thing propelling the narrative. Lots of newbie writers would make that mistake, by the way. They’d only focus on what’s in the logline – the bare-bones interpretation of the concept. But movies are too long for that. You need to keep feeding the beast – the beast being the reader – new meals every ten pages or so to keep them interested.

The irony about this script is that if it was ever tuned into a real movie, it would have the exact same effect on the real actress who took the part. She would be shooting 300-400 takes of the same scene. Cause she’s shooting multiple takes to get each of the takes right within the story itself. You’d have to be crazy to volunteer for that. But maybe that’s the point.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Your most clever dialogue lines are going to stem from YOUR CONCEPT. Your concept is the primary generator of all that is unique within your script. So if you want to write clever lines, lean into the concept. For example, early on, the hair and makeup guy comes up to Annie before she’s about to shoot her scene and he says, referring to her exhausted face, “Are those dark circles mine or yours?” Annie responds, “I think they’re mine.” “You make my job easier every day.” So, why is this a clever line? Cause the obvious line is, “You look like s—t. We need to get you back in makeup pronto.” That line contains the exact same sentiment, but is on-the-nose and, therefore, boring. A compliment that’s actually an insult delivered in a way to make the heroine feel bad about herself – that’s good writing.