Genre: War/Period/Real-life story

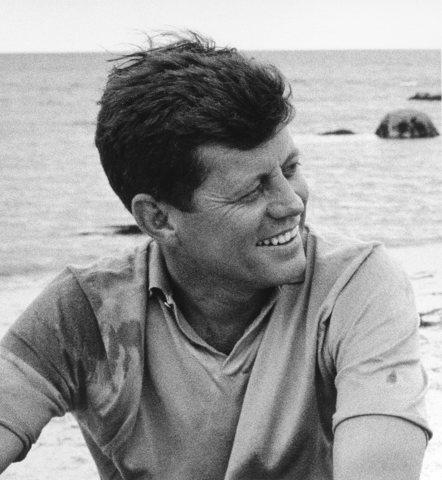

Premise: The story of how a young World War 2 Navy commander saved a group of men after their ship was destroyed by the Japanese. That man? John F. Kennedy.

About: This script made a lot of noise a few months ago and will probably end up pretty high on this year’s Black List. Although the script went into just about every major production company in town, there hasn’t been any mention of a sale yet. Should it indeed finish high on the Black List though, expect that to change. Co-writer Evan Kilgore is a novelist with 4 books to his name and his writing partner, Samuel Franco, executive produced 2014’s small indie film, Affuenza. In other words, Hollywood had no idea who these guys were. Well, they know now!

Writers: Samuel Franco & Evan Kilgore

Details: 117 pages (5/4/15 draft)

I have to give it to Franco and Kilgore (that sounds strangely like a 1930s comedy duo). They may have discovered the most genius idea ever. First off, what are movies about? They’re about heroes. And what bigger hero is there than John F. Kennedy? So already, this writing team has tapped into an extremely marketable character.

But wait, there’s more!

The problem with JFK is that all his stories have been told. Or at least, THAT’S WHAT WE THOUGHT! Franco and Kilgore discovered this long forgotten heroic war story of JFK’s. And guess when that story takes place? World War 2. World War 2 is one of the easiest subject matters to market in the movie industry.

So let’s recap. We’ve got…

1) One of the greatest heroes in American history.

2) A little-known heroic story from his past.

3) A World War 2 setting.

As they’d say on Seinfeld: “It’s gold, Jerry! Gold!” However, there’s this strange Dallasian cloud hanging over this project. Despite having all these elements in place, despite it going into every territory in town, it didn’t sell. What does that mean? Could it be that the script’s bad? That’s what was on my mind when I picked Mayday 109 up. Let’s see if we can get a better understanding of what went on here.

JFK was a kid with way too many health problems. He was supposed to die numerous times growing up, but he always seemed to fight his way through it. And if there’s anything this first act is about, it’s about how JFK never stops fighting.

At Harvard, he competes in the Swimming Championships despite having a 101 fever. When his older brother, Joe, throws it in his face that he’s not up to snuff, JFK challenges him to a sailboat race. Despite never having beat his bro before, he does it this time. JFK don’t give up and don’t back down. Betta ask somebody.

Cut to the Japanese bombing Pearl Harbor and JFK wants to go to war, something his father is against. JFK goes anyway and within a few years becomes the Captain of a Patrol boat. This doesn’t sit well with the crew, who believe it’s the Kennedy name that got him the position, not his actual ability.

Before he can dissolve that tension, their ship is rammed into by a giant Japanese destroyer. His men are scattered everywhere and somehow JFK is able to save 10 of the 12 crew, getting them over to a nearby patch of land.

From there, the group must make a tough decision. Do they try and swim to a nearby island that gives them a better chance at contacting help? Or stay here and wait for someone to pick them up, a decision that could end with the Japs finding them first.

Kennedy convinces the reluctant group to swim, and that begins an island-hopping adventure where Kennedy swims from island to island looking for friendlies. Eventually, he finds some locals, carves a “help” message into a coconut, and has them travel to a nearby base. This coconut would later become famous, as it’s one of the reasons Kennedy was able to become president of the United States.

The cool thing about writing a true story is that everything’s all plotted out for you. Sure, you need to cut some things and move other things around, and maybe even get creative with the order in which the story is told. But if you’ve found a good real-life story, you have what all screenwriters dream of – a defacto outline ready to go.

Mayday 109 has that. After the crash, you’ve got that strong goal (get to safety). The stakes are high (Japanese boats heavily patrol the area), the urgency is there (they have no food, no water. If they don’t find a solution soon, they die). And yet something’s missing. What it is, I’m not sure.

My initial instinct is that the story’s too chaotic. It doesn’t have the proper structure in place to take advantage of the dramatic problem. I’m reminded of another boat wreck movie, Titanic. One of the reasons James Cameron’s movie worked so well was because he designed his story to milk the tension, to milk the suspense.

The Titanic doesn’t just hit an iceberg and go down 2 minutes later. That would’ve been chaotic and crazy, but it would’ve been over within 2 minutes! Instead, they hit the iceberg and there’s this realization that the ship is going down, but it’s going to take a couple of hours. This means that everything that happens from that point on, even basic conversations, are going to have an undercurrent of suspense to them. Because we know the end is coming. And everyone’s running out of options as far as what to do.

Here in Mayday, it doesn’t feel like that kind of thought – the kind that maximizes the suspense – has been put into this. There’s more of a “moment-to-moment” approach, where we’re simply trying to solve immediate problems (Should we swim to the next island? Yes or no?). And while that kind of storytelling is perfectly valid, it can become exhausting.

And repetitive too. The script is pretty much about Kennedy swimming. A lot. If I’m being honest, I got sick of that. And that’s supposed to be the core of where the story’s excitement comes from.

Finally, I feel like the character stuff was a bit on the nose, specifically JFK’s relationship with his father. We never go beyond the basic, “Dad doesn’t believe in me” stuff, and it kept the script from really resonating on a deeper level. For example, we get lines like JFK saying to his dad, “Just once believe in me the way you believe in Joe.” That line can work if the rest of the dialogue is deftly written. But if the rest of the dialogue feels surface-level and on-the-nose, lines like this stick out as a problem.

As I’ve said to you guys before, the key to making a script really resonate with the reader is to do so on the character front. You can have a wild captivating story like this one. But if you don’t create a couple of fascinating relationships within the chaos that need to be resolved, each which strike to the core of who your characters are and what their problems are, the story will sink.

Not to get all James Cameron on you. But Rose from Titanic is the perfect example of this. She was trapped in a life that prevented her from being who she wanted to be. Her relationship with her fiancé represented this. So when she finally broke away from that, it was emotionally cathartic for the audience. There’s an attempt to do something similar here with JFK and an ensign who doesn’t like him, but again, it happens mostly on the surface.

And I don’t want to be too down on the script. It’s not a bad screenplay. I think there’s just an element to the story that hasn’t been realized yet. I hope the writers figure out what that is, because if they do, I could easily see someone like Robert Zemeckis coming on and directing this. It seems like it’s right up his current wheelhouse.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I am hereby limiting ALL SCREENWRITERS to only THIRTY DASHES (outside of sluglines) in each screenplay they write. NOT A DASH MORE! The overuse of this inorganic-looking character can quickly make a screenplay look like a technical document. Remember, the uglified formatting of a screenplay ALREADY makes it look too technical. You don’t want to add anything that’s going to accentuate that. If I were to estimate how many times the dash was used in Mayday 109, I’d say easily in the neighborhood of 1500 times. It really killed the look and flow of the script.