Genre: Independent/Romantic Comedy

Premise: A Texas Lottery fraud investigator investigates a woman who has won the lottery three times, which amounts to septillion-to-one odds.

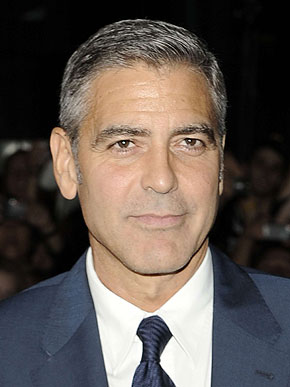

About: The hottest spec in town right now is Septillion to One. The quirky story has Alexander Payne circling and as soon as you get Payne onboard, you’re in the Oscar discussion. Which means the script will probably get someone like George Clooney for the lead, and I’m guessing Olivia Wilde for the co-lead. But what about our writers? Well, the writing team consists of Adam Perlman, who wrote on Aaron Sorkin’s The Newsroom, and Graham Sack, who doesn’t have a writing credit to his name. Sack was a child actor, however, known for such movies as Dunston Checks In and Miracle Child.

Writers: Adam R. Perlman & Graham Sack

Details: 119 pages

Many people equate selling a screenplay to winning the lottery. They point out all the scripts registered by the WGA each year and how only 75 of them sell, or something ridiculous like that. The truth is, the odds aren’t as bad as you think. I mean, how many screenplays are really written each year? Maybe 100,000? If 75 of those sell, those odds are a hell of a lot better than septillion to one.

Plus, unlike the lottery, skill factors into the equation. You can game the system with a couple of hacks, dramatically increasing your odds. Writing in one of Hollywood’s favored spec genres increases your odds. Making your main character a male between the ages of 30-50 increases your odds. A high concept increases your odds. If you’ve added enough of these hacks, and you’ve put a lot of time and effort into the craft, your odds of selling a spec aren’t that ridiculous at all.

For whatever reason though, despite KNOWING these hacks, tons of writers ignore them, pushing the odds out of their favor. Doing so will never skew the odds as bad as septillion to one. But they will keep you from becoming the next Septillion to One.

Texas State Lottery Investigator Clark Hauser is a stickler for the rules. And when I say stickler, I mean he went after his own step-father for taking bribes. Of course, that was back when Clark worked for the FBI and his step-father worked for Congress. And it was because his step-father worked for Congress that he was able to pull some favors and get Clark fired for coming after him.

Now Clark is stuck in the miserable position of working for the Texas State Lottery. And to add insult to injury, his step-father has primary custody over his daughter, Megan. Not only that, but Step Daddy wants sole custody. There’s nothing Clark can do for this girl anymore, he points out. If his daughter’s going to flourish, she’s going to need Grandpa’s money.

But Clark’s luck is changing. When the Texas Lottery starts vetting its past winners to find a poster-worthy candidate to sell a flashy new lottery drawing, Clark becomes aware of Joy Taylor’s story. Joy has won THREE lotteries in three different states. The odds of that happening are so astronomical, Clark knows she’s cheating. All he has to do is prove the scam, and his job prospects will go through the roof.

Despite Clark clearly liking Joy, he has always been, and will always be, about the rules. And even as their friendship grows, Clark continues to accumulate evidence that will help him prove that Joy’s a sham. The problem is, nothing he finds sticks. And if Joy is guilty, she seems to be the most casual most unworried suspect in the world. Could it be that Joy truly is the luckiest person in the world? Or is there something more sinister going on here?

Scene construction is one of those quick ways for me to determine whether I’m dealing with an amateur or a pro. If a scene is constructed in such a way that indicates an understanding of the craft, I know I’m in for a good read. If there is no form whatsoever in a scene – just people talking, babbling on endlessly without a point – I know I’m about to check into the Boredasaurus Hotel.

So when Clark first comes to question Joy about her amazing luck, the scene takes place during a bingo game, with Joy as the presenter. Therefore, Clark is forced to ask Joy questions WHILE she calls out numbers to the crowd. It’s little things like this – an element that’s agitating the conversation – that tell me I’m dealing with a pro. You never want to make things easy on your characters, even conversations. This choice may seem insignificant to the uninitiated. But it tells me I have a real writer on my hands.

We have the basics taken care of as well. Clark’s boss wants to use Joy as the poster-girl for the upcoming mega-lottery draw in a week. Clark knows that if Joy’s a fraud, she’s going to destroy the public’s trust in the lottery. So he makes it his goal to find out her scam before the lottery has the opportunity to embarrass itself. There’s your “U” in GSU. One week to prove she’s a cheater.

If the script has an Achilles heel, it might be Clark himself. The guy is super annoying. He’s such a stickler for the rules that you feel like if you ever had to spend five minutes with the man, you’d shoot yourself in the face. I mean who likes sticklers? That quality is almost universally saved for the villain (think Ed Rooney in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off).

So what do they do to cancel our hatred out and actually make us root for the guy? They start by giving Clark a daughter who he loves more than anything. It’s hard to dislike dads who will do anything for their daughters. I mean Clark is willing to give up every penny he has to send his talented daughter to the best music school in the country. Audiences absolutely LOVE selfless people. They love people who help others. And they love dads who put their kids first.

The writers also create a villain who’s way more of an asshole than the hero is annoying. The step-dad here tells Clark he’ll pay for Megan (the daughter) to go to the elite school, but only if Clark gives him full custody. He also regularly reminds Clark how pathetic he is and how far he’s fallen. Kind of makes you forget about the whole stickler issue.

I’ve seen the “make your hero more likable by making the bad guy more hateable” approach used to great effect. They actually do it a lot in the reality show, Survivor.

I’ll notice, for example, that I don’t particularly like one of the contestants. But as soon as the show builds up a villain who bullies that contestant? I can’t root for that character enough. The show is so aware of this secret power that when their big villains get voted off the show, they use clever editing and selective scenes to create ANOTHER villain out of the remaining contestants, just so it builds up support for the remaining players.

Finally, if you want to study how character flaws work in screenplays, find this script and read it. “Septillion” puts heavy emphasis on Clark’s obsession with the rules (his flaw). That’s what he needs to overcome to grow as a person. (spoilers) So the end of the script puts him in a position where he can either continue to follow the rules (and in the process screw over Joy) or loosen up (let Joy get away with it). It’s a little heavy-handed and on-the-nose but it’s this over-the-top quality that helps you see how arcing works. A great character arc is yet another script hack you can use to increase the odds of winning the spec lottery.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Child custody is one of the most effective emotional plotlines you can add to your screenplay. If you create a situation where your main character doesn’t have primary child custody, and over the course of the screenplay make it more and more likely that he’ll lose custody, that’s almost guaranteed to pull a reader in. No one wants to see a parent who loves their child lose that child. So know that this subplot can be used to great effect to emotionally manipulate and pull a reader in.