Heat meets The Town meets… Secretariat?

Genre: Crime

Premise: A horse veterinarian who uses his practice as a cover to treat injured criminals finds himself targeted by a corrupt cop, who needs him to help rob the Thoroughbred Cup.

About: This script just sold for a million dollars to Amazon, which beat out Netflix in the bidding. We don’t get many big spec sales these days unless they’re in the short story format, so this is exciting. It comes from the writer of Ballast, that nifty script about a car ferry that has a bunch of its cars rigged with bombs. Some thought it was a little too “thinking man” for a fun action script but I liked it. Today’s script feels like it better matches the writer’s heady-thoughtful writing style. Let’s see how it turns out.

Writer: Justin PIasecki

Details: 116 pages

Succession’s Jeremy Strong to level up to feature film leading man?

Succession’s Jeremy Strong to level up to feature film leading man?

By the time you read this, screenwriters in Hollywood may be on strike. It’s going down to the wire. Obviously, this is going to be rough on everyone. If you’re a writer, there will be no work. If you’re a studio, you have nobody to write your movies or shows.

However, the one good thing to come from an impending strike is that it gets studios trigger-happy. They need content in case the strike goes on for a while. Which is how we end up with today’s sale. This script is said to have been purchased exclusively because of the impending strike. So good for Justin for taking advantage of an opportunity.

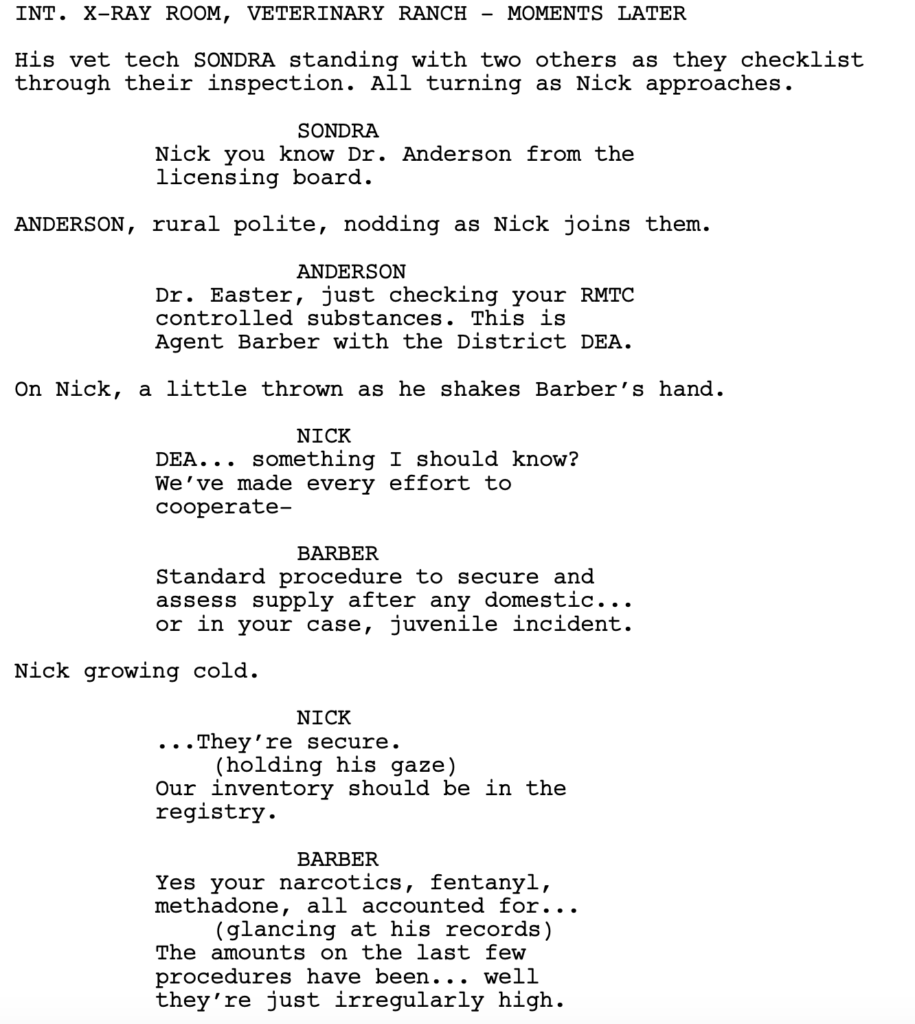

Nick Easter, a 40-something horse vet, has been a Chicago guy his whole life. Nick’s been dealt a few harsh blows lately. His wife died and his 17 year old addict son is stuck in juvie. Since regular vet work isn’t paying the bills, Nick has taken to outfitting his practice with a secret underground medical facility for gnarly Chicago criminals.

It’s pretty easy to pull off, actually. You just order a little extra horse medicine and you use it on the humans. Well, easy is about to get hard. Because a group of Chechens try to steal Nick’s boss’s medical shipment, which just happens to have a plethora of heroin in it as well.

The cops think it’s a standard drug deal gone bad until they find traces of horse manure in the truck. This sends them on a roundabout trip that ends up at Nick’s secret doctor’s office. Surprisingly, the cop who discovers him doesn’t want to arrest him. He wants Nick to help him rob the place where Nick works, Hawthorne Racetrack. The Thoroughbred Cup is coming up and millions of dollars are going to be bet there that day.

Of course, Nick says no way. But our cop reminds him that he just might pay a visit to the local juvie hall and, oh, I don’t know, stash some heroin under Nick’s son’s pillow. If he does that, juvie may be a fond memory compared to where the son is going next. So Nick is stuck doing the job. Saddle up everyone. We’re about to experience the mane event.

Something it took me a really long time to figure out was that crime is a great way to write a character piece that Hollywood actually wants to buy. When I first started writing, I was writing all these dramadies that were, essentially, character pieces with a little bit of humor in them. Nobody wants to buy those. Those scripts only get made if they’re directed by the writer themselves.

Crime, on the other hand, sells. Because crime ups the stakes of everything. Now there are guns involved, drugs involved, theft involved, people are actually dying. You can build a marketing campaign around that. Heck, just put a well-known actor on a poster with a gun and people will go to see that movie. It’s much harder to get investors or studios if all you’ve got is characters trying to make it through life.

Case in point, Red Rocket is one of my favorite movies of the last two years. But NO ONE HAS SEEN IT. Cause it’s an offbeat coming-of-age love story. The only reason it got made was because the writer is well known and he was also the director.

Which is me telling you, if you’ve got a character piece that doesn’t have a hook, consider turning it into a crime film. Cause it all of a sudden becomes a million times more marketable. It’s one of those few times that crime does pay.

That doesn’t mean writing these is easy. With crime films, the problem is always that they feel the same. Grungy looking serious people dealing with criminal problems, occasionally pulling out their guns and firing them then jetting off until they deal with their next skirmish. So how do you differentiate yourself?

You gotta find one or two unique elements to hang your concept’s hat on.

Imagine yourself hanging out with a friend, who, of course knows you’re a screenwriter, and they ask you, “What are you working on right now?” Imagine answering that question. Would your answer make that friend believe that you’ve got something cool on your hands? Or would your pitch, no matter how you spun it, sound like every other crime movie out there? Cause if it’s the second one, you’re working on the wrong idea.

With this script, it’s the horse angle. Why is that unique? Cause I’ve read hundreds of crime scripts and I can only think of a couple that dabble in this subject matter. That’s it. That’s all you need. If you have that, chances are you’re in good shape. If you would’ve told me it’s a script about bank robbers or drug dealers or a guy who gets in trouble with the Russian mob, we’ve got a problem.

The big payoff scene in Stakehorse is reminiscent of the famous bank robbery in Heat. It’s not quite to that level. But it has the same intensity as that scene. In it, Nick’s boss takes a group of criminals on one of those truck-train combos that can ride on train tracks. Knowing when a brinx truck is going to be coming to a train crossing, they’re able to close the crossing gates, blocking the truck (as well as the rest of the traffic) there.

They then blow the tires off the thing and use some elaborate tools to get into the truck. It’s a really cool scene mostly due to the fact that you haven’t seen it before. It’s SO HARD in these crime films to come up with fresh set pieces but this was totally fresh. My one complaint – and it’s something I can’t believe Piasecki didn’t think of – was that he didn’t have an unscheduled train show up, barreling towards them, adding a super intense ticking time bomb to the scene. But it was still cool!

The biggest problem I have with this script is that it reads thick. By that I mean, it’s one of those scripts where if you miss even one action or dialogue line, you might be confused. So you have to concentrate a lot more to keep up with what’s going on.

Yeah yeah. Technically, that’s what a script should be – every line contains relevant information. But you can definitely go overboard with that, and if you’re writing a script with a lot of characters and nuance and exposition and detail, it can start to feel like work reading the script.

Go back and read Friday’s script, which is one of the easiest reads you’ll have all year then read this script, and you’ll see what I mean. I’m not saying it’s a bad thing. You can certainly get away with it if you’re a good writer, like Piasecki. But I don’t like scripts where I check that page number, thinking I’m on page 30, and I’m only on page 12. That tells me your script is too dense, in description, information, plot, or all three.

Still, I thought this was good stuff. If you liked The Town, you’ll love this script.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: There’s always a more clever way to say something. Early on, when the cops are traipsing through a truck crime scene, they note that there are a couple of dead bodies in the back of the drug truck. How would you refer to those bodies in dialogue? Most writers would write something like, “We got a couple dead bodies back here!” The less lazy writer might add a little more flourish, saying something like, “We got two big beefy corpses back here.” Piasecki goes with something better than both of these: “I figure we got a buy gone wrong. Driver catches an unlucky one in the front. A hundred and twenty kilos of brown and five hundred pounds of dead Chechens in the back.” “Five hundred pounds of dead Chechens” is a much more clever way to refer to two dead bodies.