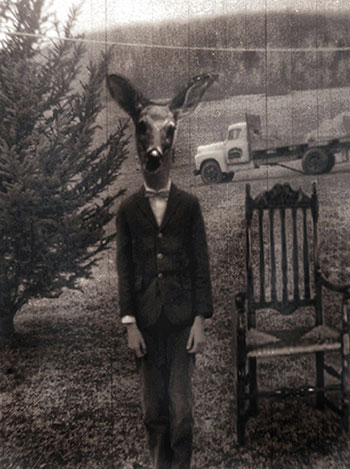

Genre: Horror

Premise: Years after two girls sacrifice their friend to an entity they refer to as “the boy,” the less violent of the two gets out of prison and tries to rejoin society, only to start seeing the boy all over again.

About: This script finished second on the 2015 Blood List to “Eli.” Writer Owen Egerton has a couple of low-budget produced credits, but this is the first time he’s written a genre piece. Take note my friends. You want Hollywood to start looking your way, write in a genre they like to sell movies in. Simple as that.

Writer: Owen Egerton

Details: 96 pages – 5/28/15 draft

Forgive me Lord of Films for what I am about to say.

Raiders is a dead franchise.

And if we’re really being honest? It was a dead franchise since the second the first sequel came out. They haven’t made one good Indiana Jones film after the first one. “Oh, but the third one, Carson! The third one was good!” No it wasn’t. It was a little bit better than the second one, which sucked so everybody was TRICKED into thinking it was good, much like Revenge of the Sith was a bad movie but looked good after Attack of the Clones.

Why are they making ANOTHER Indy movie? We’ve already got our awkward old Indiana Jones film to watch if we so desire. Now you’re going to add a really old Indiana Jones film to the mix? The man is going to be 80. I know Harrison Ford stays in great shape but come on. Say this out loud: “I’m going to watch a movie with an 80 year old action hero.” That’s like trying to pass Betty White off as Jennifer Lawrence. No amount of make-up, lighting, or Hollywood trickery is going to help.

I’m really confused, guys. Between this and Ghostbusters XX chromosome edition, we’ve taken nostalgia to an uncomfortable level. And what does it say about nostalgia when all of it sucks? Aren’t you killing nostalgia when you do that? Aren’t we killing the very thing we desire?

I could talk about this all day but we do have a script to review, one that doesn’t have Indiana Jones in it, thank god. But it does contain an old horror trope that threatens to turn our horror tale into a cliche. Will that choice doom today’s offering? Or will the script manage enough originality to come out on the right side of the pile? Let’s find out, boy!

Pre-teen friends Rebecca, Marina, and Lily are puttering through a dying forest on an overcast day, seemingly enjoying each other’s company, when all of a sudden Rebecca grabs a rock and cracks it over the back of Lily’s head. As Lily lays dying, Rebecca demands that Marina drag her into the lake and drown her, all in the name of pleasing “him.”

“Him” is the “the boy,” a ghost child from the early 20th century who’s become the girls’ friend, but only if they sacrifice their buddy for him. Rebecca and Marina complete the sacrifice, but since they’re 12, aren’t exactly whizzes at covering up the crime. As a result, they each go off to separate juvenile halls, and eventually to prison.

Marina gets out when she’s still in her 20s and moves in with her older sister, Alice, who’s helping her sister mainly out of guilt for not visiting her. Alice has an 8 year old son, Bryce, who takes a liking to Marina, until he finds out about her past. When he does, he starts looking up “the boy” online and becoming obsessed with him.

Also obsessed with Marina and the boy is Alice’s dick boyfriend, Will, who keeps trying to get Marina to co-write a book about the incident in hopes of cashing in. It doesn’t take long for Alice to dump his ass. Unfortunately (or fortunately, depending on how you look at it), only a few days later, Will turns up dead. Guess he can write his book in dead font.

Around this time, Bryce begins acting funny, and hints to Marina that he now sees the boy too. Marina has spent every day since she was 12 convincing herself that the boy was a figment of her imagination. And now Bryce has to come along and screw that all up.

Eventually, Marina heads off to find the third member of this equation, good old Rebecca. But Rebecca’s not doing so hot. And her visit leads Marina to find a horrible truth, one that will come back to haunt her, and one that will finally shed light on what happened that day in the forest.

The Boy is a good example of a well-executed horror premise… and nothing more.

This isn’t to disqualify the script. Writing anything that keeps a reader’s interest the whole way through is amazing. 99 out of a 100 scripts cannot achieve this. Shit, 70 out of 100 scripts can’t keep you interested past page 5! So let’s not discount what Egerton’s achieved here.

But The Boy’s fatal flaw is that it doesn’t take chances. Chances are what separate your script from other well-written material – the special sauce that helps it rise above “worth the read.”

Instead, The Boy hits all the typical beats these kinds of movies hit. The creepy boy who appears in the corners of rooms, who leaves notes in crayon, who’s there and once you blink he’s gone. We’ve got the “researching the boy’s past” section, and of course the big fire that killed him and his family.

I was invested, but all of these familiar story beats kept a little bell ringing in my ear: “You’ve seen this before.” “You’ve seen this before.” “You’ve seen this before.” The writer seems to go out of his way to remind you that you’ve already lived through this ghost tale.

That’s not to say The Boy didn’t show flashes. For example, there’s a moment when Marina moves in with sis and nephew and they’re having dinner for the first time. Alice and Bryce are about to chow down but stop when they see Marina whispering grace to herself.

Why does this moment matter? Because it shows that the writer is thinking about what these characters’ lives must really be like. Marina has spent her entire adult life in prison. Knowing that prison is a religious place, Egerton surmised that Marina would probably be religious. And because he included that specificity, Marina felt real to us.

A huge mistake beginner writers make is they don’t think to differentiate their characters. They construct any perceived differences in their characters on “feel.” To them, Marina “feels” different from Alice in their head, and therefore that difference will come across naturally on the page.

That’s not how screenwriting works, unfortunately. For readers to see differences, they must see DIFFERENCES IN ACTION. If one character says grace while another says nothing, that signifies to them a difference in character.

Speaking of character, Egerton made a critical choice early on to show us the original flashback where the girls attack their friend. He then keeps us with Marina so that we see her grow up in juvie and prison.

This allows us to get to know Marina so that when she moves in with Alice, we feel like we know her. I’ve seen the opposite approach to this where writers start with their hero as they’re getting out of prison. The advantage to this is that Marina is more of a mystery to us, and the hope is that the reader will want to stick around to learn about her.

Both choices are valid, but the first stresses character development, making us feel closer to the character. Since connection between hero and reader is one of the most important things in storytelling, this is a smart way to go.

Now advanced writers can pull that kind of connection off quickly (sometimes in a single scene!). So they might go with the mystery approach, knowing that when they need you to connect, they can do so quickly. But when you’re still in the learning stages of the craft, taking the longer drawn-out approach is probably the safer bet.

The Boy also has a couple of memorable scenes, which is essential for any good horror script. Marina’s visit with adult Rebecca freaked me out. And I’ll be the first to admit I didn’t see the ending coming. Bryce potentially being the new version of “the boy” also lead to a couple of nice moments.

Still, I kept waiting for this to distinguish itself as its own screenplay and not an ode to all the similar films that came before it. But it never did. And that left me sad. Sad like the boy.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The easiest way to show differences in characters is to place them in the same situation and have them act differently. In the example I mentioned above, where Marina says grace and Alice does not – that difference hits us right between the eyes. That doesn’t happen if, say, we show Marina go to church while Alice is at work. We’d know Marina was religious, but miss out on the opportunity to show that Alice isn’t.