Genre: Comedy/Noir

Premise: (from Hit List) Following the disappearance of the book fair money he was entrusted to protect, a lactose intolerant middle school student with an addiction to dairy items must hone his detective skills to investigate the “seedy” under- belly of his school. Think MALTESE FALCON by way of DIARY OF A WIMPY KID.

About: Today’s writer has had an envious eduction. He got his undergrad at the NYU Tisch School of Arts then got his MFA from the USC School of Cinematic Arts. This script won top comedy in the Tracking Board’s feature contest. It has since attached Ed Helms to star. I will put my hard earned money down for opening night if Helms plays Sid, the fifth grader.

Writer: Surjyakiran Das

Details: 109 pages

These scripts pop up once a year. A young kid, between second and seventh grade, performs some adult investigation. The hero is usually lactose intolerant for some reason. The concept’s irony wins the Black List/Hit List voters over every time (“A little kid! Doing an adult job!”) so as long as the script is reasonably well-executed, it will get recognized.

This is actually how Rian Johnson (Brick) came into our good graces; before the dark times, before the Empire. I’ve found that for these scripts to be memorable, and not just coast on their irony, the writer needs to have a genuine voice. They need to possess a darkly ironic sense of humor. And the dialogue needs to be killer. Achieving this is a rare feat, like getting Scriptshadow commenters to post positive comments about The Perfection. Let’s see if today’s writer pulls it off.

Sid Ray was a fifth grader who had it all – he was the Head Hall Monitor, a position that earned him the kind of respect an otherwise tiny nerdy lactose-intolerant kid would never be able to achieve. But when Sid loses the cash box for the school book fair, he falls out of favor with the principal and becomes just another kid.

Sid’s poison is milk. He loves it. But because he’s lactose-intolerant, he passes out whenever he drinks it. Someone took advantage of one of these collapses on the day the cash box disappeared. Luckily, an opportunity to get back on top arises. The Confection Candy Company comes in and promises students 20% commission on any sales they make of Confection Candy. When large amounts of unaccounted for Confection chocolate start getting sold in the hallways, Sid realizes that if he can solve this case, he can get back into the school’s good graces.

Sid teams up with Abigail, the editor of the school newspaper, and starts investigating the usual suspects – namely bullies. He eventually finds out his primary suspect, Frankie, is responsible for the peddling, and it looks to be case closed. But when a couple of last second loose threads contradict Frankie as the chocolate czar, Sid must confront the possibility that the last person he expected is responsible for the crime, the last person anyone expected, in fact…

If that plot summary was a little confusing, it likely has something to do with me dozing off a few times during the script. This is every writer’s nightmare, I know. A reader who’s so not into your story that they’re actually falling asleep during it. Why does it happen? It can be any number of things. The reader isn’t into the subject matter, in which case it’s not your fault. There was a little of that going on here. The characters and plot choices are bland, or include stuff you’ve seen before. Also some of that going on here. In the end, it happens when a story is harmless – the kind of script that’s good enough to rise above a reader’s baseline level of interest, but unexceptional enough in any one area to keep that interest throughout the script.

What I’m looking for in a story like this is a main character who’s clever. That’s what makes these detective stories go round – characters who are smarter than and can outwit everyone else. The best way to achieve this is through an early scene where your main character figures something out in a clever way – a way where the reader is impressed with how they did it. If you can achieve this, you’ll have the reader for the rest of the script.

Confection’s version of this scene is a sting operation to catch an artist bully who routinely steals markers from art class. To catch him, Sid has an ally switch the bully’s markers with non-working markers when he’s not looking, then Sid confronts the bully in the bathroom, asking to see the contents of his backpack, finding the stolen markers inside (but not the real markers, the ones that were planted), asking the bully where he got them, the bully saying they’re his own markers, getting the bully to use them in front of him, none of the markers working, therefore “proving” he’d stolen them because why would he have markers in his backpack that didn’t work? What???

A few of you might be saying, “Come on, Carson. Lighten up. It’s a movie about a fifth-grader.” But see, that’s the thing. Once you start coming up with excuses why you don’t have to try as a writer, you’ve lost. And this actually goes deeper than that. Your characters’ early actions have a disproportionate impact on the reader because this is the time when the reader is forming their opinion about your hero. If they can either take them or leave them, you have an uphill battle the rest of the script. Cause it’s really hard to keep a reader interested if they’re neutral about your hero.

I want to make clear, however, that this script is way better than your typical amateur script. You can see the Tisch and USC schooling at work. The structure is air tight. There’s a strong objective pushing the plot forward. The aforementioned ironic concept is something that most aspiring screenwriters never learn how to do. The writer has a clear love and appreciation for noir movies and there are some clever ways in which he infuses noir tropes into the narrative (the milk substituting as alcohol was my favorite). This script would finish top 10 in most of the screenwriting contests it entered.

But there is a difference between scripts that place high in contests and scripts that get Hollywood interest and it basically amounts to a more striking voice, more unexpected choices and, finally, crafting a story where you’re routinely ahead of the reader. There were so many moments during this script where I thought, “Either this is going to happen or that’s going to happen,” and one of those two things would happen.

A good writer will write a script where the reader thinks “Either this is going to happen or that’s going to happen,” and then something totally different happens. And it’s not just a random thing. It makes sense. Those are the writers who stand out. As much as it kills me not to be able to share it with you guys, that script I brought up in the comments last week that I consulted on which would make my Top 25 (but the writer wants to keep it private) – that script surprised me every single scene. Every time I thought the writer was going to zig, he zagged. That kind of writing takes work because it means you must routinely ignore the quick easy choices and dig for something better. And whenever you do that, it takes way more time than you want it to. Which is why most writers don’t bother. It’s easy to stick with the obvious stuff everybody else is using.

I’d imagine that if this does get made, it’s going to look better onscreen than on the page. It’s going to be shot in a noir style, which is going to look unique for a movie about grade school. The soundtrack will be jazz, which will also contrast against the school setting. The main character wears a fedora and has long voice over monologues. That might be what turns this from ordinary to extraordinary. But if we’re just talking about the page, I’ve read half a dozen versions of this script already. You can probably find the reviews on the site.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The invisible dialogue break. Here’s a visual example of the invisible dialogue break…

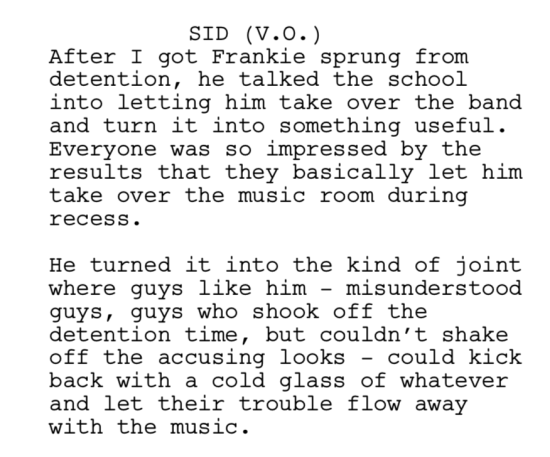

I’ve been seeing this more and more over the last couple of years, and while it’s not something purists are going to like, I see no harm in it. I know that sometimes really long blocks of dialogue can be intimidating. This allows you to break them up in a non-invasive way. In the past, writers would use the parenthetical “(beat)” to signify this break. But because “beat” is a technical term, it risks taking the reader out of the story, even if just for a second. The invisible dialogue break prevents that. And as long as you don’t overuse it, I see it as a viable option.