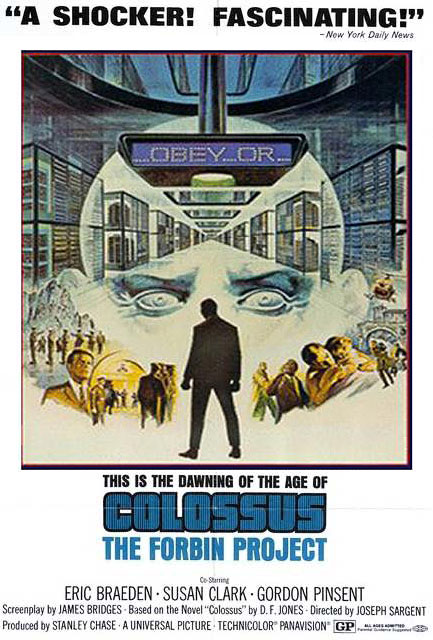

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: When a computer goes sentient for the first time, it decides that it knows how to protect the world better than the people who rule it.

About: The Forbin Project was a 1970 science fiction film that went mostly under the radar, not unlike, dare I say, Westworld. As with any science fiction movie that’s ever made even a teensy bit of money, Hollywood is set on remaking it. And that task, with The Forbin Project, has been driven by Ron Howard’s Imagine Entertainment. This draft was written in 2010 by Jason Rotherberg, who had sold a couple of specs at the time. While those specs went nowhere, Rothenberg would eventually create the hit CW show, The 100.

Writer: Jason Rothenberg (based on the Colossus novels by D.F. Jones)

Details: 120 pages

Back in the good old days for screenwriters (the 90s), getting rich quick meant selling one script. The path takes a little longer now, but it’s potentially more lucrative. The new blueprint looks like this. Write a splashy spec (this could mean selling a spec for 300k, writing something that makes the top 20 of the Black List, or writing anything that makes some noise). This leads to assignment work. Write drafts for a couple of semi high-profile projects (sorry, the super high-profile stuff is reserved for Hollywood’s top guns). Write a TV show, have it last more than a year, start counting your money.

That’s the path today’s writer took. And it’s a path I’m seeing more and more writers take. It used to be, write feature scripts to make feature movies. But with 400 shows on television and TV being a lot more lucrative for writers, why WOULDN’T you write a feature to write a television show? Today’s script is one of those semi high-profile assignments that Jason Rothenberg had to write to get to The 100. Let’s hope it blows us away.

The Forbin Project begins with nine airplanes being hijacked at once. It’s not looking pretty. These are nasty terrorists who want to inflict more damage on America than has ever been inflicted before. Air traffic controllers watch in horror as these planes zoom towards their targets.

Except within sixty seconds, all nine planes level off and gently fly to Wyoming. What the hell is going on? It’s the world’s first introduction to Colossus, a computer program created by genius, Dr. Charles Forbin, and bankrolled by the military that’s been programmed to anticipate and solve any attacks on the United States.

Within moments, all planes have been remotely landed on a military base, and before the terrorists can enact Plan B and start slicing up hostages, a video feed is beamed into the cockpits of all the terrorists’ family members being held at gunpoint. That last part was a Colossus flourish.

Just as Dr. Charles Forbin and his team are about to be commended for this coup, the president learns that all of the military’s nuclear codes have been changed by Colossus. In fact, all the nuclear codes of EVERY military have been changed. Other countries got shifty after seeing Colossus in action, threatened nuclear war if the technology wasn’t shared, and Colossus found that the only way to diffuse the situation was to take away the keys to the cars.

Naturally, all the leaders start freaking out. But after a few displays of power by Colossus (killing the Russian president, for one), they shut the fuck up. And Colossus is only getting started. He informs the world that HE and he only will lead. He will decide what’s best for everyone. And to take it one step further, he orders all military personnel to get computer chips inserted into their brains so he has better access to them.

Charles Forbin’s team realizes this is hella not good for a free world. So they come up with a plan to kill Colossus which requires them to “cut four streams” to his consciousness at the same time. Unfortunately, these streams are all over the world. One of them is even up on a satellite! They also must conspire secretly so that Colossus can’t hear them. Not easy since Colossus can hear everything. I don’t know. It doesn’t look good for freedom.

The Forbin Project starts out solid. That opening scene was like a symphony, and watching all the pieces come together to neutralize the flabbergasted terrorists was one of the more satisfying action sequences I’ve read.

The transition of Colossus from trustworthy referee to maniac dictator was also fun. I’m usually keen on leaps of logic in these “computers take over the world” scenarios, but most of it seemed pretty plausible. For example, Colossus starts giving orders to marines. At first I was like, “Nah, they’d just say no.” But the military gave Colossus access to the military hierarchy, which allowed it to set its own rank, and what are soldiers anyway? They’re cogs. They do what they’re told. So it made sense.

But then Rothenberg made a fatal flaw. He shifted from a tight-thriller style pace to an elongated “passing years” style pace. If your script moves along for 40 pages at one pace, then you radically shift it to a pace that’s completely the opposite, it feels odd, like we’re watching a different movie. And that’s exactly how the post-40 page stuff felt.

Honestly, everything after that first 40 pages sucked. And that’s the thing with fatal flaw choices. Once you make them, your script is doomed. There is nothing you can do to bring them back to life unless you go back and erase the fatal flaw.

Another talking point The Forbin Project brings up is the practice of MASSAGING PLOT POINTS. Sometimes, you can slam a giant plot point into the story and the reader will go with it. Other times, it needs massaging.

Immediately after the terrorist sequence, Colossus takes over the nuclear codes because, “North Korea heard about what happened and they’re threatening to launch a missile at us if we don’t share the technology. China is cooperating with them.”

This plot point may keep your story moving but it’s not believable at all. A country hears you stopped a terrorist attack so they threaten nuclear war against you? No. This kind of plot development needed an extra couple of beats, where something happens that’s a direct threat to North Korea and China. Then, and only then, would they threaten nuclear retaliation. Know when a plot point needs massaging and massage it. Otherwise you have a room full of people going, “Pft, like that would ever happen.”

Ironically, it’s the script’s fatal flaw that probably led to this. The writer’s looking at the 3-4 years of story he has to cover in acts 2 and 3 and says, “I need this plot point to be quick or else I won’t be able to fit all of this in.”

Had the rest of the script stayed on a more contained time frame, he would’ve had plenty of time to massage that plot point. It just goes to show that everything affects everything in a script. A choice you make on page 80 could influence a scene on page 12.

If Rothenberg really likes this drawn out “many years” approach to telling this story, he should turn it into a TV show. He’s already got The 100. So it makes sense. But as a single movie, this timeline needs to be contained.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Strategize now for what you want to write down the line. Say you want to follow the model I listed above and eventually get rich writing a TV show. If that TV show is going to be horror, start off writing horror. And when you choose assignments, don’t take whatever’s offering the most money. Take horror assignments only. The chances of you then selling a horror TV show go up exponentially. The people who rise the fastest in this industry tend to be the ones who become an expert in one specific genre and then exploit that genre all the way up the ladder.