Genre: Sci-Fi Drama?

Premise: (from Black List) An exploration of relationships as a man witnesses different types of love across the ages.

About: This one finished pretty high on last year’s Black List. This is Tom Dean’s breakthrough script.

Writer: Tom Dean

Details: 127 pages

I didn’t make it to Baby Driver this weekend. Maybe I’ll see it tomorrow and do that script-to-screen review for Wednesday. The movie’s doing quite well, which, despite my negative script review, I’m happy about. We need more filmmakers taking chances like Wright.

Speaking of a movie that didn’t take ANY chances, The House was decimated at the box office this weekend. I’m not surprised. It always felt like a lazy idea. Plus, marriage isn’t funny. If you look at the history of comedies, marriage has never been funny.

Then there’s the new Netflix show, GLOW. I don’t know what to make of that one. I’ve watched four episodes and the writing vacillates between really good and really sloppy. The majority of the scenes feel like they were filmed before anyone knew the cameras were rolling. And the main character, played by Alison Brie (the whole reason I tuned in), is inexplicably kept in the background the majority of the time. I haven’t given up on it yet. But episode 5 better be awesome.

Moving on to today’s script, I’m surprised I haven’t reviewed it yet. It’s on the Black List. It’s time-travel. Sounds right up my alley!

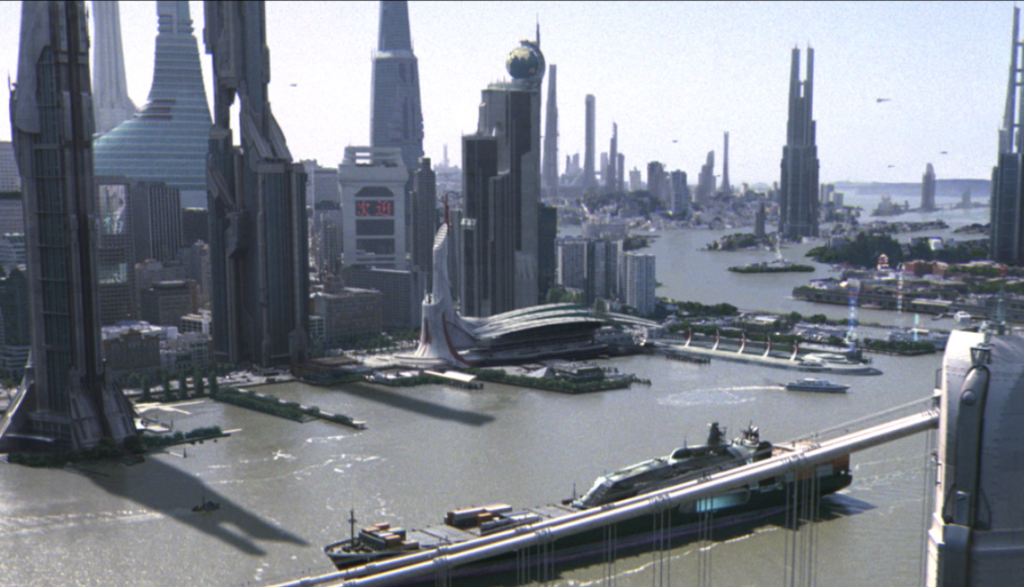

The year is 1960. Sort of. This is 1960 after the invention of time-travel. Which means there’s been some changes. Subtle changes. Like futuristic shit stitched in. But changes nonetheless. It’s here where our Narrator, who will take us through the many time periods in the story, introduces himself. He explains that it’s his job to keep lovers properly meeting each other in all the various time periods.

We first get to know Cecile and Sanjay, who live in Napa Valley circa 1820. But, once again, you have to remember that just because we’re in 1820, doesn’t mean that the characters were born in this era. Both Cecile and Sanjay are from different time periods in the future, or at least, some future after 1820. We watch both of them get in a huge fight, and then we cut to New York City, circa 2402.

It’s here where Sanjay is now a young assistant at a giant company. He’s told by his boss, Henri, to deliver a gift to Henri’s wife back at their condo. Once there, however, a 50 year-old Claire, Henri’s wife, discusses happiness and love with Sanjay before ultimately seducing him.

From there, we cut to Nice, France, circa 1930, where we meet Claire as a 25 year-old. She’s just moved here, and a young cop named Antoine knocks on her door to see if she knows anything about a murder that was committed outside. Antoine falls in love with Claire at first sight, but must use his fellow English-speaking cop to translate his love for Claire.

Cut to 40 years earlier, also in Nice, France, where Antoine is now older, or maybe younger, and is now an actor. Antoine is now in love with Roland, a 30 year-old transgender man. The two fight with each other about their future, specifically how Antoine cannot be with a transgender person.

That takes us to about page 70. And I could go on. But I think you get the idea.

The original paragraph that I was going to write here, I deleted. It was too personal, too negative. And I think Dean deserves credit for his ambition. Without ambition, we get Transformers 6. There’s something to be said for artists who stand up to movies like that.

However, I can’t get past how unnecessarily complicated this story is. There’s the time-travel mythology. There’s a complex narrative. There are tons of rules. There’s no true main character. Dialogue scenes go on forever. The fourth wall is broken. It’s over 120 pages. The characters we do get are all over the place.

For example, one character is a transgender man in one time period, and then a woman when we cut to earlier in his life. Except that he’s actually living in a later time period when he’s younger. It’s almost like the writing is done to specifically confuse us rather than entertain us.

At one point, in 1960, when our characters are going to a movie, they see this on the marquee: “George Clooney in ‘11th Avenue’ Directed by Howard Hawks. His first film after time travel.”

There are also a lot of lines like this: “If it happens you’re familiar with 1820’s Napa Valley, this version won’t look familiar at all. The architecture is limited to the style and technology of early 19th century, but it is very much lived in, developed, and flourishing.”

And then we get dialogue like this: “Okay. Well, when we travel through time, we regulate exactly what dimension it is we travel inside of. That’s why when you travel from 2500 to 1500, you don’t alter the past and create a paradox that would essentially change the course of events so that your parents would never meet and thus never have you and thus never afford you the opportunity to change the past in the first place.”

When you’re reading stuff like this while attempting to follow characters backwards through time, those characters sometimes getting older despite the year being before or getting younger despite the year being after, it gets to a point where you throw up your hands. You’re rooting for scripts that take chances. But if we’re not even sure what’s going on, how can you root?

To the screenplay’s credit, it starts to come together in the end. There was a moment where I thought, “Wow, this reminds me a lot of when I first read Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.” But whereas it was always clear in that screenplay what was going on, this one you’re in the dark the majority of the time.

The thing is, there’s a good idea in here somewhere – this concept of following love stories backwards in time. Going in reverse from each relationship to the characters’ previous relationships, and taking that further and further back until you get to the first person who started the chain. But instead we have this time travel stuff which you need Neil Degrasse Tyson next to you to explain.

So what’s the lesson here? I’m not sure. Shouldn’t new writers be taking chances like this? Isn’t ignorance, in a way, an advantage? Christopher McQuarrie stated that his best script, the one that got him an Oscar, The Usual Suspects, was written with barely any screenwriting knowledge. He said that he wouldn’t have done a lot of the inventive stuff he did had he known then what he knows now.

So why beat Dean up for that? This comes back to one of my weaknesses as an analyst, which is my defiance of experimentation. But I think my issue here is a valid one. Had their been one experimental choice, I would’ve been okay. My problem with La Ronde is that there were half-a-dozen experimental choices stacked on top of each other. And screenplays just aren’t built for that. You can get away with it in novels. Cloud Atlas comes to mind. But screenplays are limited in the types of stories you can tell with them. That’s why this didn’t work for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you’re going to write long scenes, make sure there’s enough tension to sustain them. If there isn’t, we won’t have enough patience to follow the scene through. So there’s a scene in La Ronde where Sanjay brings a gift to his boss’s wife, Claire. He is supposed to slip the gift in the condo and then leave. It is imperative he not get caught. But the extremely lonely Claire catches him, then asks him to have a drink with her. And they start talking. And then there’s more talking. And then there’s more talking. The talking goes on for a really long time. And because of all that talking that’s going nowhere, the scene loses steam. If you’re going to write long dialogue scenes like this, you need to look for ways to keep the tension. For example, what we could’ve done is had Sanjay’s boss tell him he had to be back within 30 minutes, which is barely enough time to complete the task. Then, when Claire catches him, she tells him, “Don’t worry, I won’t tell on you. If you have a drink with me.” Now Sanjay’s stuck between a rock and a hard place. He has to get back to his boss ASAP. And he has to somehow get Claire to let him leave without ratting on him. Without tension, long dialogue scenes die a sad pitiful death. If you watch any of the master’s long dialogue scenes (Tarantino) you’ll see that all of the best ones are laced with tension. And the few that aren’t, are tension-less.