They attached, they waffled, they attached again, they waffled, and now, finally, Leo and Martin are back together again with The Wolf Of Wall Street.

A day off for me but this review is pretty darn good, so I don’t feel so bad. I actually read the book “The Wolf Of Wall Street” a long time ago and thought to myself, “They’ll never make a movie out of this. The main character is the most despicable human being ever.” Though I guess since Scorsese makes tragedies, that doesn’t matter as much. Still, I’m curious as to how he’ll keep us invested in what has to be the single most evil most disgusting flesh-container ever recorded in written form. I also want to know when Scorsese and Dicaprio are getting married. I mean, put on a ring on it already! Here’s guest reviewer Daniel Holmes to report on the script and potential nuptials.

Genre: Biopic

Premise: (from IMDB) Based on a true story, a New York stockbroker refuses to cooperate in a large securities fraud case involving corruption on Wall Street, corporate banking world and mob infiltration.

About: This script landed on the Black List all the way back in 2008 I believe. This is *that* draft. The script has since been through, I presume, many iterations, with Scorsese and Dicaprio flirting with it on and off, until they finally committed to it recently, off a newer draft.

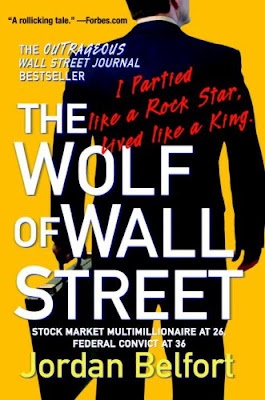

Writer: Terence Winter (based on the book by Jordan Belfort)

Details: 127 pages – first revision, March 4th, 2008 draft.

As a big Scorsese fan, I was excited when The Wolf of Wall Street was first announced. The subject matter seemed like perfect Scorsese material, and with a script written by Terrence Winter (writer/executive producer for “The Sopranos”, creator of “Boardwalk Empire”), I was immediately on-board. The project seemed like a perfect opportunity for a strong return to the Crime genre for Scorsese, and its refusal to die amongst his pile of potential next gigs implied that there might be something special here. But as I learned from Scorsese & Dicaprio’s last collaboration, not even Scorsese can make a great film from a mediocre script. I was cautiously optimistic on whether or not Winter’s script would deliver the goods.

The script opens up with an unmistakably Scorsesean device: a scene that takes place late in the story. Jordan Belfort is the head honcho at Stratton Oakmont, one of the most profitable firms on Wall Street. Jordan and his 700+ minions (most in their early 20s) praise him like a god and they celebrate their success in a scene of such debauchery it would make Gene Simmons blush. Soon after, we see Jordan’s mug-shot taken before being sent back to the beginning to see everything that ultimately led him to this point in his life.

Jordan’s love affair with the almighty dollar has been life long. At 11, he’s collecting nickel deposit bottles and by 16, he’s running his own Italian ice business. He eventually marries a local girl, Denise, whose uncle hooks him up with a trainee job at a brokerage firm on Wall Street. Jordan bonds with Danny, one of the brokers, and Danny takes him under his wing, showing him all the ins and outs of Wall Street (Example: “Fuck the clients. The only responsibility you have is to put meat on the table.”). Jordan is immediately hooked and trains to become a broker himself.

He’s on the road to glory until he arrives for his first official day as a broker on the most unfortunate of days to do so: Black Monday, where the stock market experiences its highest one day drop since 1929. The firm closes down, and Jordan is back at square one. While this incident would send every sane person running as far away from the stock market as possible, Jordan is not like the rest of us. Dirt poor, he soon finds a position at Investor’s Center, a penny stock brokerage which is every bit as bleak as it sounds. However, once Jordan brings his Wall Street savvy ways to the equation, he starts pocketing up to 94 grand a month. He gets Danny in on the mix and soon they open up their own firm. The only problem with Jordan’s success is that it more or less relies on him lying to investors about the shoddy companies he’s pushing them. And since rich people don’t buy penny stocks, all of his oblivious clients are already on the wrong side of the economic spectrum.

Soon, Jordan figures out the key to getting rich people to invest in his penny stocks and so begins Jordansanity, a manic ascent to the top of Wall Street littered with hookers, cocaine, and quaaludes. Jordan gets introduced to Nadine, the most beautiful creature he’s ever laid his eyes on. Naturally, Jordan needs to have her and does so despite his marriage to the loyal Denise, which was otherwise still going strong. Denise inevitably finds out about the affair and Jordan goes on to marry Nadine, and not before throwing a $2 million bachelor party in Vegas.

Everyone wants to be in the Jordan Belfort business, no matter what side of the law they’re on. Everyone, that is, except for Greg Coleman, a pushy FBI agent. Coleman knows Jordan’s up to something, and he won’t be bought no matter how hard Jordan tries. Jordan now has to navigate the rocky terrain of a failing second marriage, drug addiction, sex addiction, and possible jail time all while trying to stay on top.

The Wolf of Wall Street shares a laundry list of similarities with some of the main staples of the Scorsese filmography including: starting the film with a scene that takes place late in the story, a married male protagonist who falls for another woman (who is more often than not blonde), protagonist voice-over, the protagonist’s best friend betraying him, etc. It’s impossible to imagine any scenario where Winter didn’t write this script specifically with Scorsese in mind. Despite this, I’m happy to say that there is just enough freshness in this script for it not to feel like Scorsese will be completely ripping himself off.

For one thing, the character of Jordan is more complex than protagonists cut from a similar cloth usually are. Unlike most of the Henry Hills of the world, Jordan’s morality has somewhat of a grey area. With many similar stories, the protagonist’s sense of morality is either backwards or non-existent altogether. Pathologically, they believe the rules don’t apply to them and they spend their entire lives breaking them recklessly without any sense of remorse. It’s how 95% of criminals are portrayed on film. What made Jordan interesting is that there’s a part of him (however small) that knows he’s doing something wrong and feels bad about it. When he initially stumbles on to his penny-stock scheme, part of what leads him to going after richer investors is simply to avoid screwing over poor ones.

Jordan is no angel by any stretch of the imagination, but his sense of guilt was just enough to keep him fresh in the pantheon of on-screen criminals. Throughout the script, Winter also employed what I call “empathy checkpoints”, where every now and then Jordan either does something or says something empathetic enough to keep the reader within arm’s reach no matter how bad his behavior gets. An example is when he’s presented with the option of ratting out his associates or sending Denise to jail. Despite their marriage having been over for years, he immediately spends the next six hours writing a list of just about every single person he’s crossed paths with throughout his work life.

The other thing I liked about Jordan is that his problem goes much deeper than the fact that he’s greedy. The seed of Jordan’s success and everything that comes after it is pure addiction. Jordan is addicted to drugs, to money, and to sex but his primary addiction first and foremost is to success. All of Jordan’s other addictions ultimately stem from his addiction to success. When Jordan first meets Nadine, he needs to have her. It doesn’t matter that he’s still in love with Denise, or that he’s racked by guilt during his first date with Nadine. Love is no match for the strength of Jordan’s addictive needs.

Another one of the things I really liked about this script was how cinematically it was written. This is one of the few scripts I’ve read in a while that truly always remind the reader that they’re reading a movie. A great example is a scene where Jordan is teaching the employees of his firm his new method for selling. The scene starts off by him explaining the process to a large group of his brokers. As the scene progresses, we cut between brokers applying the methods until we see each one of them having mastered Jordan’s technique having applied it verbatim. The pacing of the scene is impeccable and it’s a great way of visually explaining Jordan’s power and his ability to lead.

Despite the fact that The Wolf of Wall Street hits a lot of familiar beats, I think there’s enough here to bring something relatively fresh to the Crime genre. Regardless, I think the familiar aspects of the script remind one not to fix something that’s not broken. I know Winter’s tackled at least one other rewrite of this script since this draft, so it will be interesting to see how much gets changed.

[ ] Wait for the rewrite

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I Learned: Always pace your script in the way most appropriate to the story you’re trying to tell. This script is a testament to the strength of proper pacing and utilizing it to build a reader experience that reflects the energy of the story. The pure kineticism of the majority of this script harkens back to one film in particular: Goodfellas. One of Goodfellas’ biggest strengths was its pacing and how every single scene was structured in a way that appropriately reflected the story events at that time. The most famous example being the depiction of Henry’s cocaine use as his paranoia hits new heights late in the film. More than anything else, The Wolf of Wall Street is a story about addiction, and the pacing of the script lends itself so well to bringing the reader along with Jordan to experience that ride of constant rushes.