Today’s script is Steven Spielberg’s classic, “Duel,” meets Falling Down.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: A young woman driving her son to school gets into a road rage incident with a man who killed his ex-wife earlier that morning.

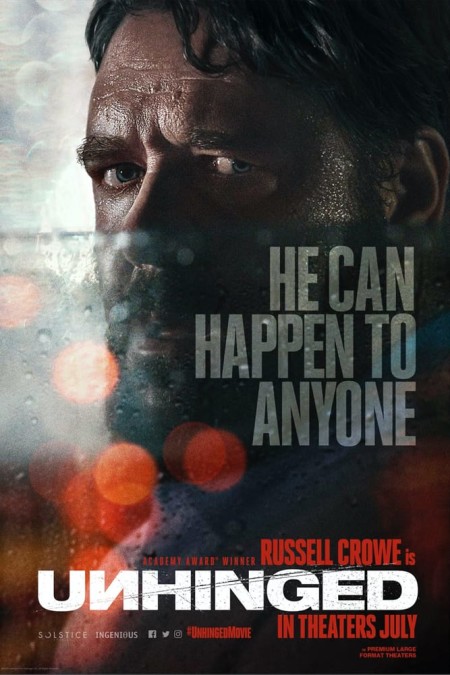

About: Unhinged, starring Russell Crowe, was originally slated to come out this fall. It is the only movie during all of this craziness that has been MOVED UP in the schedule, and will now come out July 1st. Screenwriter Carl Ellsworth is best known for Red Eye and Disturbia. He is also one of the many writers who’s taken a shot at Gremlins 3.

Writer: Carl Ellsworth

Details: 100 pages

You know the pandemic’s getting to you when you’re eagerly checking your promotions folder in your e-mail.

Today I want to talk about a common mistake I see screenwriters make, which is to explore issues in an on-the-nose manner. For example, let’s say you’re upset with how divided the country is politically and how it’s creating a lot of anger on both sides.

The wrong thing to do, then, would be to write a movie about politics and people getting angry about politics. It’s not going to land. It’s on-the-nose.

The better approach is to figure out what’s at the core of the issue you want to explore and write a movie that tackles that thematically. So with the political divide, it’s resulting in a lot of anger on both sides. Therefore, you’d want to write a movie about ANGER. You can pick from dozens of different topics where anger is involved. But the important thing is that the concept explore anger in a powerful way.

That’s what Carl Ellsworth did. This is not a political movie by any stretch. But it’s about anger. Therefore, a lot of people are going to be able to resonate with these characters.

Unhinged begins with a 50-something guy in his pickup outside of what, we presume to be, his house. The dude just looks angry. A few clues point us in the direction that his wife, who he’s in the middle of a divorce with, is in this house. We then see the man go inside. We hear a fight. The man comes back out a few minutes later, blood-smeared clothing. And the house slowly begins to burn.

Cut to Rachel Flynn, in her 30s, single mom, also in the middle of a divorce. She’s taking her son, Kyle, to school and she’s late. We get the sense that Rachel is always late. And that it’s usually her fault. Although you wouldn’t know that if you talked to Rachel. To her, it’s “the world’s” fault. Not the fact that she slept in an extra half-hour this morning.

Rachel pulls up to a red light, needing to take a right ASAP, but there’s a car in front of her. If we’re paying attention, we notice this car is familiar. Wait a minute. Is that the pickup our angry man was in earlier? With cross-traffic clear, Rachel is FURIOUS that the pick-up doesn’t take a right and lays on the horn – BEEEEEEEEEEEP.

Oh. Poor poor Rachel. That was a baaaaaad move.

She angrily whips around the truck and guns a right turn. But it’s rush hour. So it’s only a hundred feet before she’s behind more traffic. And, oh yeah, that pickup guy? He’s now next to her, motioning to Kyle to roll down the window. He’s got a smile on his face so Kyle obliges, and the man kindly tells Rachel that it looks like she’s having a rough day and, therefore, he understands why she honked at him back there.

All he wants is an apology.

But Rachel has too much pride and too much anger to offer an apology. And that just ensured this was going to be the worst day of her life.

The man, who’s never given a name, makes it his mission to follow Rachel around and terrorize her. But not just in his car. He manages to get a hold of Rachel’s phone (early on when she thinks she’s lost him and needs gas, he jacks her phone while she’s inside paying) and starts visiting her most precious contacts, taking them out one by one.

The scariest thing about this man is that he doesn’t care. He’s already accepted that this is his last day on earth. And that makes him very dangerous. He is going to teach Rachel a lesson she won’t forget for the rest of her life. To be a little more mindful of others and show some kindess, even in your worst moments.

This script started out FIRE.

Literally.

The man sets his ex-wife’s house on fire after he kills her.

And for half a script, I’d put this at an [x] impressive. There was a key moment at the midpoint which I thought was a bad choice that negatively impacted the rest of the script. I’ll get to that in a minute. But first, there’s a lot to celebrate here.

I have to give props to Ellsworth for picking this subject matter. This is one of those ideas you read and you say, “OH MY GOD. WHY DIDN’T I THINK OF THAT??” It’s so obviously a movie. Road Rage. There’s never been a movie about road rage based in the city.

There’s Duel, which was highway road rage. JJ Abram’s Joyride, another rural road rage movie. But there’s never been a city road rage movie despite the fact that it’s one of the most relatable things out there. So how nobody’s thought to write this movie before, I don’t know.

There’s also a key moment early in the script where I knew it was going to work. And I talk about this all the time. This is the thing readers look for. That early moment that hooks them, that lets them know this is going to be a little more thoughtful than the average execution of this idea.

It occurs after Rachel drives around the man and speeds off, only to have the man catch up to her and tell the son to roll down the window. Now in 99% of the theoretical scripts I’d read covering this scenario, they would have had the man act crazed or psychotic.

Ellsworth makes an unexpected choice though. The man is nice. He’s smiling. And he’s genuinely prepared to let this go. He kindly asks Rachel to apologize. It was a small moment. But the choice was just unexpected enough to draw me in. I thought, “Hmm, okay. This is not your typical bad guy. He’s got some complexity to him.”

The next moment that pulled me in was when Rachel goes to the gas station. For those of you thinking she would’ve gone straight to the police already, keep in mind, this is early on. She’s only had the one encounter with him and she thinks she’s ditched him.

While she’s inside, he steals her phone from her car. The reason I liked this choice so much is that it allowed for a second series of scenes to occur outside of car-chasing. Cause if the whole movie is him following her around in his car, that’s going to get monotonous fast.

Once he has her phone, he can start checking her e-mails, her texts, and begin infiltrating the lives of the people Rachel knows. For example, he finds out from some texts that Rachel is supposed to meet her divorce lawyer at 9. We know how this guy feels about divorce lawyers so he goes there under the pretense that he’s a friend of Rachel’s.

All of that was fun.

But there was a key moment at the midpoint where the script lost some steam. The man calls Rachel (he left a phone in her car) and they kind of unload the difficulties of their lives on each other. And the reason I didn’t like that was because a character like The Man only works if he’s mostly mysterious. The more we know about him, the less scary he becomes. And if he’s connecting with Rachel and understanding her anger, on a certain level, that takes away from the engine driving the script, which is him making her pay for what she did earlier.

From that point on, the script lost something. And you can go right back to the grandfather of this genre – Duel – to see that, yes, the best way to make that person scary is to not tell us a whole lot about them. All we needed to know about this guy was that his ex-wife left him and destroyed him in the divorce. THAT’S IT. From there just make him scary. That’s it.

Despite that hiccup, this was a good idea for a script and the execution was pretty darned snappy. For those frustrated at being kept inside all this time, Unhinged should offer a nice release.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Don’t use camera directions on the page (i.e. “CAMERA PANS UP TO SEE THE ENTIRE ALLEYWAY”). You’re not the director. You’re the writer. However, there are ways to get around this. You simply imply where the camera is going to be. Here is a line of description from that first scene where the man kills his wife: “We STAY INSIDE THE CAR and watch through the windshield as the Man heads ominously toward the house, passing by a FOR SALE SIGN now planted in the front yard.” Without ever saying “camera” or using technical terminology, we understand where the camera is. You don’t want to do this all the time, cause it’s still directing. But you can throw these lines in there every once in a while and get away with it.