Genre: Sci-Fi/Drama/Thriller

Premise: (from Black List ) In the year 2065, a fiery teenager with a wild imagination, her paraplegic mom, and their clueless robot struggle to navigate the post-apocalypse; but when the mother’s wheelchair breaks, the trio must venture out into the dangerous “outside” for a chance to survive.

About: Today’s script finished with 11 votes on last year’s “best scripts of the year” Black List. Screenwriter Kryzz Gautier has written and directed a lot of short films. Her biggest credit up to this point is writing the Bioshock 4 video game.

Writer: Kryzz Gautier

Details: 114 pages

We’re going BACK to the Black List. This time for a little first act introspection. Today’s script takes on all of the challenges we’ve discussed about first acts and because the writer seems new to the medium, things get messy. But that’s okay because we’re all just trying to get better here. So let’s take a look!

Wheels Come Off follows 16 year old, Manoella Cortez, who lives in a city I can only assume is New York, a couple of decades after some massive catastrophic event has left the city in shambles.

Manoella spends most of her days with her 2 foot tall robot, Tony, scavenging apartments for food. Sometimes this means stealing from the dead. Sometimes it means stealing from the living. Which Manoella doesn’t feel bad about because she’s got to support her wheelchair-bound mother, Carla.

But when they run out of food, the two must go into the city together to try and accomplish a major food score. Unfortunately, they steal from the leader of a gang, Erick, who makes it his mission to find and kill both mother and daughter (and robot).

Along the way, our heroes meet up with a group of disadvantaged people (one has cerebral palsy, one is deaf, one is blind, etc.) and Manoella falls in love with their leader, a young woman named Ari.

But when Carla’s health deteriorates due to an injury, they must locate the last person she wants to speak to, Manoella’s father, who ran the robot company that may have caused the apocalypse. The extent to which Manoella cares for Carla will be put to the ultimate test when evil Erick figures out where they’re going and is determined to stop them.

Okay, let’s talk about what I liked here. I like that this is based on real life. Kryzz says on the title page that this script is inspired by her real life struggles while taking care of her disabled mother. It’s some of the oldest, yet, most valuable, writing advice you’ll hear: Write what you know. Because when you write what you know, you write specifically. “Specific” is the opposite of “general” which means you avoid writing a generic story.

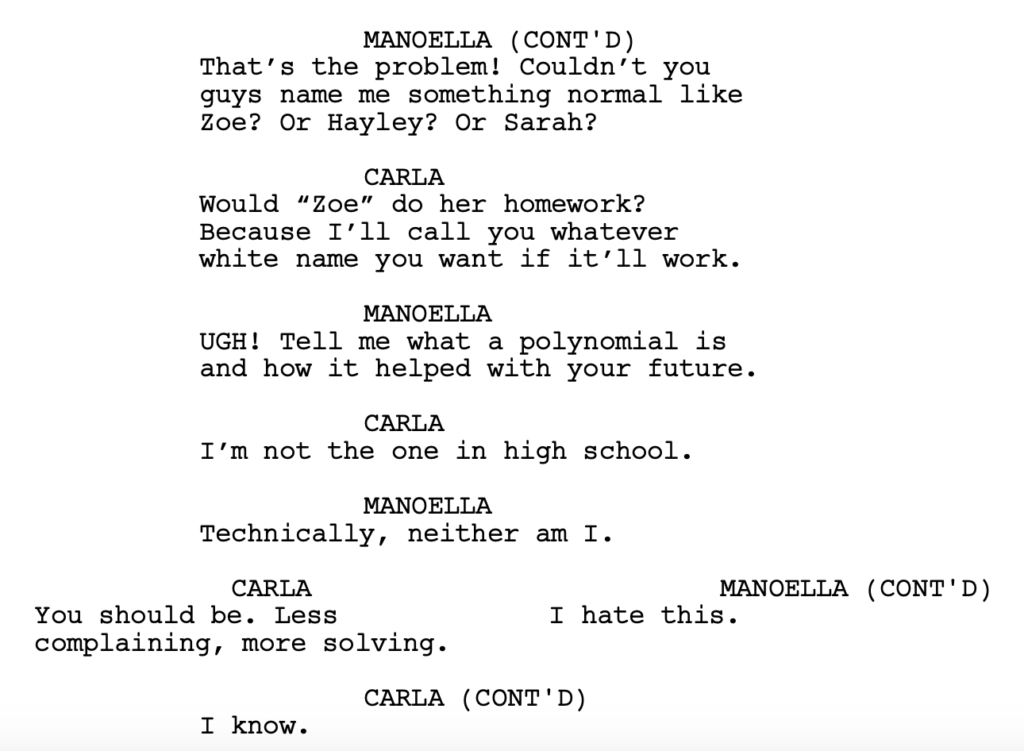

I also liked the choice to make Manoella and Carla outsized personalities. Both of them were opinionated and talked a lot, which meant a lot of their dialogue was packed with energy.

I also felt that, once Kryzz got out of the first act, the script became way more relaxed and free-flowing, which made the pages easier to read.

And that’s where I want to focus today’s review because the weakest part of the script, by far, is the first act. And since we’re talking about first acts this month, it’s a good first act to dissect. The combination of setting everything up as well as not understanding the screenwriting medium made for a bumpy ride that, if I wasn’t reviewing this script, I would’ve checked out by page 10.

Let’s start with the first line of action:

“A pair of legs sneak past wheels then exit an apartment.”

Take a hard look at this line because there’s something wrong with it. See if you can tell me what it is.

Did you figure it out?

The most important detail in the line is left out. What do the legs look like? Are they muscular? Thin? Long? Stubby? Hairy? Smooth? A man’s legs? A woman’s? Old? Young? Any one of those adjectives would’ve given us a much better feel for what was happening. But those details were left out. And this is a common occurrence with beginner screenwriters. The writer assumes the reader can read their mind.

We don’t know what’s in your head unless you tell us.

I must’ve given this advice five times this month on script consultations. Writers continue to think the reader can read their mind. I’m not saying you have to detail everything. I’m saying whatever the most important elements in a scene are, you need to detail those.

Think about it this way. The people watching this movie will be able to answer that question right? They’ll know whether the legs are muscular, thin, long, stubby, hairy, smooth, a man’s, or a woman’s. So why does the reader not get this information? The point of a screenplay is to detail what people are going to see on the screen.

What’s so ironic about this mistake is that it’s the opposite of the writer’s other major mistake in the first act, which is that everything is overwritten. We routinely run into 8 line paragraphs (Try to stay at 3 or less). And there’s a lot of description detailing the same things over and over again (that Manoella steals things from apartments).

We don’t get to the inciting incident until page 28, when Erick catches Manoella stealing a robot battery from his place and vows to kill her and her mom. As we’ve learned this week, you want your inciting incident to happen between pages 12-15 if possible.

Now this is where things get interesting because I suspect Kryzz might push back and say her inciting incident was when Manoella and her mom realize they’re running out of food and have to go find more.

An inciting incident, to me, is an event that is big and has major consequences. I don’t buy that having four days left of food when you’ve already proven to be good at finding food to be a big event with major consequences. I do consider the most dangerous person in the city vowing to kill you a big event with major consequences.

Waiting that long to introduce the story’s most important plot point puts you in a bind because it means you’re setting up character and world for the 27 pages that precede it. And while that may be great for you, the writer, since you have alllllll this space to casually set up your world, it’s terrible for the reader, who is impatiently waiting for the cool stuff to happen.

One of the reasons we stick to these stringent page checkmarks is because it forces you to set up your story faster than you want to. I know that sounds like a bad thing but it’s actually a good thing. Because when you have to set up something in a short amount of time, you think about what’s necessary and what isn’t.

I’ve said this a million times but what makes the pros so much better than the amateurs is that they can do what you do, but in half the pages. Cause anybody can set up a world with enough time. It’s the pros who figure out how to do it quickly and still be effective.

That’s a big part of what writing first acts is. It’s consolidating a bunch of information into a less-than-optimal amount of scenes, and somehow still doing it effectively and entertainingly.

If I’m being 100% honest, Wheels Come Off feels like a script that, five years ago, agents would’ve said, “You’re not ready yet.” There are too many beginner tells (oversized paragraphs, music cues, dream sequences, dual-line dialogue). But I guess now the Black List is prioritizing certain things over script quality that are propping these scripts up and it’s confusing to aspiring writers who have been told that a lot of this stuff isn’t okay.

It’s not that the script is bad. It’s actually quite heartfelt in places. But it reads no different than any of the Amateur Showdown scripts we’ve seen on the site. So I can’t endorse the script. Like almost all of the 2021 Black List scripts I’ve read, it’s messy. It doesn’t feel like the writer has a good grasp on the craft yet.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: For those who don’t understand why dream sequences are frowned upon in screenwriting, dream sequences are great for directing and actual production. They allow the director to create striking stylized sequences that are fun to look at. But on the page, all these sequences do is fill up space with words and, at worst, feel pretentious. We can’t see the striking images nor hear the intense soundtrack that make these scenes work. I’m not saying never use them. But in a perfect world, you’d keep them out of your spec script and then, when you get hired for the actual movie, put them in there.