The secret to writing a great screenplay with the least amount of effort.

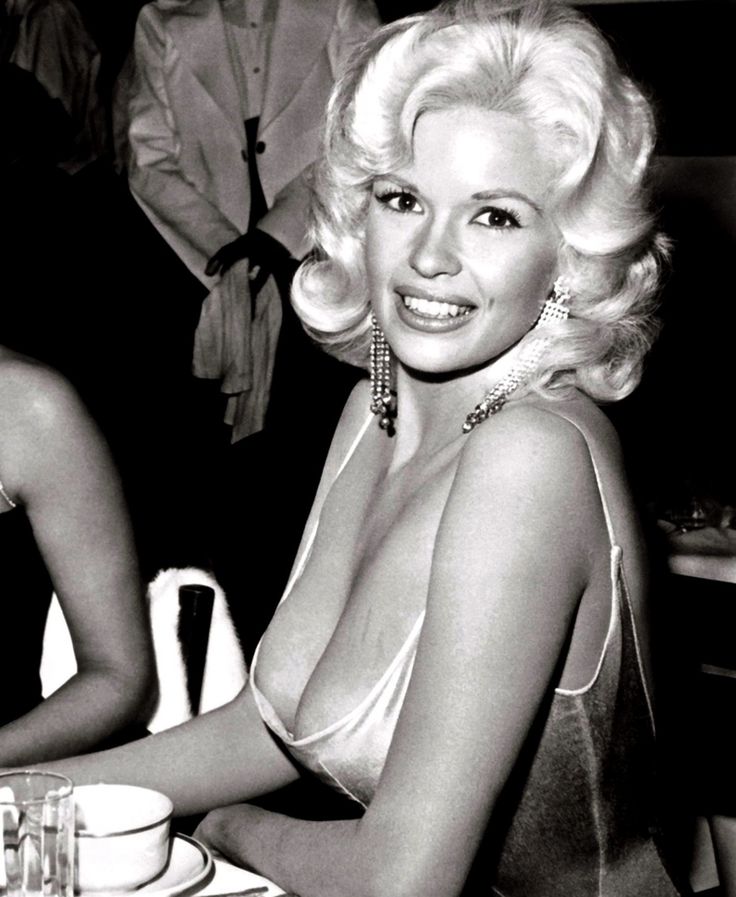

Jayne Mansfield, star of the 1963 film, “Promises Promises”

Jayne Mansfield, star of the 1963 film, “Promises Promises”

I’m always thinking of new ways to crack the screenwriting code. Screenwriting is funny in that, at its core, it’s simple. Write a story with a beginning, middle, and end. Make sure it’s interesting. Voila. That’s it!

But like any skill, in order to attain mastery, it can get quite complex. I still remember when my first screenwriting teacher told me that each scene needed to achieve five different things. Pretty sure, in that moment, my brain short-circuited.

What happens to most screenwriters is that they start off believing in the former – that screenwriting is easy. They’ve seen movies. They know what movies they like and don’t like, so they figure they’ll write movies similar to what they like and that’s all you need in order to be a good screenwriter.

What happens to the majority of these writers is that their scripts don’t get any success or recognition and they figure that the system is rigged, probably to reward nepotism, so they peace out, never to write another screenplay again. Many of the remaining screenwriters become obsessed with cracking the code and, over the years, delve into the most minute details of the craft, figuring that if they learn EVERYTHING, they’ll be able to write a great script.

Most of these writers never return from that dark place. They just go deeper and deeper into the minutia, looking for the meaning of it all. I’m here to tell you that if you get trapped in that place, it’s just as hard to write a good script there as if you’re a beginner and think writing is easy. Down there, you’re writing from a place of technicality, which is hard to build a moving impactful story around.

Now let me be clear. I’m not saying all technical thought is wrong. There’s a mathematical element to screenwriting that cannot be ignored. The fact that you have to keep your story between 100-120 pages alone means you have to be strategic about how you plot, how you approach your character arcs, where you place your setups and payoffs. But we never want that aspect of your writing to impede upon the ultimate goal. Which is to write a great story.

Today’s article was born out of my newsletter article (sign up if you haven’t already: carsonreeves1@gmail.com) where I discussed “story engines.” This is the same idea but I wanted to make it even simpler for you. In fact, I would say this is the simplest strategy to create a good story. You don’t have to learn any technical terms. You don’t even have to know how to structure a script. As long as you follow this one rule, you can write a good screenplay.

Want to know what it is?

Promise.

No, that’s it. A promise.

All writing is is a promise. You extend a promise to the reader that if they keep reading, they will be rewarded.

Think about it.

Barbie is dancing at the beginning of Barbie, living her best life, when she freezes and asks everyone, “Does anybody else here ever think about dying?” That’s a promise. It’s a promise because we now want to find out why Barbie is having these thoughts. To prove why this promise works, imagine if Barbie had never vocalized these thoughts. She just goes about her perfect day and then goes to sleep. Why should we keep reading?

Promises can be big. They can be small. As long as there is at least one compelling promise in play at every stage of your story, the reader WILL TURN THE PAGE. Let me say that again. As long as at any point in your story there is a compelling promise that has been made, the reader will want to find out what happens next.

What does a bad promise look like? “Here’s a funny character.” That’s not a promise. The character may be funny to you but who knows if it’s funny to others. So we might not want to see any more of them. Remember, the key to the “promise” strategy is that we want to turn the page. If the promise isn’t good enough for that, the strategy won’t work.

So what are some actionable promises to keep the reader reading?

A dead body – This is one of the strongest promises you can make because who doesn’t want to find out who killed this person? Or why?

Will these two people get together? – We were talking about this in the story engine article. One of the early promises in Killers of the Flower Moon was, “If you keep watching, you’ll get to find out if these two get together or not.” This is one of the most often-used promises in the trade.

Will these two people resolve their issues? – This is popular in the team-up genre. Two characters who don’t get along are forced to team up with one another. The promise is that if you keep watching, you get to find out if they eventually find peace with one another.

Promises can be more immediate as well. And should be, depending on the situation. Early on in screenplays, the reader’s attention span is shorter. So you should be looking to introduce promises that have quicker resolutions.

A trained killer gets locked in a room with a group of thugs (The Equalizer). The dramatic irony is through the roof here (we know the thugs are in a lot of trouble) so the promise is strong. We can’t wait for him to kick their a$$. How do I know this promise is effective? Because I know every single one of you reading this right now would turn the page to find out what The Equalizer does to those thugs.

One of the most powerful promises is a strong mystery. I was just watching the pilot episode for the show, A Murder At the End of the World. Early on, we see a couple discover a dead body and then (spoiler) the killer catches them in the act, raises his gun to shoot, but before we show what happens, we cut to the present day. We know one half of the couple, the girl, is still alive, since she’s talking to us. But there’s no mention of what happened to the boyfriend. Was he shot that day? That’s a promise that the writer is making to you. “If you keep reading, I will answer that question.”

Later still in the episode, a man shows up at the woman’s door and says that she’s invited to meet one of the richest men in the world. Another promise. If you keep reading, you get to find out who this man is and why he’s inviting her.

You should have multiple promises going on at all times. They shouldn’t all be giant promises (a girl is possessed, a billionaire is murdered, a man is still in love with his girlfriend after spending 42.6 years in cryogenic stasis) or the promises will compete against each other. But you should be injecting smaller promises on top of your larger promises. I call this “layering.” Because you want the reader to stay engaged in the short term. So you make these immediate promises (The Equalizer just got locked in this room with these thugs. I promise you that if you keep reading, I’ll let you know what happens within the next two pages).

Just like all of writing, there is subjectivity involved in how compelling a promise is. You may think I want to learn more about how all this plastic got into this whale’s stomach, but you’d be wrong. So you’re always gambling in that sense. Which is why you want to lean into the types of promises that have proven to work over time.

Compelling mysteries, whodunits, will-they-or-won’t-they-get-together, unresolved relationships, a loved one has been kidnapped.

Here are some promises from popular movies throughout the years:

An alien is after me: No One Will Save You

Bank robbing brothers are trying to stay one step ahead of sheriffs: Hell or High Water

A giant shark is terrorizing the beach, killing everything in its path: Jaws

A dangerous violent man is coming unhinged: Joker

A man is erased from existence and sees what the world is like without him: It’s A Wonderful Life

People are stuck in a dangerous video game: Jumanji.

In each of these stories, a giant promise is made that makes it nearly impossible for us not to want to keep reading. Now, of course, you do have to write compelling characters for this strategy to work. But if you can do that, you can basically keep a story going forever. And if you think that’s not true, let me point you to Marvel, to Fast and Furious, to Star Wars, to your favorite TV show. Those stories go on and on and on without any real end because the writers keep making compelling promises. Marvel does so at the end of every movie with their post-credit scenes. Now you can do the same. And reap the rewards from doing so. :)

Hey! You want to get a screenplay consultation from me? You should! I’ve read over 10,000 screenplays. I’ve seen every trick in the book. If there’s anyone who can help you turn your screenplay into the masterpiece you and I both know it can be, it’s me. And if you mention this article, I will take 40% off my pilot script or feature screenplay rate. Just e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com!