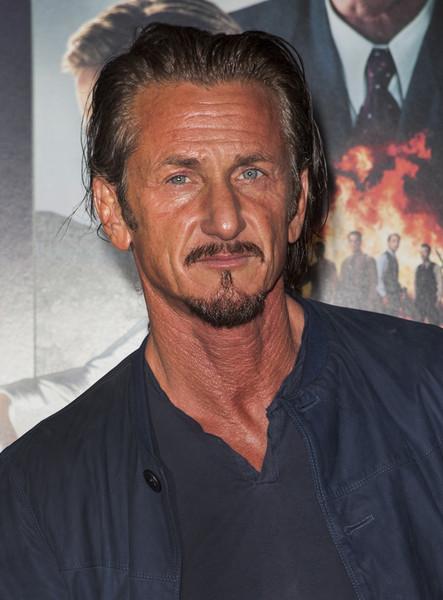

My new best friend Sean and I are hanging out later. So I just wanted to post a picture of him.

My new best friend Sean and I are hanging out later. So I just wanted to post a picture of him.

One of the most frustrating things about going through all these scenes was reading scenes that just didn’t go anywhere. Nothing was happening. And here’s where you see a major difference between experienced screenwriters and new screenwriters. It’s the difference in their interpretation of the phrase “something happens.” In a script, in every single scene, in order to keep a reader riveted, something NEEDS TO HAPPEN. Beginner writers say, “Hey, that conversation between me and my co-worker about our douchey boss was kind of funny. I’ll put that in a script.” And they do. And they don’t understand why no one responds to it. It was cute. There were a few funny lines. And it was life, man! Real-world shit! The reason nobody cared is because nothing happened.

Experienced writers know that “something happens” means ratcheting up the stakes and bringing something big to the table, a scene where what people say actually matters, where there are consequences to people’s actions! If they’re going to write a scene about two co-workers, one of them is going to have a gun hidden in her jacket. She and her co-worker had an affair. He’s broken it off. She’s been e-mailing and texting and calling him to no avail. He barely responds to her. Echoes of Fatal Attraction. She’s finally convinced him to have lunch with her. She’s brought a gun to their little chit-chat and is considering using it if the conversation doesn’t go well. Now, something is happening.

There’s an old saying with writing screenplays. It goes something like this: Your story should be about the most important thing that’s ever happened to your character in his life. In other words, if what you’re writing about isn’t even the biggest thing that’s happened to your hero, why do you think we would be entertained by it? I think you can apply this approach, at least partially, to scene-writing. The scenes you write should be the biggest 1, 2, or 3 things that happened to your character that day. There will be exceptions to this for sure. But if you’re picking your best scene in the whole script? One that really shows off your chops? And it doesn’t even seem (or barely seems) like it was the most important thing that happened to your character that day? How do you expect a reader to be impressed?

But here’s the real killer. The writers who WERE able to write a scene where something was “happening?” The ones who avoided that pothole? They often made the mistake of writing the scene in the most predictable way possible. Those are some of the hardest scenes to read. Because here we are. This huge scene is laid out before us (i.e. Hero finally confronts his mother who left him as a child), and it… goes… exactly… according… to plan. He asks mom why she did it. She takes a deep breath. Says she doesn’t know. She thinks about it. Talks about how it was all too much for her. I mean, WE’VE SEEN THAT SCENE BEFORE! We’ve seen it a billion times.

I just don’t understand why screenwriters don’t realize this. Why they don’t realize that we’ve been down that road before. As a writer, it’s your job to know the reader’s expectations, and then go in a different direction. That way you surprise them as opposed to bore them. This to me, is what all the best writers do. And it’s one of the easiest skills to learn. You don’t have to be a master storyteller to do it. All you have to do is recognize the way a scene typically plays out, and go another direction. Even if that direction turns out to be a bad choice, at least we’ll applaud you for not taking the obvious route.

Another thing that shocked me is I don’t think I read a single “Hitchcock bomb under the table” scene out of all the submissions. Someone can correct me if I’m wrong (Miss SS read a few submissions so maybe she did) but I didn’t see one. This is one of the EASIEST ways to write a good scene. You should have 2-3 versions of this scene in every script you write. Maybe more depending on the genre. Essentially the idea is, if you have two people talking at a table, it’s boring. But if you tell the audience there’s a bomb underneath the table, a ticking bomb, then all of a sudden the scene becomes interesting.

This is where Sean and I met. Memories.

This is where Sean and I met. Memories.

You can apply this to a scene in a million different ways. I just did above. The two co-workers talking, one of them secretly has a gun they’re planning on using. That’s a Hitchcock scenario. The scene with John McClane and Hans on the roof in Die Hard. We know he’s the bad guy. John doesn’t. That’s a Hitchcock scenario. A 17 year old girl is going out with a 35 year old biker that nobody in her family likes. There’s a big family dinner. The girl and the guy are planning on dropping the bomb that they’re getting married. That’s a Hitchcock scenario. If you want to win a scene contest, write a good “Hitchcock scenario” scene and, at the very least, you’ll be in the running.

Not every scene has to be a world-beater. Comedy is different. As long as you’re funny, you can get away with not much “happening.” But you have to be a freaking dialogue master to pull that off. You have to write dialogue that SINGS. When you give your script out to people, you better always be receiving the compliments “Your dialogue was great” and “I couldn’t stop laughing.” If not, do not try to rest on your dialogue alone. But to be honest? Why not do both? Why not create those intense pressure cooker situations that make scenes pop ALONG with the comedy? That’s why Meet The Parents was so good. They did such a great job setting up the stakes of that dinner scene. With how much Ben Stiller’s character wanted to impress Robert DeNiro’s character (his girlfriend’s father). They made it clear that everything was riding on his performance at that dinner table. So each word spoken was a potential death trap. Then, when they’re bantering back and forth about whether cats have nipples, it’s not just the writer trying to show you how funny he is. It’s Ben Stiller’s character digging a hole the size of the Grand Canyon trying to find a way out of his continued screw-ups. When we’re emotionally invested in a scenario, we’ll always laugh more.

Despite my passionate plea for better material, this week was really cool for me because I usually read everything within the context of the script. This placed my focus SOLELY on the scene. The scene had to live or die on its own. And it made me realize that each scene, in its own way, is like a script. It’s got its setup, its conflict, and its resolution. It needs goals, stakes, and urgency. It needs conflict. But most of all, it needs to matter. We need something important to be happening or else we’re going to tune out. And you guys need to treat it like that. Treat every scene with pride, like it’s its own story, and try to write the best story you possibly can. If you do that, the next time I hold one of these contests, you won’t have to choose a scene from your script. Because every one of them will be great.