What is anchoring and why is it important?

Let me start off by saying that anchoring is an advanced writing technique that beginners shouldn’t worry about yet. If you’re a beginner, worry about structure, keeping your descriptions succinct, getting your scenes down to a manageable length (under 2 and a half pages), not writing on-the-nose dialogue, arcing your characters. Anchoring is not going to help you if your fundamentals are so bad that your script is unreadable.

But once you’ve got all that down, anchoring can help you take your screenwriting to the next level. What is anchoring?

Anchoring is the process by which you anchor characters, plot points, story beats, and other story choices to REAL LIFE EXPERIENCE.

A common critique you hear a lot of writing teachers use is that there’s no “TRUTH” to a character (or to a moment). What they mean by this is that the character feels “written,” they don’t feel “true-to-life.” And that’s because, most likely, you completely made them up.

“But Carson, isn’t that the point of writing? To make stuff up?”

Yes and no. You want to make things up that give the reader a great reading experience. But that doesn’t work unless the reader BELIEVES what’s happening on the page. And to make them believe, your story must feel as real as possible (relative to the genre and movie type you’ve written).

This is where anchoring comes in. Let’s say you’re writing a comedy script. Your main character is the straight guy and you want to add a “zany best friend character.” If you construct that character completely out of thin air, he’s not going to work. He’ll feel made-up, cliche, thin, you name it. However, if you had, say, a crazy roommate in college, and you based your zany best friend on that roommate, now that character is going to carry a truth, a “realness” to him or her. Why? Because they’re based on a real person! This is anchoring.

Anchoring isn’t limited to character creation. Anchoring applies to any situation you write into your script. For example, if your characters have to go to a big company event, but you yourself have never been to a company event, you need to find a way to anchor that. Maybe you once attended a giant wedding. Weddings tend to have crossover with corporate events as both include a meal, socializing, music, drinking, etc.

What you’re looking for is specific stuff you can pull from the wedding to use at the company event. For example, maybe you remembered an annoying mariachi band that kept coming around and playing when no one wanted them to. Or maybe you ordered a drink at the bar only to learn that you had to pay for it. Maybe the planners messed up and didn’t include enough tables, forcing you to eat dinner while standing up.

Specificity sells realism and anchoring is a great way to add specificity.

I’ve discovered that there are five main levels to anchoring. Preferably, everything you anchor should be a level 1. But if that’s not available, you’ll have to go further down the list. Just know that for every level you go down, the less realistic your characters or situations will be. So proceed through these lower levels with caution.

LEVEL 1 ANCHORING – PERSONAL LIFE

This shouldn’t be surprising. Ideally, you’d like to anchor as much as you can to your own personal experiences. These are the things that will come off as the most truthful. People will read your stuff and give you compliments like, “It just all seemed so real.” That’s because it was real. A good example of this is Garden State. There was a scene in that movie where Zach’s character is about to get into his car the morning after a long night of partying and sees a ripped-off gas nozzle sticking out of the tank – you don’t just make that stuff up. That either happened to him or someone he knew. Which leads us nicely into Level 2.

LEVEL 2 ANCHORING – FRIENDS AND FAMILY

While not as good as anchoring something to your own life, anchoring stuff to your friends and family’s lives is the next best thing. If you want your hero to work in an office but you’ve never worked an office job in your life, anchor the job to your best friend who works at an office. You may not live their life, but you’re around them enough and heard about their experiences enough that you can craft a pretty solid approximation of the job. Likewise, if you need to write a sex addict into your script and have a friend who’s an alcoholic, you can anchor a lot of your character’s behaviors to your friend’s. That’s an important thing to note about anchoring. It doesn’t have to be exact. If you need to write a teenaged bully into your high school comedy, there’s no law that states you can’t anchor that bully to the Starbucks barista with an attitude you deal with every morning when you buy your coffee.

LEVEL 3 ANCHORING – SECOND HAND STORIES

We’re getting further away from the truth, which means you want to think twice about using this in your script. But occasionally you’ll hear friends, family members, or coworkers tell stories about someone they know or an experience they had, that was interesting in some way. Since you’re a writer, you’ll naturally want to include some of these moments in a screenplay. The problem is these stories are far enough away from personal experience that they contain a dream-like quality to them. They lack the specificity to make them believable. For example, I knew a guy through a friend who used to play on the professional tennis circuit. One night he told me this elaborate story about getting cheated by an umpire at the French Open. It was a great story. And I tried to anchor the essence of the story into a baseball script (with the home plate umpire committing the same sin on a player). But it never quite worked because I didn’t know all the details. I wasn’t there to smell the red clay, to endure the impatient booing of the crowd, to feel the pressure that, if I lost that match, I didn’t have enough money to get a plane back to the U.S. Second hand story anchoring can work. But it’s never going to feel as realistic as Level 1 or 2 anchoring.

LEVEL 4 ANCHORING – MOVIES AND TELEVISION SHOWS

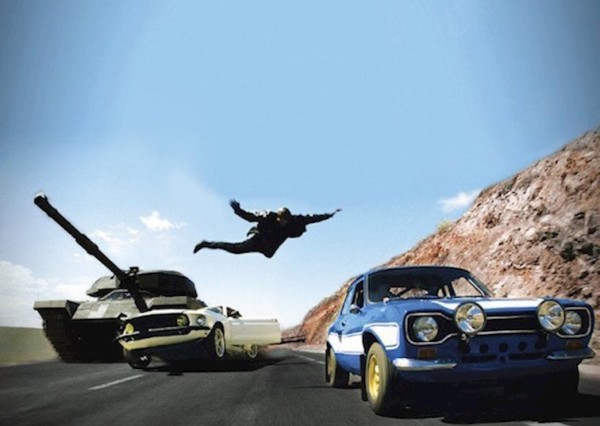

This is where the majority of beginner and intermediate writers anchor their writing – to stuff they’ve seen. Need a villain? Hans from Die Hard worked. I’ll just create another version of him! Need a good chase scene? I loved that chase scene in Fast and the Furious 4. I’ll change the cars from Corvettes to Maseratis and nobody will be the wiser! This is literally the WORST thing you can do when you’re writing a script. It’s why so many amateur screenplays are so bad. The writers are just rewriting what someone else wrote. With that said, anchoring off of other movies can still work if you follow a couple of simple rules. Rule #1 is to twist whatever you’re cribbing enough so that nobody will be able to tie it back to the anchoring source. For example, if you made your “Hans” character a woman and had her use sexuality as a weapon, nobody’s going to be saying, “This is just like Hans from Die Hard!” Rule #2 is to favor movies that are old or unpopular. Quentin Tarantino built much of his career around this. Anchor characters and situations to barely-seen movies and nobody will call you out except for extreme cinephiles.

LEVEL 5 ANCHORING – YOUR IMAGINATION

If you try and craft a character strictly out of your imagination and don’t base them on anything or anyone you know or your friends and family know or who you’ve heard about second-hand or who you’ve seen in other movies, it’s 99.9999% likely that that character is going to feel written. For example, a flea-market furniture maker who fought in Vietnam before becoming a pacifist sounds like a really interesting character on paper. But if you’ve never been to a flea market and you don’t know anyone who’s sold self-made furniture or fought in a war or who’s a pacifist, it’s highly likely that character is going to read as total bullshit. BUT! Maybe you knew a hippy when you first moved to Los Angeles who made and sold jewelry on the Venice Beach strip and maybe your dad’s friend who used to come by for dinner twice a year fought in Vietnam and so if you could somehow combine those characters into one, there’s a shot at making that character work. That’s the power of anchoring.

A couple of final points I want to make. Where non-anchoring hurts you most is when you write a big character or include a big plotline that a lot of people are familiar with, but you know very little about. This makes for a lot of people who can call you on your shit. And they will. For example, if neither you nor anyone you know has kids to parent, yet your movie has a large parenting component, you’re going to get called on it. If you write a cop and the only thing you know about cops is what you’ve seen in movies – called on it. If a 60 year old who doesn’t even know what Instagram is tries to write a teenager – called on it.

When dealing with these issues, the solution may be to ditch the storyline or character you know so little about. Or re-write them into something you know well.

Finally, I’ll address something a lot of you are probably wondering. “What about if you’re writing in a completely imaginary world? Like Star Wars or Harry Potter?” When you’re writing inside of imaginary worlds, the big focus will be on anchoring characters. If they’re believable, everything surrounding them will be as well. For example, you may not know anyone who owns a floating city like Lando Calresian. So how do you write a character like that? Well, maybe you have this one uncle who showed up to every family reunion who was soooooo charming. Yet, if you talked to anyone behind closed doors, they told you he was involved in some shady shit. That’s how you create Lando Calresian. You base him on someone you know. And once we believe in that character, we’ll believe in that big floating city he runs.

I hope this is helpful. Feel free to share your own anchoring experiences in the comments section.

Carson does feature screenplay consultations, TV Pilot Consultations, and logline consultations. Logline consultations go for $25 a piece or 5 for $75. You get a 1-10 rating, a 200-word evaluation, and a rewrite of the logline. All logline consultations come with an 8 hour turnaround. If you’re interested in any sort of consultation package, e-mail Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: CONSULTATION. Don’t start writing a script or sending a script out blind. Let Scriptshadow help you get it in shape first!