We’re going to do something a little different in today’s article. We’re going to talk about the actual PRESENTATION of a screenplay. The way it’s written, the way it looks to a reader on the page. While not as important as story, the choices in how one presents his work can have a big influence on how the reader interprets it. The theme you’ll find here is that while some approaches are preferable to others, every writing choice you make should be made for one reason: it’s the best way to tell the story at that particular moment. With that said, here are some common issues I run into when I read scripts.

CLIPPED WRITING

Clipped writing is something I see a fair amount of. The idea behind this is that traditional writing is too long-winded for screenplays, which require a more “to the point” approach. The problem is, some people have taken this so far that it’s unclear what’s being said. After awhile, the reader starts to feel like they’re reading an illiterate robot. For that reason, this style probably shouldn’t be used outside of special situations. Maybe, for example, a character wakes up at the beginning of the script and is confused. So the confused stutter-pattern of clipped writing helps convey the character’s confusion. There are also times when it works in action sequences. But for the most part, try to write full sentences.

BOLDED SLUGS (or BOLDED UNDERLINED SLUGS)

Bolded slugs (or bolded underline slugs) have become in fashion lately. And to a certain extent, they make sense, as they visually signify a new location or scene, which can be helpful to the reader. Where bolded slugs get annoying is when there are a lot of short scenes or the writer is a slug-lover, so that four times a page, we’re stuck staring at big chunky ugly disruptive lines of text. My suggestion would be this. If you write a lot of long scenes, like, say, Tarantino, you can use bolded slugs. But if you’re constantly jumping from one place to the next, step away from the bold. It’ll shift the reader’s attention away from what really matters, which is the action and the dialogue.

THE ‘GET INSIDE THE CHARACTER’S HEAD’ ACTION LINE

Using your description to tell us what a character is thinking is considered shoddy writing. However, I do see it quite a bit (there was a decent amount of it in “The Fault In Our Stars.”). Where it becomes problematic is when a writer gets carried away with it and starts using it for things we already know. As you can see above, we can tell from the dialogue that Miss Scriptshadow doesn’t want to see X-Men, so using description to tell the reader afterwards feels like overkill. If you want to make sure the reader gets the point, there are other options, like using an action. So you might cut to Miss Scriptshadow’s computer, see that she’s looking at a trailer for “The Other Woman,” longingly, then click it closed with a sigh. I’m telling you: Only use this device sparingly. It can get annoying quickly.

LOVE OF ADVERBS

Forget the dialogue here. Look at the action text. Carson “walks aggressively.” He “angrily opens it.” Adverbs make your writing look weak and indecisive. Instead, try to find a verb that says the same thing. You’ll notice that your sentence all of a sudden looks manly and strong! “Carson barges towards the fridge.” “He whips it open.” Just make sure that you have the right verb for the action. Don’t put in a verb that doesn’t fit just to avoid the adverb. In other words, don’t say Carson “dances over to the fridge” just because I said you had to verb it.

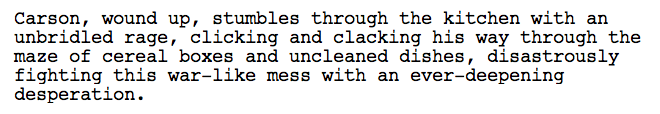

SIMPLIFY YOUR WRITING WHENEVER POSSIBLE

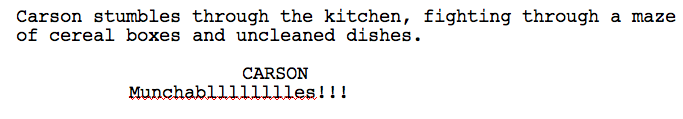

Readers don’t want to have to work for basic information. Screenwriting should be simple and to the point (most novelists will actually tell you the same thing). The above is a really clunky sentence, the kind a man could get lost in and never come back. If I had to read a whole script of that, I’d swallow a box of brads and die by internal bleeding first. To simplify this, focus on two things. First, figure out how to turn useless segments into actions, then figure out what’s redundant or isn’t needed. For example, there’s no need to say “wound up,” since we already know he’s wound up and it interrupts the flow of the sentence anyway. So we’ll drop that. “Clicking and clacking” does add some sound to the scene, but I’m not sure it’s necessary. “Disastrously fighting this war-like mess with an ever-deepening desperation” is redundant. If we really want to convey Carson’s anger, we can add an action, like him shouting in frustration at the end. So the new simpler text would look like this:

I’m not saying you should NEVER offer detail in your writing. You just only do it when it’s important. Like if a detective walks into a crime scene where very specific things will be important to know later on – then go for it – describe away. But a guy looking for munchables? We don’t need to get into any detail with that, unless you’ve got some amazing jokes you can weave into his search (even then, it’s probably not worth it – simplicity should usually win out).

SUBSEQUENT ACTION LINES (NO SPACES IN BETWEEN)

While I can’t speak for everybody, this practice drives me CRAAAA-ZY. I don’t know who came up with it, but the sooner it goes away, the better. First of all, you want to be weary of any writing device that goes against what readers are used to unless you’re positive it makes the script better. The above looks so odd to a reader, they’ll probably stop for a second and wonder if it’s a formatting error before moving on. I’m not even sure of this device’s intention. I just know that it looks and feels odd.

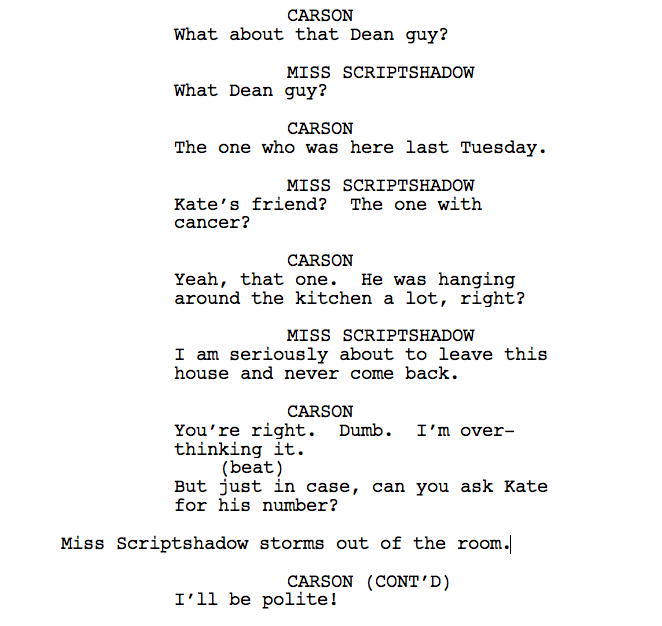

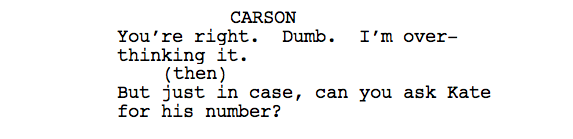

THE BEAT SHOULD NOT GO ON

There was a time and place for “beat” when the screenplay was a technical blueprint. But these days, it’s more about making the screenplay readable. Anything that breaks the suspension of disbelief is our enemy. So when you say “beat,” what does that mean? It means fake-ish artificial term that has no organic reason to be in your story. Whenever you can, replace “beat” with something more natural so as not to draw attention to its technical-ness. For example, I’d probably write this instead…

THE DREADED ‘WALL OF TEXT’

Okay, this above scene is kind of funny, but that’s not what we’re looking at. When a reader turns the page, they immediately see a general snapshot of said page. The last thing they want to see during this moment is a “WALL OF TEXT.” At least three paragraphs with five lines or more. At least one character who talks forever (or two characters who exchange 6-7 line chunks of dialogue each time they speak). There’s no doubt that there will be times in your script where you’ll need to write a lot. Characters do occasionally have monologues (even those should be rare though).

But if there are a lot of pages that look like this? With big huge paragraphs and character exchanges where both characters are taking forever to say shit? The reader has given up on you. The correct way to write is to rarely go over 3 lines per paragraph, and your characters shouldn’t exchange more than 2-3 lines at a time (this will differ depending on character and scene, but it’s an average to keep in mind). Also, it should be noted that the WORST place this can happen is on your first page. I see a LOT of amateur writers open with that wall of text and I just know the script is going to be bad. :(

IN SUMMARY

A good reader – and I’m talking about the reader who you’ll eventually have to get past to sell your script – takes his reading job just as seriously as you take your writing job. So he’s going to have his set of reading quirks, things he can’t stand. The last thing you want is to trigger any of those annoyances, because then the reader is judging you on something other than what they should be – the story. Like that wall of text. Again, when I see that, I know it’s over. I know it’s over right away. Sure, there are like 2 exceptions in the last 10 years of scripts overcoming this, but for the most part, readers know it’s a disaster. Just remember that your job is to make things as easy as humanly possible for the reader. You want their read to be effortless. So don’t do anything weird or annoying unless you’re absolutely sure it makes the reading experience and your story better.

What about you guys? What are some things that drive you nuts when you read?