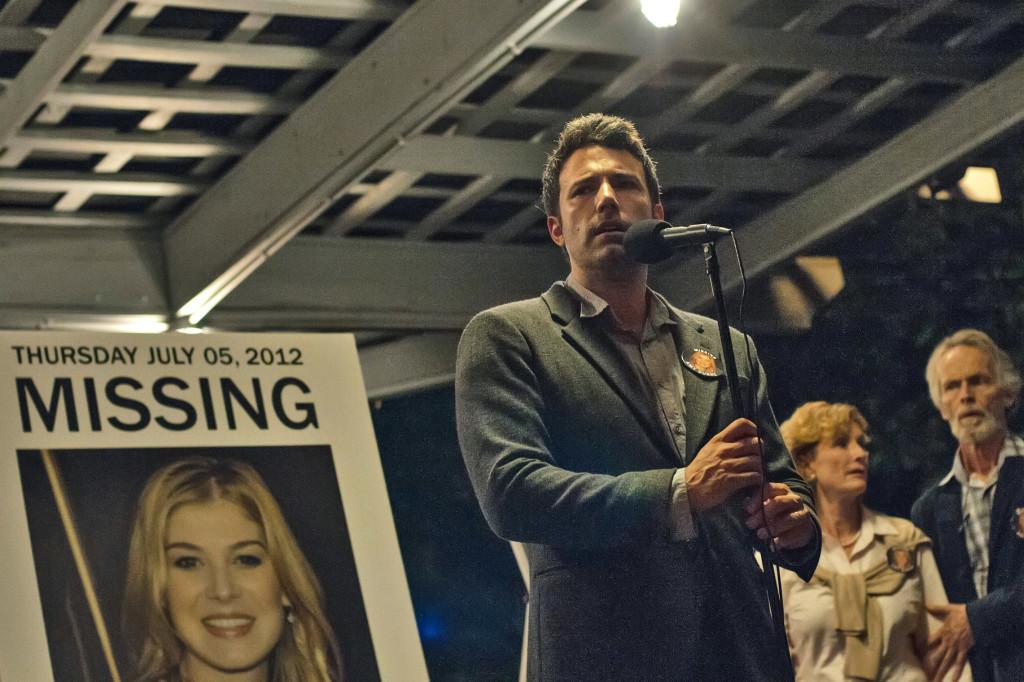

Gone Girl had a really exciting second act.

Gone Girl had a really exciting second act.

So the other day, a writer told me he’d been excited about entering the Scriptshadow 250, but lately, he didn’t know if he’d be able to finish his script on time. “You’ve got over three months,” I told him. “What don’t you have time to do?” “I just can’t seem to figure out second acts,” he confided. “I can make it through about 15 pages, but then I have no idea what to do next.”

Getting lost in the second act is not a new problem for screenwriters. In fact, on the list of screenwriting fears, it’s usually up there with writer’s block. But just like any problem in screenwriting, the solution presents itself once you break down the issue. And what I’ve found is that the writers who have problems with second acts are the same writers who never learned how to tell a story properly in the first place. So let’s start there.

Most stories are told by introducing a problem into a person’s life. That problem becomes the impetus for that person to ACT. This is obvious when you think about it. If you encounter a problem, you only have two options. Do something or do nothing. Most people will do something. That something becomes their GOAL. And the unresolved nature of that goal (will he or won’t he achieve it?) pulls the reader along until, at the end of the story, our person either succeeds or fails. So, to summarize:

THE GOAL IS ALWAYS TO SOLVE THE PROBLEM.

Look at almost any movie and this sentence holds true. (Problem) Hitler is looking for the most powerful religious artifact in history and plans to use it to take over the world. (Goal) Therefore, Indiana Jones must find that artifact first. (Problem) A giant monster has emerged from the bottom of the ocean and threatens to destroy the world. (Goal) The military must stop it. (Problem) In the popular film, Gone Girl, a wife has disappeared and the husband is suspected of her murder. (Goal) The husband must find out what happened to his wife.

Once you understand this basic principle, you have all the tools you need to tackle your second act. Because while a story starts out as a problem a character must solve, it becomes, in its second act, a series of conflicts that put our main character’s success in doubt. Let’s see if we can summarize that:

THE SECOND ACT IS WHERE YOUR MAIN CHARACTER ENCOUNTERS CONFLICT

This is a very simplistic assessment of the second act, but as you’ll see, it holds true in just about every movie you’ve ever seen. During those middle 60 minutes, nothing seems to be going right for the hero. He always appears to be running into trouble. This “plot conflict” is the first of two planes you need to master in the second act.

As we’ve already discussed, your character’s goal is to solve a problem. The second act, then, must make solving that problem the most difficult thing your character has ever had to do. You achieve this by placing OBSTACLES in front of the character’s goal.

For example, in Gone Girl, Nick needs to find out where Amy is so he doesn’t get sent to prison for the rest of his life. That’s his goal. The second act, then, is a series of obstacles thrown at Nick to make his job difficult. One of those obstacles is that his affair with another woman is exposed. If Nick is having an affair, it’s all the more reason for him to get rid of his wife. Later, another obstacle is introduced in the form of Amy’s journal. In the journal, Amy talks about how Nick is “dangerous,” how she’s scared of him, and how she thinks he might harm her. Yet another obstacle that makes his goal more difficult.

True, not any old obstacles will work. You need to be imaginative. And the obstacles themselves must hold weight. But if you continue to come up with good ones, it’s not hard to keep the reader’s interest.

But plot obstacles are only half of the second act battle. You also need to explore your hero’s relationships. When screenwriters give up on screenwriting, it’s usually right before they figure this part out. Because before you figure this tool out, your second acts are just plot. They’re robotic efficient story movers. But they lack emotion, lack soul, lack heart. In order to bring that feeling into the story, you need to master the art of inter-character conflict.

Inter-character conflict works like this. For every relationship between your main character and someone else, you need a SPECIFIC UNRESOLVED CONFLICT between them. Don’t be vague about this. Write it down somewhere. I’m going to make this very clear. Understanding the specific issue/problem/conflict in each of the key relationships in your screenplay allows you to explore your characters on an EMOTIONAL LEVEL so that your story isn’t just a robotic plot mover, but rather a living breathing exploration of the human condition. And that’s what makes a second act work. Here are a few unresolved conflicts between characters from well-known movies.

Silver Linings Playbook

Pat and Tiffany – She loves him, but he’s still in love with his ex-wife.

Frozen

Anna and Elsa – Elsa avoids a loving relationship with her sister in fear that she will hurt her.

Gone Girl

Nick and Detective Rhonda Boney – Despite wanting to believe him, she suspects that Nick killed his wife.

Neighbors

Mac and Teddy – Mac just wants to raise a family. Teddy just wants to have fun.

The Social Network

Mark and Eduardo – Mark is more interested in their company. Eduardo is more interested in their friendship.

Now I’m highlighting the main relationship in all of these movies, but your hero should have 2-5 key relationships in the script, and you should have a conflict for each of them. Once you have that conflict written down, every scene between those characters will, in some way, explore that issue. This is why we, as an audience, watch. We want to see if these characters are ever going to resolve their conflict!

When writers don’t inject problems/issues/conflicts into their relationships, the scenes between the characters are often lifeless. And why wouldn’t they be? If you don’t have anything to hash out, anything making your relationship difficult, it’s nearly impossible to draw drama out of the relationship.

Take a look at yesterday’s script, Huntsville. The key relationship in that story was 40 year old Hank and his friendship with 17 year old Josie. So I ask you – what’s the problem (or conflict) in this relationship? It’s pretty obvious, isn’t it? Hank wants Josie but can’t have her. It’s illegal. Therefore, every scene they’re in together is laced with that unresolved conflict. Will Hank make a move? Will the relationship go to the next level? The idea is to create a circumstance where the reader asks the question: “How is this going to be resolved?” If that question doesn’t come up, you’re not doing your job.

Take another recent script review: The Founder. What was the main problem between Ray Kroc and Mac McDonald? Ray wanted to expand the business. Mac was fine with the way the business was. Every phone call between the two in that second act revolved around this unresolved issue. These contentious discussions upped the conflict, which upped the entertainment value. The Founder doesn’t work if there isn’t any problem between Ray Kroc and Mac McDonald.

When seeking out conflicts to explore in relationships, two great places to look are your own life and (yup, I’m being totally serious here) reality TV. One of my friends has a testy relationship with her mom because her mom thinks she needs to get married now when she’s still young and pretty. My friend, however, isn’t in any rush. There isn’t a phone call that goes by between the two where this isn’t discussed outright, passive aggressively, or through subtext. Someone else I know disavowed his best friend because that friend is now dating his ex-girlfriend. You should see what happens when those two are in the same room. I once knew a guy who was in a three-year relationship with a woman he loved dearly, but that woman was an alcoholic and refused to quit drinking. Every day for him was a struggle.

Reality TV does this in a more on-the-nose way, but they’re still good at it. Most reality shows these days depend more on character than plot, so they put a ton of emphasis on relationship conflict, which is the same thing I’m asking you to do. It’s why you always find the religious nut and the gay marriage advocate on the same show. Or why two exes who never quite got over one another are brought back together. Or why a father is featured on the show of a man who’s never been able to achieve his dad’s approval. I’d argue that almost every reality TV show these days is about relationship resolution. So don’t be ashamed to study them.

That’s pretty much the basics for how to handle your second act. Plot obstacles and relationship conflict. And actually, when you think about it, it’s all conflict. Obstacles create conflict for the plot. Unresolved issues create conflict between characters. Are there other things to focus on in the second act? Of course (your main character battling his flaw for one). But if you master these two things, you should be able to write some kick-ass second acts. Which you’ll need to if you’re going to win the Scriptshadow 250! ☺