Hello everyone. First of all, I want to thank everybody who congratulated me on the New York Times article. I’m hosting a friend this week and therefore haven’t really had the time to process it all. It’s funny because I don’t read the New York Times. And you know how even if something is huge, if it’s not a part of your personal day to day life, you don’t hold it in the same high regard as everyone else? So, as crazy as it sounds, I didn’t think much of it. But then when all my New York friends and older friends and family (my older brethren have read the Times forever) found out, they were all like, “This is a really huge deal!” I was like, “It is?” So it’s hitting me a little harder this morning than it did over the weekend and now that it’s settling in, I’m very thankful for it. And once again, it wouldn’t have been possible without all of your support. So thank you to everyone who reads Scriptshadow, even the haters! This would not be possible without you.

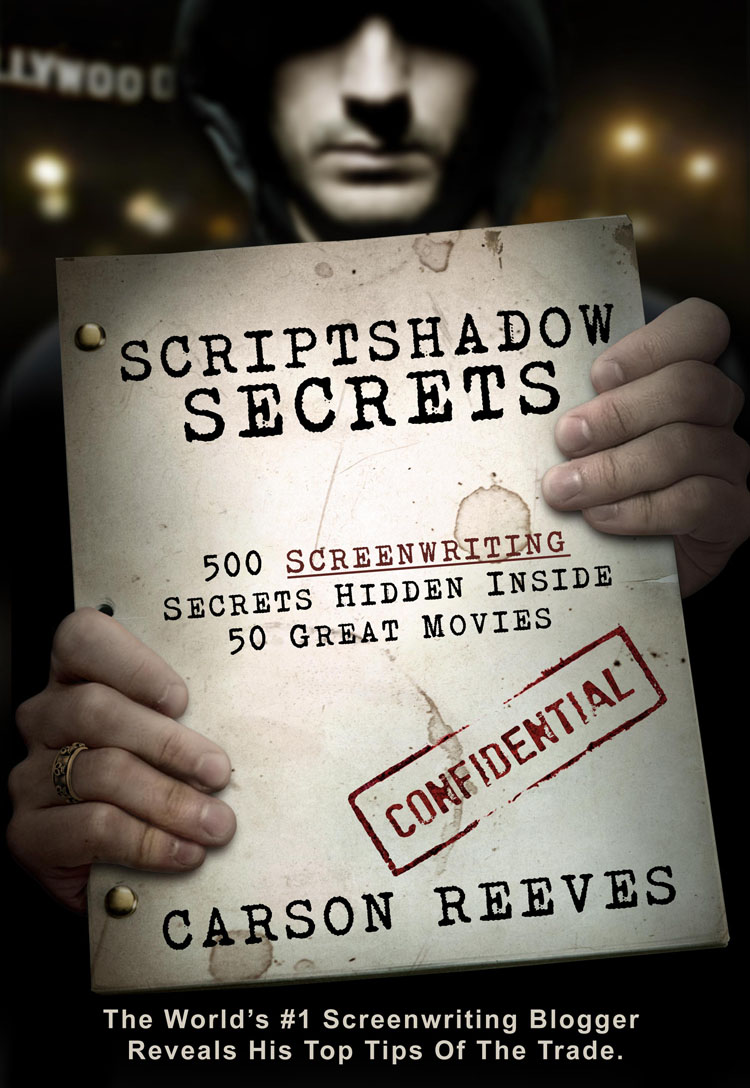

Now, this week is going to be a little different. Why? Because it’s SCRIPTSHADOW BOOK RELEASE WEEK!!! Some of you may have noticed that the book ad on the upper right-hand side has been changed from “Coming Soon” to “Buy now.” You can click that picture or click right here and you’ll be taken to Amazon where you can buy a copy of the e-book. Many of you have been asking me, “When can I get the book in physical form?” Unfortunately, paperback copies of the book won’t be available for another 1-2 months. We’ll get there. It’s just going to take some time.

So what’s the book about? Well, I basically took the most popular aspect of the site – the “What I learned” section – and applied that philosophy to an entire book. So I took movies like Raiders of The Lost Ark, The Social Network, and The 40 Year-Old Virgin (50 movies in all) and broke down 10 things I learned from each, which translates into 500 screenwriting lessons/tips/tools. I also wrote the book because that’s how I personally learn best, through example, so I always wished there had been a screenwriting book out there that taught solely through example. Well, now there is!

Now for those pounding your fists due to the fact that there will be no reviews this week, hold tight. This is Scriptshadow. I can’t go through an entire week without reviewing SOMETHING. So Wednesday is going to be realllly special. I’m reviewing 300 Years! This is a script I found from an unknown writer up in San Francisco named Peter Hirschmann, who’s not only super talented, but a really great guy. I loved the script so much, I asked to come on as producer, and we’re currently doing a rewrite before we go out to directors. In the spirit of Scriptshadow, I would LOVE to hear your feedback on it. There are a couple of places we feel it can be improved, so we’re open to ideas. If you want to read it, contact me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line “300 YEARS.”

And now, it’s time. The following is a small excerpt from the first chapter of my book, “Scriptshadow Secrets,” available in E-book format from Amazon. This opening section prepares you for the movie-tip section by introducing the basics of writing a screenplay. Tomorrow, we’ll delve into some actual tips. Enjoy! (p.s. Because I’m performing hosting duties all week, I’m not going to be as quick with moderation. So, sorry if your comment gets stuck. I will do my best to get them up as soon as possible).

Excerpt from Scriptshadow Secrets…

(edit: People have been asking if they need an ipad or Kindle to read the book. The answer is no. You just need to download the Kindle Reader to your PC and you can read it right from your computer. Download the Kindle App here).

STRUCTURE

Whenever you write a screenplay, you’re telling a story. A lot of writers forget this, and it’s funny because we tell stories every day. When you have a few beers with your buddies and share how you asked the intern out? You’re telling a story! When you replay the amazing three-run homer your son hit at T-ball? You’re telling a story! When you’re giving your professor an excuse for why you didn’t finish your homework? You’re telling a story! A screenplay is just another venue to tell a story.

In order to tell an entertaining story, though, one that’s going to keep your audience on the edge of their seats, you need to understand structure. Structure places the key moments of your story in the spots where they’ll create the most dramatic impact. Ignore structure, and your story will have no rhythm, no balance. It might be front-loaded or back-loaded, choppy or unfocused. For example, in the story about your son’s three-run homer, if you jump straight to the home run, your story will be short and anti-climactic. With good structure, you set the stage for that home run over time, leading to an exciting climax.

The structure you’ll be using for almost all of your scripts is the 3-Act Structure. Don’t be intimidated by its fancy moniker. All it means is that there are three phases to your story: a “Beginning,” a “Middle,” and an “End.” Or, if you want to take the training wheels off, a “Setup,” some “Conflict,” and a “Resolution.” If you’re going to write screenplays, then you’ll be writing 90-120 pages of story contained within this basic 3-Act format.

ACT 1 (20-30 pages long)

Act 1 sets up your hero and then throws a problem at him. That problem will propel him into the heart of the story. Let’s say our story is about a guy desperate to ask out a beautiful intern who works at his office. To start your story, you might show your hero staring longingly at the intern from afar. He may even text his buddy: “No more messing around. I’m asking her to the Christmas party this weekend!” Soon after, you’ll write what most screenwriters refer to as the “inciting incident,” which is a fancy way of saying, the “problem.” A great example of an inciting incident happens in the movie Shrek, when the fairy tale creatures move into Shrek’s swamp. This is the “problem” to which Shrek needs to find a solution. In our story, it might be when our office dude learns that it’s the intern’s last day at work! In other words, this is his last chance to ask her out!

This inevitably leads to our hero having to make a choice. Does he stick with his old life (never taking any chances) or man up and go for the goal (ask her out)? Well, we wouldn’t have a movie if the hero stayed put, so your character always goes after the goal. In Shrek, this moment occurs when Lord Farquand tells Shrek that if he rescues the princess, he can have his swamp back. In our office story, it might be as simple as Office Dude deciding he’s going to ask Gorgeous Intern out today. He knows she always makes copies at 11 o’clock. So he spiffs himself up and heads to the copier room.

ACT 2 (50-60 pages long)

A lot of people get confused by Act 2, so let me remind you of its nickname: “Conflict.” Act 2 is the act where all the resistance happens in your story. Your hero will encounter arguments, setbacks, physical battles, insecurities, broken relationships, obstacles, their past, the protective best friend, killers, guns, car chases, and 80-foot lizards – basically, anything that makes it harder for them to achieve their goal. The more things you throw at your character, the more conflict he’ll experience. And conflict is what makes your story fun to read!

In addition to this, every roadblock, every obstacle, every setback, should escalate in difficulty. Start small and keep building. In our office story, maybe our office character stops outside the copy room, takes a deep breath, checks his reflection in the window, practices the big question a couple of times, then opens the door. He finds Gorgeous Intern, but, lo and behold, she’s talking to Sammy the Office Stud, who has her doubled over with laughter. Oh snap! Obstacle encountered!

Pages 55-60 in your script are referred to as the “mid-point.” The mid-point is important because it’s where your story changes direction. Whatever the first half of your story was about, the mid-point will shift it in a slightly different direction. By doing this, you keep the story fresh. So in our office story, maybe the midpoint is the fire alarm going off, forcing everybody to evacuate the building. This will place the second half of your story in a new environment – outside. If you want to use a real movie example, the midpoint of The Godfather is when Michael kills the Captain and Sollozzo at the restaurant. There are a million different scenarios you can write for your mid-point, but something needs to happen to give the second-half of your screenplay a slightly different feel from the first-half. Otherwise, the reader will get borrrrrrr-ed.

The pages after the mid-point and before the third act, form what I call the “Screenwriting Bermuda Triangle.” It’s where most screenplays go to die. What often happens is that writers run out of ideas in the second act and start scribbling down a bunch of filler scenes until they can get to the climax. Filler scenes are script-killers and will destroy everything you’ve worked so hard for.

If you follow proper structure, however, you should be able to navigate the Bermuda Triangle. After the mid-point, keep upping the stakes of your story. Make the problems bigger and more difficult for your character. In our office story, maybe it’s freezing outside, so everyone is pissed-off when the fire alarm sounds. To make things worse, the gorgeous intern is now cuddling up with Sammy the Office Stud to stay warm. That’s when the boss hits us with a bombshell: if they can’t get back inside within the next 20 minutes, he’s calling it a day. Ahhhh! Our hero now has 20 minutes to ask Gorgeous Intern out or lose her forever!

As the pages tick away in this section, so too should the attainability of your character’s goal. The closer we get to the climax, the more dim your hero’s chances of achieving his goal should get. In our office story, perhaps a car splashes water over our hero’s suit, destroying his appearance. Or even worse, a rumor spreads that the company is downsizing next week and his job is on the chopping block. It looks like all hope is lost. This is often referred to as your hero’s lowest point and will signify the end of the second act. We might even see Sammy the Office Stud nudge Gorgeous Intern towards his car where they can “warm up,” as our hero watches on hopelessly .

ACT 3 (20-30 pages)

The final act of your screenplay is really about your hero’s inner transformation, which is complicated, so we’ll discuss it later in more detail. In short, after your hero reaches his “lowest point,” he’ll experience a rebirth, finally realizing the error of his ways. If he’s selfish, he’ll see the value of selflessness. If he’s fearful, he’ll find the strength to be brave. He won’t have completely transformed yet, but this realization will give him the confidence to go after the girl or take on the villain or look for the treasure one last time.

In our office story, our hero realizes that his whole life has been a series of missed opportunities because he’s been afraid to take chances. I call this the “epiphany moment” and it signifies that your hero is ready to take action. Our office hero straightens up, barges through the group, CHARGES after Gorgeous Intern, spins her around, and plants a big wet one on her. She, Sammy the Office Stud, and all the coworkers stare at our hero in shock. He can’t believe it either. He’s done it! He’s won over the girl of his dreams! That is, until – CRACK – a hand smacks him across the face. “Asshole!” the intern shouts, grabbing Sammy the Office Stud and stomping off. Our hero stands there, alone, and watches her leave. The End. Hey, I never said this story had a happy ending!

Now, it’s important to remember that this is the most basic way to tell a story: a beginning, a middle, and an end. But as you’ll see over the course of this book, movies have taken this basic template and mutated it into hundreds of different variations. For example, there are movies where the hero doesn’t have a goal. There are movies where the story’s told out of order. There are movies where there isn’t a traditional main character. These are all advanced techniques and before you attempt them, you need to know the basics. We’ve just reviewed the basics of structure. Now let’s take a look at the basics of storytelling.