Okay, first thing’s first. I am not a logline expert! There are probably people on these boards that know a lot more about loglines than I do (and therefore I welcome their criticisms). However, I am someone who’s received a few thousand loglines all designed to catch my attention and make me want to read your scripts. From that end, I can speak from experience, and my experience is that 90% of the loglines I read aren’t professional or well-constructed. Since your logline is your initial point of attack, the line that either gets you or doesn’t get you the all important read-request, it’s gotta be just as tight as your script. So, let’s take a look at what loglines are, and how you can improve them.

WHY A PROPERLY CONSTRUCTED LOGLINE IS SO IMPORTANT

People always used to say to me, “Make sure you write a proper logline!” stressing the word “proper” with an inordinate amount of vigor. I always dismissed them with a roll of the eyes and a, “I’ll write my logline however I want to, thank you very much.” Well, now that I’m on the other side, and I’ve read hundreds of loglines which I’ve then gone on to read the scripts for, I’ve realized that there’s a strong correlation between professional loglines and professional scripts. When a logline is really well constructed, the script is usually really well constructed. When a logline is confusing or unfocused, the script is usually confusing or unfocused. For that reason, when I see a logline that confuses me in even the slightest bit, I won’t read that script, as experience tells me that if they can’t make that one sentence comprehensible, there’s no way they’re making 110 pages comprehensible. Seasoned industry folks are looking for a clear concise summary of your story. For that reason, it’s essential that you get the logline right.

HOOK US

The single most important thing in a logline is the hook. There has to be some kind of intrigue, some kind of irony, some kind of high concept, some kind of unique subject matter, that grabs our interest. In other words, there has to be something in the logline that’s exciting. That word is, of course, subjective, but without a hook, you could construct the most technically perfect logline in the world and still no one will want to read it. It doesn’t matter if the scope’s big (Breaking into people’s minds to steal information) or small (A man is stuck in a coffin with no memory of how he got there), you gotta hook us. A teenager who has to save his mom and dad’s marriage is not a script I’d hurry to open. A teenager who gets stuck in the past and must figure out how to make his parents fall in love or else he’ll cease to exist? Now THAT’S a script I want to read.

WHAT IS A GOOD LOGLINE?

A good logline usually covers three bases. It gives us the main character, the main character’s goal, and the central conflict in the story (what’s preventing them from getting that goal). Let’s take a look at this in action. The logline for Black Swan might be: “A sheltered ballerina must train for the most important role of her career while fighting off fierce competition from her talented and dangerous understudy.” We have the main character (the ballerina), the goal (training for her role) and the central conflict (the other ballerina trying to steal the role from her). Bonus points if you can give or allude to the hero’s defining characteristic. This is usually done with an adjective. “A sheltered ballerina must train…” gives us a lot more information than “A ballerina must train.” And there it is. That’s your logline template.

KNOW THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN AN IDEA AND A LOGLINE

This is the biggest mistake amateurs make when constructing a logline. They think an idea, or a “concept” is a logline. So they might write, “A hockey player takes up golf and becomes a superstar that changes the sport.” (Happy Gilmore). That’s not a logline. That’s an idea. A logline fleshes out the details to give us a better understanding of the main character and the specific journey he goes on. So instead, that logline might look like this: “A hockey player with severe anger issues is forced to join the golf tour, a sport he detests, in order to save his Grandmother’s home.” Now instead of imagining a vague series of scenarios, we understand who our characters is (a hockey player), what he’s trying to do (save his grandmother’s house), and what’s standing in his way (a sport he hates).

IRONY IS A LOGLINE’S BEST FRIEND

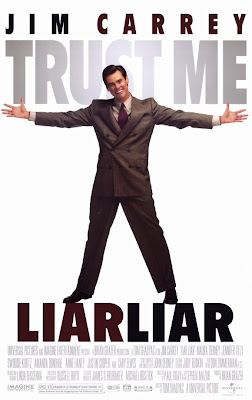

Okay, I’m not suggesting that every movie you write from this point on be based on an ironic premise, because there are plenty of great movies that aren’t, but I will tell you this. The loglines that read the best are the ones with some sort of irony in them, where the character and the situation are at odds with one another. A lawyer who can’t lie (Liar Liar). A king who can’t speak to his people (The King’s Speech). A Detroit cop investigating a case in Beverly Hills (Beverly Hills Cop). A time manager stuck on an island with all the time in the world (Cast Away). An alcoholic superhero (Hancock). These loglines will always catch a reader’s attention, so you’ll have a huge advantage if your concept contains irony.

EXAMPLES

Here are some good examples of well-written loglines I’ve found across the web. Notice in all of them how we have the main character, the goal, and the central source of conflict.

On the eve of World War 2, an adventurous archeology professor tries to find the mythical Ark Of The Covenant before the Germans, who plan on using the powerful relic to take over the world. (Raiders Of The Lost Ark)

In a future where criminals are arrested before the crime occurs, a drug addicted cop struggles on the lam to prove his innocence for a murder he has not yet committed. (Minority Report)

After a thirteen year old outcast accidentally destroys a mixtape belonging to her deceased parents, she struggles through an impossible journey to re-find each rare track in hopes of finally connecting with the parents she never knew. (Mixtape)

A precocious and selfish high school playwright whose life revolves around his unique private school, finds himself in a dangerous competition with its most famous and successful alumnus for the affection of a first grade teacher. (Rushmore)

A reclusive sociopath must fight his way across the wasteland of a dangerous postapocalyptic America to protect a sacred and mysterious book that holds the key to saving the future of humanity. (The Book Of Eli)

SOME EXAMPLES

Okay, now on to you guys. I’m going to finish this post up by listing 5 loglines I’ve recently received (for Amateur Friday) and explain why I haven’t picked them. The goal here is not to embarrass those who submitted, but rather put them inside the head of the person who’s using their loglines to determine whether to read their script. Hopefully they, as well as you guys, will learn something in the process. Enjoy.

THE WARRIOR POET – The Epic story of the early years of the Biblical figure David, who while fleeing from the paranoid and murderous King Saul becomes leader of a guerrilla unit of 600 soldiers and assassins in the harsh wilderness of Israel.

Jason’s a regular contributor on the site, and I know he’s been working on this script for awhile. Why then, did I not choose his logline? Good question. The subject matter itself sounds like it has potential, but there are some red flags that kept me away. The word “epic” itself is daunting. I think “epic” and I imagine 140/150 pages, which is an immediate “no way” since I read too many screenplays as it is and like to keep each read under the 1 hour and 45 minute mark if possible. The subject matter is weighty as well. It sounds like it’s going to be dense, with lots of long paragraphs, and will require copious amounts of concentration to stay involved. That sounds more like work than entertainment. And finally, the logline doesn’t indicate any character goal driving the story. Rather it implies a situation. After David flees, it sounds like he just hangs out in the Israeli forests with 600 soldiers for a few months. Where’s the point? Where’s the all-essential driving force? There isn’t one, which leaves me thinking that the story, as well, will not have a point or a driving force.

SMALL TOWN HITMAN – The world’s worst hitman is banished to Anytown, USA.

This logline is way too general. It doesn’t tell me enough about the story. I’ve seen a billion loglines about hitmen. What makes this one special? What makes me want to pick up THIS hitman screenplay over all the others? Again, scripts often reflect loglines. So if a logline is vague and generic, the script will likely be vague and generic. This logline needs some major fleshing out, more specificity, and more of a hook. “The world’s worst hitman is accidentally assigned to assassinate the number one criminal on the FBI’s most wanted list,” sounds like something with a lot more potential.

BLACKOUT – A band about to embark on their first world tour throws the party to end all parties, only to wake up with a corpse in their pool… Hilarity ensues.

There’s something too generic about this idea. Any dead body is a problem in a story, for sure. But there’s something too on the nose and obvious about a wild band having to deal with a dead body. A much more intriguing logline would consist of a CHRISTIAN ROCK BAND waking up and finding a dead body in their pool. Now you have irony. Now you have a movie. Also, I advise against using “Hilarity ensues” in any logline. I see it a lot, and since hilarity almost never ensues, it tends to send a subliminal message to the gatekeepers to “avoid this.”

THE PRIDE OF CLEVELAND – A WOMAN IN MID-LIFE CRISIS BECOMES AN ANARCHIST OUTLAW ON THE FBI’S “MOST WANTED” LIST WHEN SHE TRIES TO SAVE THE LIONS OF AFRICA FROM TOTAL EXTINCTION.

First of all, you definitely don’t want to present your logline in all caps. It’s too hard to read and comes off as unprofessional. My big problem here is that the story doesn’t make sense, at least as told through the logline. If someone heads off to Africa to save lions, why would the FBI care enough to put them on their most-wanted list? If she was going from continent to continent killing lions, trying to make lions extinct, I could see the FBI wanting to find her, but why would the FBI want to stop someone from saving lions? Isn’t that a good thing? And don’t they have more important criminals to take care of? Like child molesters and terrorists? It didn’t make sense to me. And if the logline doesn’t make sense, I’m not going to open the script.

THE DAY OF RECKONING – After a Zombie outbreak erupts, a devout Street Preacher must struggle to make it home and save his pregnant wife and young son while determined to keep to God’s commandments—especially, thou shalt not kill.

This is actually a well-constructed logline. Notice that we have our main character (our preacher). We’re told something about him (he’s “devout” and does his preaching on the “street”). We’re given his goal (make it home while protecting his wife and son), and we have a hook (he’s not allowed to kill any of the zombies along the way). This is something that I might pick up and read in the future. So why haven’t I yet? Simple. I have read a shitload of zombie scripts in the last 3 months. And while this sounds solid, it’s got nothing new or different enough in the well-tread zombie genre to make me want to pick it up right away.

And there you go. Hope this has helped. If you’d like, go ahead and post your own logline in the comments section and I (as well as the rest of the readers) will tell you if it needs work or not.