You got this one right, Scriptshadow Nation. What a script!

Genre: Historical Biography

Premise: The incredible true story behind one of America’s founding myths. After being kidnapped from his lands as a child, the Patuxet Indian Squanto spends his life fighting impossible odds to return home, setting in motion a series of events that changes the course of history.

About: The horse that led the race from start to finish, “The Savage.” Number 1 seed in The Scriptshadow Tournament, and now the champion!

Writer: Chris Ryan Yeazel

Details: 116 pages

Oh yeah.

Within a couple of pages I knew. I just knew why this won.

Within ten pages, The Savage had placed itself so far above the competition, I’m surprised any other scripts got votes against it.

More importantly, halfway through this script, I wasn’t even thinking about how it was the winner of the Scriptshadow Tournament. I was just lost in the story. I mean this is crazy! I’m not sure how true-to-history Chris’s adaptation was. But I never knew the story of Squanto. I know this though. Somebody needs to make this movie.

13 year old Native American, Squanto, a member of the Patuxet people, only wants one thing. To be a warrior. But when he’s stolen away by an Englishman sailing up the coast, every goal he’s ever known changes.

Squanto is whisked off to England, where he’s placed in the care of the eccentric governor, Ferdinando Gorges, a nobleman who funds the occasional trip to the Americas.

9 years later, and now fluent in English, Squanto hooks up with John Smith, he of Pocahontas fame. John is heading back to the Americas where he plans to establish a colony or two. He’s going to need a translator to deal with the natives, though. And Squanto looks like just the guy.

His payment for helping, Smith promises, will be to go back home. Thrilled, Squanto signs up. But Smith’s second in charge, Thomas Hunt, never trusts him. After taking care of business, Smith makes the mistake of allowing Hunt to escort Squanto home. And instead of delivering Squanto, Hunt kidnaps dozens of his people, takes them to Spain, and sells them off as slaves.

Forced to work the mines, Squanto eventually escapes with the help of some nearby monks. He becomes a monk himself, before finally heading back to England, where he gets a second shot to sail back home. It is there where he’s met with a truth so shocking, it will test him to his very core. Squanto will be forced to decide what life is worth, and if he can still contribute something good to a world that has only ever shown him cruelty.

The first thing I noticed about this script was the sophistication in the writing. Here’s a sample character description: “A gregarious, pompous ox of a man, Gorges does not speak so much as pontificate with operatic abandon.” That line doesn’t come from somebody who started screenwriting yesterday.

Something I commonly run into during reads is when the subject matter is above the writer’s current writing ability. They’re basically a 12 year old girl wearing mommy’s dress. No matter how hard they try, they don’t look like a grown woman.

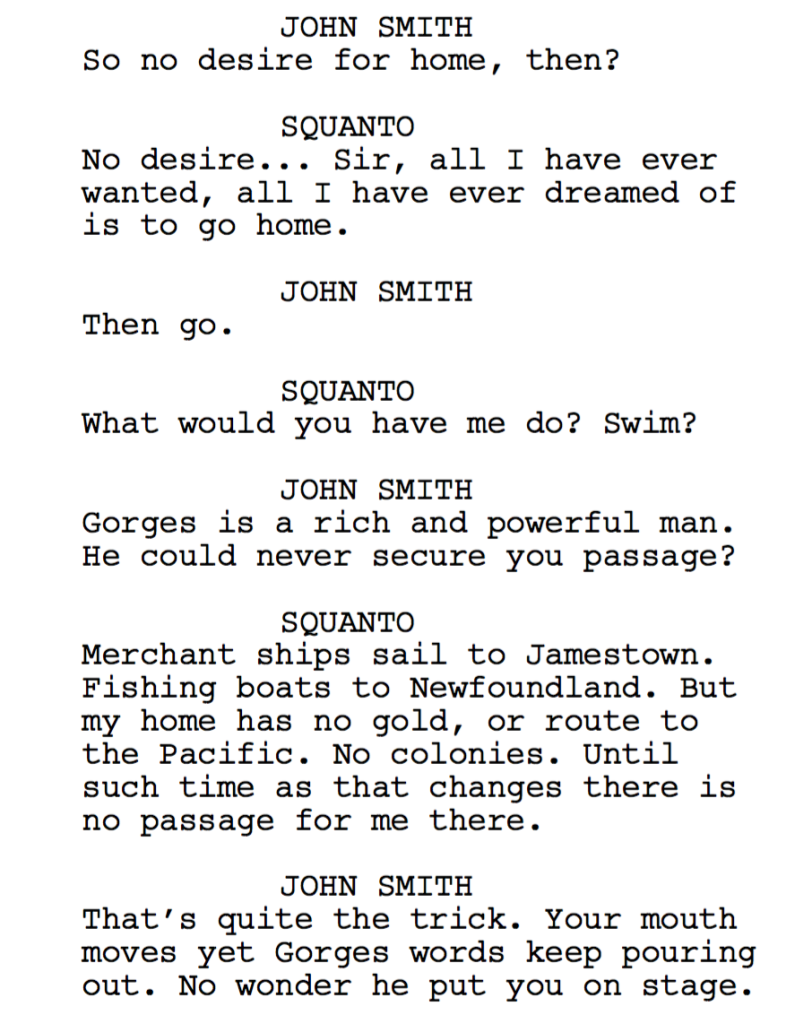

This was the opposite of that. Everything from the action to the dialogue was so strong, I wasn’t even thinking about it. It was just doing its job telling the story. I mean, here’s a sample dialogue exchange.

That last line alone is heads and tails above anything I read in this tournament. The easy line would’ve been something like: “You sound just like the man that owns you.” And believe me, I see that kind of line often. To rearrange the words into a clever insult, then tie that to a zinger paying off an earlier reference – that kind of thing doesn’t just happen. It demonstrates a writer who’s dedicated and on his game.

And there were a lot of clues here as to the high level of writing. For example, there’s an early slow scene where 12 year old Squanto is sharing a moment with the girl he loves, Hurit. It’s this beautiful little moment between them. Then, just as it’s coming to a close, we see warriors running through the forest. One. Then two more. Then two more. We realize a giant ship has arrived at sea and they’re all going to check it out.

The takeaway here is that Chris didn’t linger on this scene. He knows that readers are impatient. If you’re going to slow things down, you want to follow that up with something flashy. But not just that. You want to camoflauge the moment by using the end of the current scene to transition into the following scene. So we’re not just going from slow to fast. We’re doing it seamlessly.

Chris also exploits the use of dramatic undercurrents. An undercurrent is anything that’s occurring underneath the surface level of the story that creates a sense of interest, curiosity, or dread. It’s a trick to double or triple up the reader’s interest level.

An example would be Thomas Hunt, the evil second-in-command on John Smith’s voyage. Every moment that Squanto and Smith share, you see Hunt nearby, clenching his teeth. He hates this savage. And we know that he’s going to do something about it at some point. And that’s where the undercurrent is happening. Until this conflict is resolved, it’s in our heads, keeping us curious. Keeping us TURNING THE PAGES.

Here’s my only beef with the script, even though I understand why Chris did it. The script doesn’t build throughout its second half. There isn’t this big giant goal that Squanto has to take care of, like, say, the last gladiator event in Gladiator. Or the wife being taken in The Last of the Mohicans. Squanto is basically trying to stay alive. And while that’s compelling, it prevents the story from building up, which is how most people like their stories told.

For example, when Squanto finally gets back from the mines, he learns that Thomas Hunt was killed a long time ago in a random altercation at sea. It would’ve been so much better had Hunt gone back to the Americas and set up a colony where he was in charge, and when Squanto got back home, he learned of this colony, and went to enact revenge on him.

Or, a big chunk of the story goes to Massasoit, the leader of Squanto’s rival tribe. Massasoit captures a young Squanto in the opening after Squanto steals something from him. Massasoit is pissed, but he basically laughs it off and lets Squanto go.

Then, in the end, our ending revolves around Massasoit once more, as he doesn’t like that Sqaunto has become chummy with the new English neighbors. The reason why this sequence didn’t carry a lot of weight was because Massasoit was never that bad. He was nice enough to let Squanto go in the beginning.

If this man would’ve been responsible for the eradication of Squanto’s tribe, now we have the potential for a lights out ending. If this man would’ve been the embodiment of evil, now we have an impending showdown that we’re looking forward to.

But we don’t get anything like that, and it keep the last 30 pages from building.

With that said, after reading the final pages, I understood historically and thematically why Chris did what he did. However, I wonder if there’s a version of this out there that could have that bigger satisfying ending yet still keep the essence of what Chris was trying to do.

Either way, this was a hell of a read. I mean, what a life this man lived. It’s incredible. And thank God someone as talented as Chris was responsible for telling us his story. He really did it justice.

Script link: The Savage

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Going back to the Thomas Hunt undercurrent conversation… In general, anything that’s unresolved is something that is captivating your reader. That’s why you want multiple unresolved threads in your story at all times. You can get that through unresolved conflicts between characters. You can get it through multiple unresolved plot goals. There’s no limit on how many pieces of your story can be unresolved. So take advantage of that. A lot of beginner writers only see the final goal as their unresolved thread. So a newbie writer would’ve gone with: “Squanto tries to get home” and that’s it. But that’s not enough to keep our interest. You need to add extra unresolved storylines to keep us engaged. If you think about it, this is the essence of drama. If it’s resolved and cozy, there’s no reason for the reader to worry. And if we’re not worried about anything, we’re probably bored.