Is this the best sci-fi fantasy short story ever written?

Genre: Short Story – Drama/Fantasy

Premise: A young half-Chinese half-American boy struggles to connect with his Chinese mother, who doesn’t speak English.

About: This is a multiple award-winning short story by Ken Liu from his short story collection, “The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories.” You can find it on Amazon. I don’t think the short story can be found anywhere online, unfortunately.

Writer: Ken Liu

Details: Around 4000-5000 words

Ken Liu is really starting to blow up. The team that made 2018’s, “The Arrival,” is turning one of his short stories, “The Message,” about an alien archaeologist who studies extinct civilizations and reunites with a daughter he never knew he had, into a film. AMC is developing a series based on his short stories called Pantheon. You also have Game of Thrones creators David Benioff and D.B. Weiss, adapting Ken Liu’s English translation of the epic sci-fi novel, “The Three Body Problem,” (which won the 2015 Hugo Award for Best Novel, making it the first translated novel to have won the award) for Netflix.

When I started looking into Liu, I learned that his big blow-up moment came upon the release of the short story, The Paper Menagerie. That story achieved something that had never been done before, which is sweep the Hugo, Nebula and World Fantasy writing awards. Everybody says this short story is amazing.

Which has inspired a secondary question as I go into this review. If this is his best work, why isn’t anyone trying to adapt it? There might be an obvious answer to this by the time I finish (some stories just aren’t easy to adapt) or, if not, maybe this article will be the impetus for someone finally buying it.

With that in mind, let’s do this!

(by the way, this story is best enjoyed without knowing anything so I’d suggest reading it first if possible)

Jack is a young boy who lives in Connecticut with his American father and Chinese mother. Jack informs us right away that his father found his mom “in a catalog” for Chinese women looking for American husbands. Even at this young age, Jack considers this weird and something to be ashamed of.

Because his mother was a Chinese peasant, she doesn’t know any English. She tries. But the words never come out right and she becomes embarrassed. Because his father makes him, Jack learns Mandarin, but he resents that his mother isn’t trying harder to learn English, and therefore refuses to speak her native tongue.

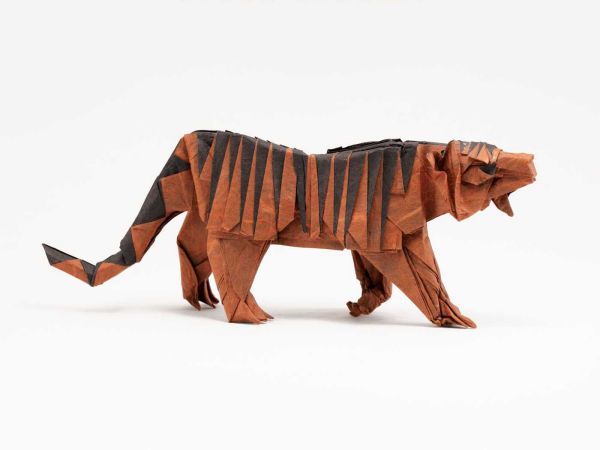

However, Jack’s mother finds another way to communicate with her son. One of the skills she learned from her village was creating special origami animals that are alive!

His family, being poor, couldn’t afford the fancy toys at the time (like all the Star Wars figures) so these origami animals became his toys. He would play with them for hours in his room, never tiring of them.

But when he became a teenager, his resentment for his mother skyrocketed. All this time and she still hadn’t properly learned English, meaning she couldn’t have a conversation with anyone, even her own son. Jack began talking to his mom less and less and even boxed away all her origami animals and threw them in the attic.

During his college application process, his mom gets sick. Her insistence to not be a bother to anyone had meant, by the time she checked in with a doctor, her cancer had spread too far to be treated. Even at this moment, Jack could not muster up any emotion for his mother. Here he was about to pick a college and his mom was still finding a way to mess it up. When he goes out to school in California, his mother dies.

Years later, Jack’s girlfriend finds his old box of origami animals and after she leaves for the day they, once again, come alive. Jack plays with them and it’s just like he was a kid again. Then he spots something on his favorite animal. As he unfolds it, he realize his mother has written a note inside. But it’s in Chinese. So Jack goes to someone who can translate it for him, and the woman reads his mother’s letter to Jack, which tells him the full story of her devastating childhood and how her life was meaningless until he showed up in it.

Okay.

I challenge anyone to read this story and not start bawling from the get-go. This is the saddest story ever. But good sad. “Gets to the heart of broken mother-son relationship” good sad.

I read a lot of screenplays that try to make you cry. Rarely do they achieve it. People think all you need to do to make a reader cry is give someone cancer. Have them die before ever saying “I love you” and people will eat it up. Making people cry is surprisingly difficult. There’s something about the act of trying to make someone cry that keeps them from crying. It’s almost like they know what you’re up to. For emotion to hit on that level, it has to feel like real life. Not like a writer trying to manipulate your emotions.

But one thread that seems to be present in a lot of cry movies is an unresolved family relationship. It could be a man and his wife, a father and daughter, a sister and brother, or, in this case, a mother and son.

I’m not going to pretend like I know the exact code for why this worked because I think nailing an emotionally brilliant story is always going to be a “lightning in a bottle” scenario. But I found it interesting that Liu reversed the typical roles in this kind of story. Instead of the parent being the one who disassociates from the child, it’s the child who pulls away from the parent. And for, whatever reason, that’s more heartbreaking. A child isn’t supposed to despise his mother.

That’s also a big reason why we’re turning the pages. Whenever you set up an unresolved scenario between two characters, we’re naturally going to want that relationship to be mended. It’s painful to walk away from something this emotionally powerful without knowing how it ends. Just by setting this scenario up, you’ve ensured that we’re going to read the full story.

But where Paper Menagerie separates itself from the 10 million other stories that have also tried and failed to make you weep, is this “strange attractor” in the origami animals. The story isn’t just mom and son arguing every day, which is the typical scenario I encounter in similar setups. The mom speaks to Jack through the animals. They become the only way the two communicate. And that adds a special element that elevates the story.

Another small detail was the meanness of Jack. Now, normally, you don’t want your main character to be mean. Once you cross a certain threshold of un-likability for your protagonist, the reader dislikes them and no longer cares about their journey.

What this does is it scares writers into always writing nice protagonists. The problem with that is that there’s nobody on the planet who’s perfect. We’re all flawed. We all have unpopular opinions. Mean thoughts. And if you take that arena away from your hero, you also take away their truth. You are now constructing something that doesn’t exist. And readers pick up on that.

The reason why it works here is because WE UNDERSTAND WHY JACK FEELS THIS WAY. That’s the key to making “mean” protagonists work. As long as we understand where their anger or meanness comes from, or, even better, we can relate to it in some way, then the meanness is going to work.

Jack is lonely. He is half-Chinese in a town where there are no other Chinese kids. Everyone knows his mom was purchased. When friends come over, his mom never speaks because she doesn’t know English. As a kid, this is embarrassing. Cause you have to deal with the effects of that every day. Of course you’re going to have resentment towards your mother. Once you’ve grounded the central story emotions in that reality, you’re golden. Because now we believe what we’re reading to be true and our focus shifts to, “Will this broken bridge ever be mended?”

Finally, I want to talk about the big final letter. The “final letter” scenario is actually something I see quite a bit in screenplays. Everyone thinks they’re being original when they do it but, trust me, it’s not original. And most of these writers fail gloriously with these letters. The reason being that they write something too obvious. “I always loved you. I think you’re going to become an amazing person. I wish we could’ve been closer but I’ve learned with time we will always be together spiritually… blah blah blah.”

This letter hit on some of those things, but it wrapped them around two key choices that elevated the letter beyond your typical “end of movie letter moment.” The first was she told the story of her childhood. Again, most writers are thinking literally: “I need to have mother tell son how she feels.” That’s obvious and rarely works. So to instead talk about her childhood shifts the focus away from her feelings about him and tells us about her. It was unexpected and her background was so detailed and interesting that it was almost like a story in itself we wanted to know the ending to.

The second thing Liu does (spoiler) is that the letter doesn’t end on a happy note. It isn’t one of those, “Go out there and seize the day!” endings. It’s more of a, “I was devastated we could never communicate and I always wished you gave me more of a chance” endings. That simple shift takes this from a perfect wrapped–in-a-bow Hollywood ending to something more realistic, more true to life.

I see now why everyone went nuts for this. It’s almost a perfect story. I don’t think they can turn it into a movie though. It works because its short form allows it to stay hyper-focused on the relevant variables (the mom, the origami animals). Once you extrapolate that and add a bunch of other plot, the concept becomes distilled and the animals don’t make as much sense.

I don’t know. Maybe someone would be able to figure it out. I’m surprised no one’s tried. Like I said earlier, maybe they will now.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[x] genius

What I learned: Ken Liu has an interesting philosophy in how he treats his first draft. He calls it the “Negative First Draft.” Here is his explanation to tor.com. – I usually start with what I call the negative-first draft. This is the draft where I’m just getting the story down on the page. There are continuity errors, the emotional conflict is a mess, characters are inconsistent, etc. etc. I don’t care. I just need to get the mess in my head down on the page and figure it out.The editing pass to go from the negative-first draft to the zeroth draft is where I focus on the emotional core of the story. I try to figure out what is the core of the story, and pare away all that’s irrelevant. I still don’t care much about the plot and other issues at this stage.

The pass to go from zeroth to first draft is where the “magic” happens — this is where the plot is sorted out, characters are defined, thematic echoes and parallels sharpened, etc. etc. This is basically my favorite stage because now that the emotional core is in place, I can focus on building the narrative machine around it.