I was chatting with a screenwriter who’s fairly new to the medium. He’d written a Breaking Bad type pilot that was good. However, it had the potential to be a lot better if he improved his scene-writing. There were too many scenes in the pilot that were treading water. Conversations that didn’t have enough bite to them. Character introductions that didn’t do much beyond introduce the character. Scenes that set up relevant information but not in an exciting way.

As we talked about this, I became sympathetic to his plight in that I remember going through the same thing myself. And I think all writers do. We initially believe that a scene is a cozy placemat for relevant story information. It’s a means to an end – a way to convey a thought, introduce a character, make a few jokes, establish a relationship, expose relevant plot points. A scene, in those early stages of writing, is treated casually. I mean, there are so many of them, right?

It’s only later on in the journey when you realize how quickly a reader can become bored (3 boring scenes in a row and you’re done) that you begin valuing individual scenes. Scenes should be treated like self-contained pieces of entertainment that drudge up some kind of reaction from the reader. And you achieve this in one of two ways. By injecting conflict. Or by creating a scenario.

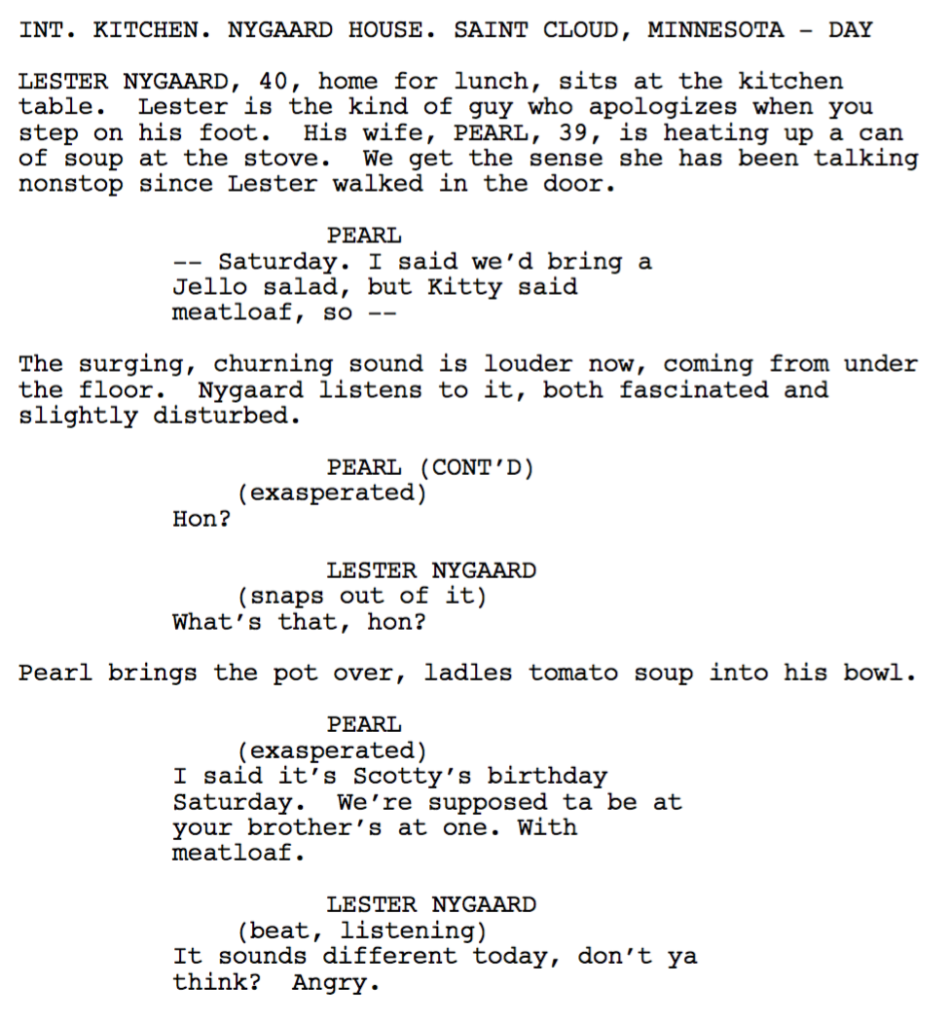

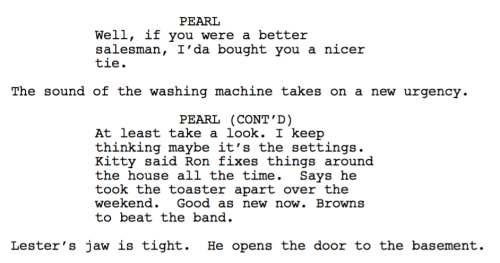

The above scene is taken from the Season 1 pilot pf Fargo. This is the perfect example of a scene dictated by conflict. And it’s not over-the-top obvious conflict, which I think is how most screenwriters view conflict. The conflict is understated. It plays underneath the surface in a passive-aggressive manner. Regardless of how the conflict is presented, the important thing is that IT IS PRESENTED.

A new writer may have believed they had to introduce these characters in a normal light and get the reader used to them before writing a scene like this. But veteran writers know that you don’t have time for that. The clock starts ticking the second the reader starts reading. I’ve never met a reader who’s said, “I give the writer a few scenes to warm up before I start evaluating them.” No. The evaluation starts immediately.

And this scene is just perfect in its conflict-execution. The longer the scene goes on, the more Pearl is digging into Lester, passive-aggressively using his successful brother to get him to work harder. This is exactly how you use conflict to write a great scene.

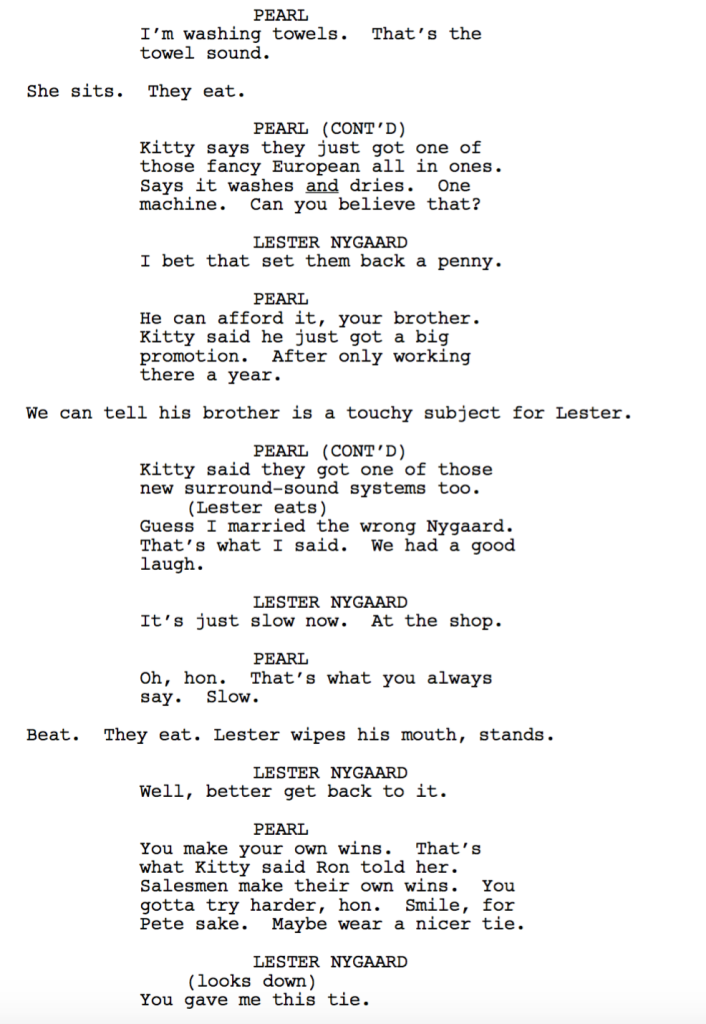

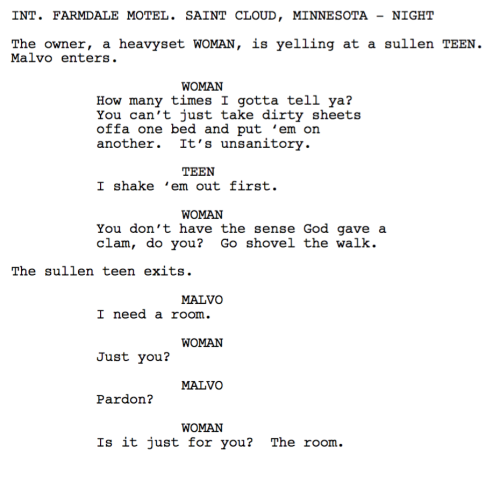

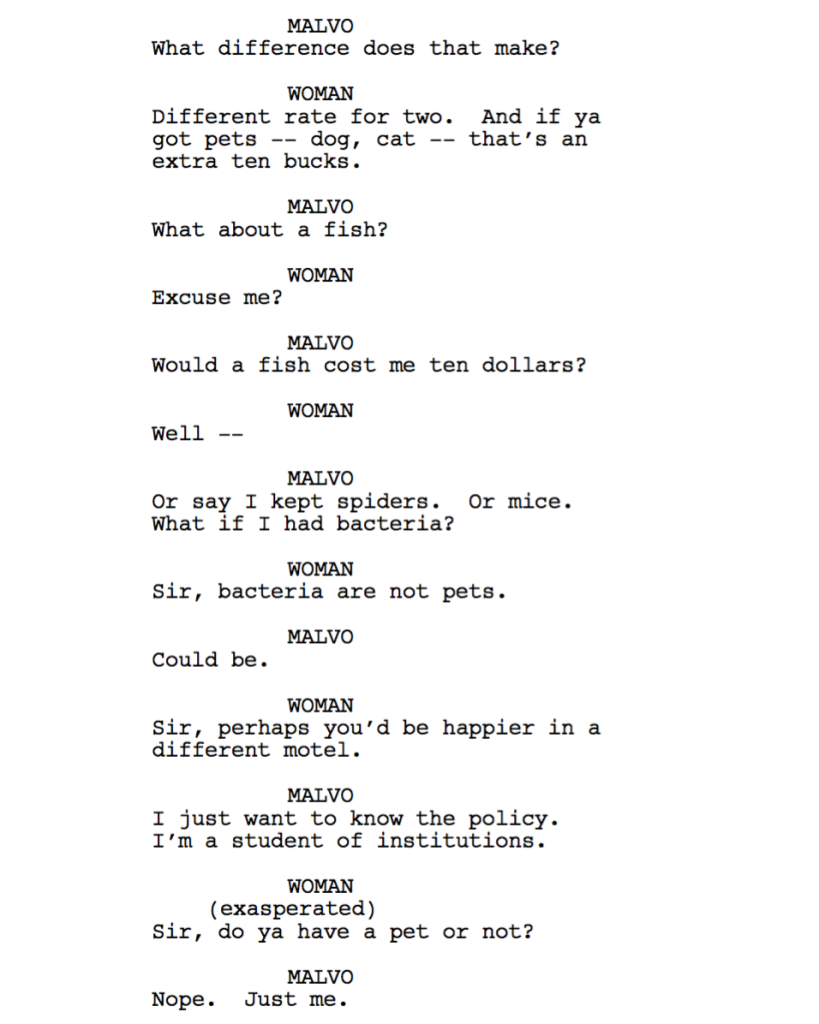

Another great use of conflict comes later in the pilot when Malvo (the villain in the series), goes to get a hotel room. I want you to pay attention to this scene because 99% of new writers would write this in a basic straightforward “I’d like a room please” way. Note how Hawley adds a nice dose of conflict to the scene instead…

The other option you have when writing scenes is turning them into SCENARIOS. In a scenario, you are building a problem into a scene that needs to be resolved. While conflict scenes don’t require much structure, scenarios are like mini-movies. You have a beginning (introduce a problem), a middle (try to resolve it as obstacles arise), and an end (they either succeed or fail). A scenario could be the hero finds a dead body. The hero’s picked on by a bully. The landlord wants their money. You need to find a team of superheroes (Deadpool 2). A husband tells his wife he wants a divorce. Someone’s been bit by a zombie and they need you to kill them (Zombieland). You’re about to get married and the ex shows up. Your boyfriend left you alone in a house with his two creepy friends, who look like they’re up to no good (Revenge).

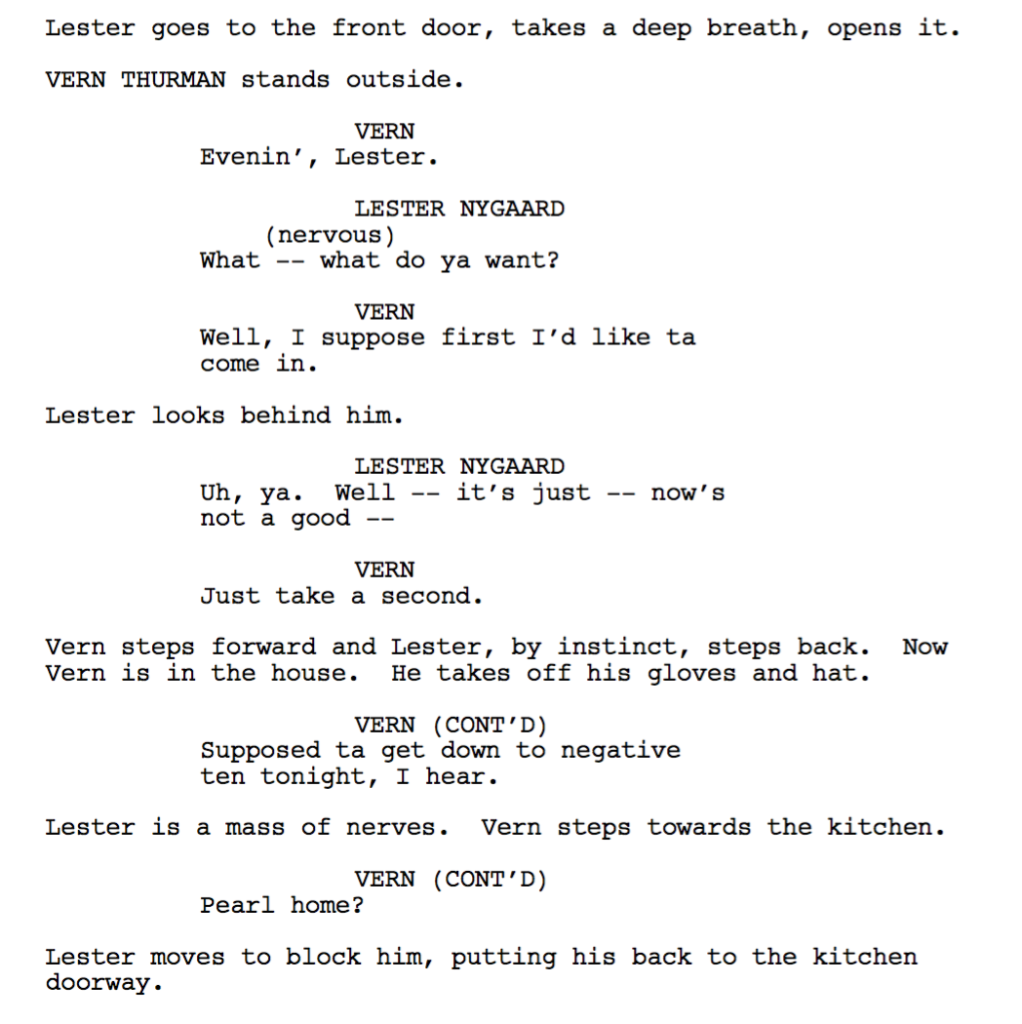

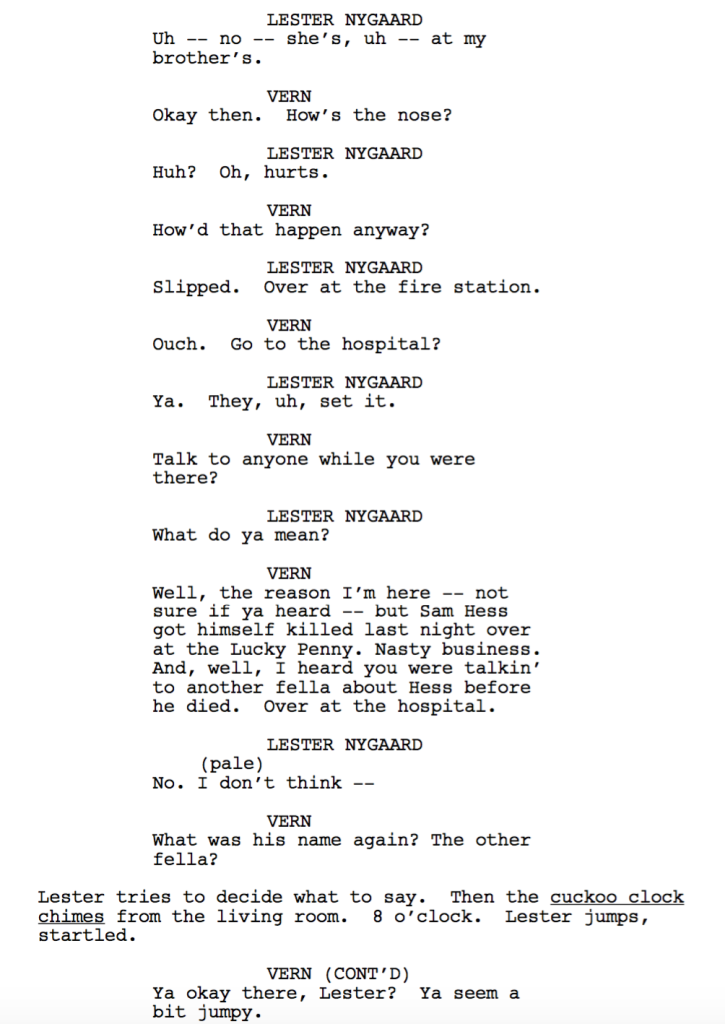

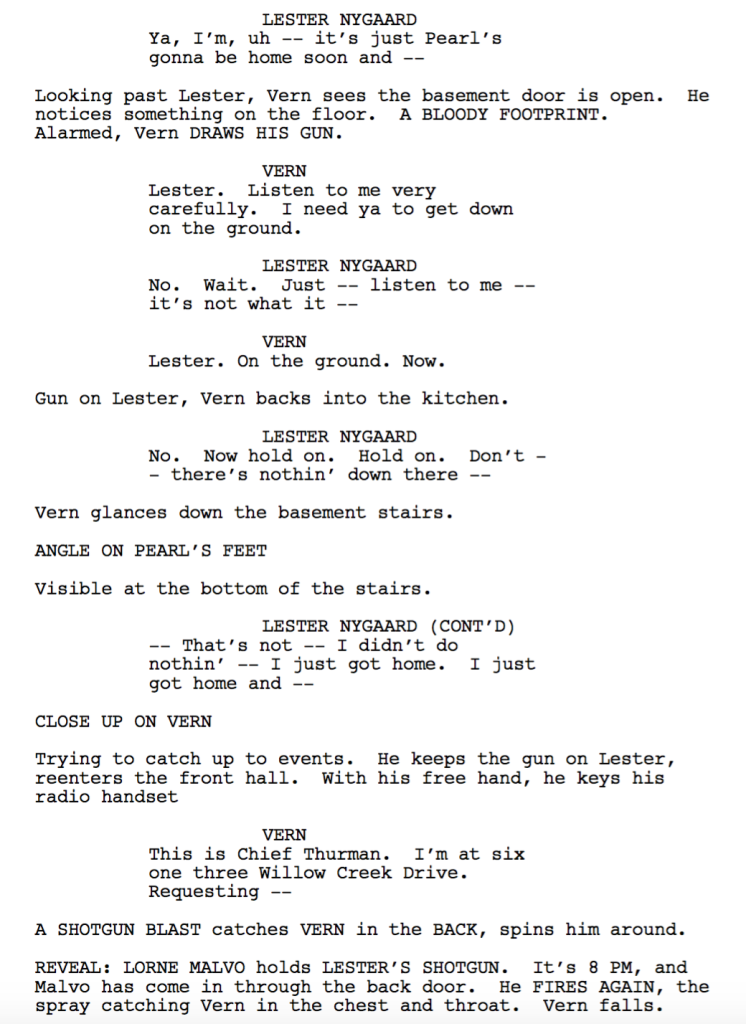

Here’s a good example of a SCENARIO in the Fargo pilot. It takes place later, after Lester kills his wife. Lester’s waiting for Malvo to come over to help him. However, police officer Vern unexpectedly shows up because he thinks Lester may be connected to an earlier murder in the story.

Any scene that isn’t dictated by conflict or a scenario should make you squirm. It should make you feel uneasy inside when writing it. Sometimes you have to write them. But they should only be used in specific circumstances. For example, if you just had a super-long intense scene, like the birth scene in A Quiet Place, you’ve earned a scene where the characters can just sit and talk. Err, well, maybe sit and sign language for that movie. But you get what I mean. Also, keep these scenes short. Any scene that’s absent of conflict or a scenario isn’t entertaining. So move through it quickly. And scenes with big reveals are exempt as well. For example, if John finally figures out who murdered his mother, you don’t need to worry about conflict or scenarios in that scene. The excitement of the reveal alone will carry the moment.

Other than that, use common sense. You’re trying to make every scene entertaining. These are the two most effective ways of doing so. If you’re not using them, you better have a darn good reason why. Good luck and go write some kick-ass scenes!