I’m not going to lie. I’m fascinated by Jordan Peele’s “Nope.”

Now that I’ve had some time to reflect on the film, I better appreciate what Peele has done. He swung for the fences in an industry that locks you in a batting cage. There’s something big and crazy and mystical about this movie that makes it unlike any other movie experience this year. And that’s to be admired.

But “Nope” is also a shining example of what an unfinished spec script looks like when it’s up on screen. It’s uneven. It’s sloppy. The main character isn’t very likable. The climax lacks clarity. You can feel the story trying to find itself as the movie is happening.

Who the f@%& is this character???

Who the f@%& is this character???

Which is what I want to talk about today. A finished script should never read like the writer is still playing with ideas, still trying to figure things out. Your script should have a certainty behind it. It should feel solid, like it always knows where it’s going.

To understand why this happens, you must first understand that a screenplay is a living breathing thing. We think we know our story when we start writing it. But, often times, we’ll discover new things that weren’t in the original plan. And, as an artist, it’s our duty to explore those new avenues to see if there’s anything there.

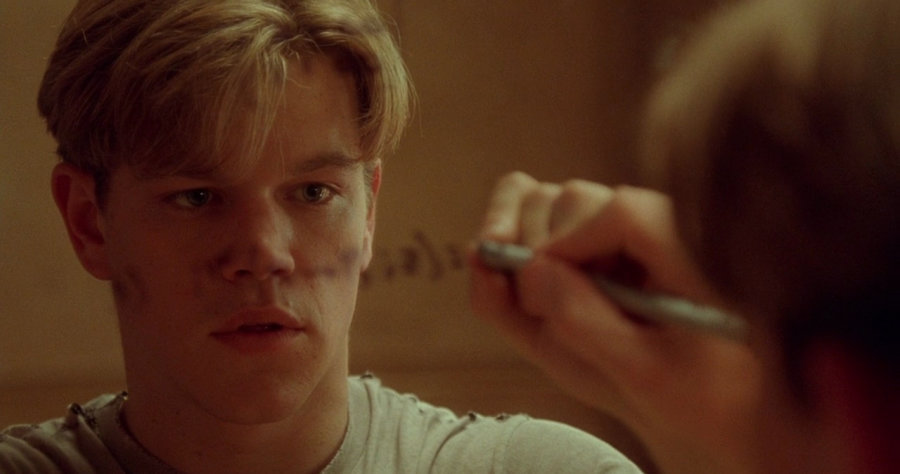

The most famous example of this is Good Will Hunting.

That movie started off as a thriller chronicling a genius mathematician who’s being pursued by the government for his abilities. But the drafts that Matt Damon and Ben Affleck were writing showed much more promise in the story’s character development, particularly the relationship between Will and his psychiatrist.

Matt and Ben did not want to change their story. But they were unknown back then and, in order to get the movie made, had to do what Castle Rock, who owned the rights, wanted them to do. So they scrapped the thriller angle and made it a character piece. The rest is history.

Part of what drafts 2, 3, 4, and 5 are about is identifying what’s working in your script and what’s not working, then leaning into the stuff that’s working. Just like Matt and Ben didn’t expect Psychiatrist Sean to be as interesting a character as he was, you might come up with a character, in the heat of writing, who you never thought of before you started, and that character might turn out to be a game-changer.

It’s in your best interest to then rethink your story to better incorporate that character. If that changes your movie – heck, even if it changes your genre – you have to consider it. That doesn’t mean you *have to* to deviate from your original vision every time this happens. But you should certainly weigh the pros and cons of the new option before writing it off.

I can’t help but think of this when reflecting on “Nope.”

Jordan Peele clearly had this vision of two Hollywood horse ranchers who discover that a UFO might be killing their horses. Admittedly, when you get that original idea in your head, it’s very hard to move away from it. So I suspect that once he had that idea, he never considered deviating. Which is too bad. Because it prevented him from writing a much better movie.

I don’t know how Peele conceived of the Ricky subplot. But based on his interviews and how obsessed he was with this monkey-massacre sitcom backstory, I assume it went something like this.

Peele had his crazy horse rancher UFO story over on one side. But he’d read about that story years ago (which we all did) about a monkey that tore its female owner’s face off. And he was so haunted by it that he just HAD to get it into his movie somehow. But how?

It would be too weird if the monkey massacre happened in the present. It would detract from the UFO-horse stuff. So he knew he had to put it in the past. Okay, well, how do we tie some crazed monkey backstory to the present? Maybe we have the woman whose face the monkey ripped off, many years later, involved in the story somehow.

They have animals in movies and TV shows all the time. What if this monkey was on a sitcom? And he didn’t just tear one person’s face off, he went ballistic and started attacking everyone on set? Okay, that’s cool. What if there’s a kid on this sitcom and he somehow comes away unscathed? And what if, many years later, he has his own little Western theme park out in the boondocks, not far from our horse ranchers? Okay, now we’re gradually finding tentacles to connect these two storylines.

Unfortunately, that’s as far as Jordan Peele went. Ricky (the kid from the sitcom) was going to be a supporting character in the movie.

This is the critical moment as an artist where you need to step back and objectively ask the question: Which of my two storylines is more interesting? The former kid sitcom star who survived a horrific monkey attack that killed two of his cast members and ripped the face off another, who’s put together a theme park where he tries to lure in UFOs… or a couple of horse ranchers who occasionally rent their horses to Hollywood?

Is it even a competition?

One’s a 9 out of 10 on the interesting scale.

The other is a 4 out of 10 at best.

Not only that but you could easily slide many of the current story elements over to the Ricky plot. For example, Ricky needs horses too. So if you really wanted to do the horse thing, you still have your horses as a main part of the plot. You could’ve even kept OJ. Have OJ begrudgingly working for Ricky. When the sh#t hits the fan, Ricky and OJ have to team up, which, unlike what they currently have, would’ve been fun to watch, since OJ doesn’t like Ricky.

Now some of you may be saying, “Hold on, Carson. Let’s play this out with some other movies. What about Star Wars? Han Solo had a way more interesting life than Luke Skywalker. Are you saying that George Lucas should’ve scrapped the whole Luke Skywalker Obi-Wan journey and made Star Wars, “The Adventures of Han Solo” instead? Cause we later saw the Han Solo movie. And it sucked.”

Totally fair argument. But I would combat that by saying while, yes, Han was the cooler character, Luke and Obi-Wan had the way better story. And since Han becomes a big part of the team after they meet anyway, we get all the Han Solo we can handle.

Here, Ricky has the better storyline AND is the more interesting character. He has the better story because he has an actual theme park he’s running. He’s putting all his resources into this new show. He doesn’t know if it’s going to work or not. If it doesn’t, it might bankrupt his whole business. Just as I’m writing this out, I’m imagining a 20 times better movie.

Ricky is also a guy who went through the most traumatic experience a kid could possibly go through. Yet here he is today, chipper and upbeat, always in a good mood. He clearly hasn’t dealt with that trauma. If we had more time with him, we’d be able to build more of an arc into that disconnect and see what happens when he finally breaks down and accepts what he saw.

So why did we build the story around the ranchers again?

One of two reasons, likely. As I said, once Peele locked into this idea of ranchers, he couldn’t let it go. He just had to tell the story from their point of view because they’re who he originally envisioned going through this. Another possibility is that he simply ran out of time. Unlike his 10 year journey writing Get Out, I’m guessing Universal dictated the release date of this film, which was strict enough that it prevented Peele from writing as many drafts as he would’ve wanted.

Which sucks because, he might’ve eventually figured this out. It’s clear to everyone who watched the movie that he was way more into Ricky’s storyline than the ranchers. That whole world of Ricky’s was like a sandbox full of toys. Every direction you looked (his current rodeo show, his old sitcom, killer monkeys, a weird theme park, maimed co-workers from his past) there was something to play with. Yet we instead get scenes like being stuck in Angel’s apartment while our three loser protagonists smoke weed together. It’s like, “uhhhh, I think there’s a better movie over this way, guys?”

Use this as a cautionary tale. Our minds are wonderful creative instruments and, sometimes, they come up with inspiration in the most unexpected of places. It could be that you’re writing a zombie movie and conceive one of your characters as an amazingly weird and captivating chess player. If Chess Guy is, far and away, the best thing about your zombie script, maybe you shouldn’t be writing a zombie script anymore.

Believe me, I know these choices aren’t easy. The more time you’ve invested in a storyline, the less motivation you have to change it. And, of course, there’s the danger of changing your mind *too much*. If you keep changing your script’s direction every time you come up with a new idea, you’re never going to finish. But if you encounter a scenario like Jordan Peele’s, “Nope,” where the subplot is actually way cooler than the main plot, you have to at least entertain the change. Cause I believe Jordan Peele missing the cue that Ricky was the main plot for Nope was the difference between making an okay movie and a great one.

Are you looking for help on your latest screenplay? – Let someone who’s read over 10,000 scripts identify your screenplay’s weak points and how to fix them. I have a 4 page notes package (2300-2500 words) or the more detailed 8 page option (4600-5000 words). I also give feedback on loglines, outlines, synopses, first acts, or any aspect of screenwriting you need help with. This includes Zoom calls discussing anything from talking through your script to getting advice on how to break into the industry. If you’re interested, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and let’s set something up! I look forward to working with you.