Sports movies are some of the hardest movies to make work because they’re so inherently cliched. You got some sports person, either an athlete or a coach or a GM, who’s an underdog in some sense, and then they fight to get to the top where they finally win the big game and HOORAY, we’re all happy.

In theory.

But in reality, whenever you see a sports movie on the docket, you feel like you’ve already seen it before. That was my issue with Hustle. I watched the trailer and I thought, “Okay, I definitely don’t have to see that movie.” Because it looked exactly like every other sports movie.

But I noticed a few of you talking about it in the comments and I thought, okay, I’ll give it a chance, fully expecting to tap out within 15 minutes.

But 15 minutes turned into 30, 30 to 60, and 60 until I reached the credits. The movie kept my attention the whole way through.

This made me stop, as it always does, and evaluate what happened to make me become so invested in this story. Cause I’m bored by most movies. Screenplays only have a handful of directions they can go. So it’s not hard to predict where they’re going.

“Hustle” was no exception. It went down the route I mostly knew it would go down. Yet I rooted for the characters. Yet I cared. Yet I was wondering how things would get resolved.

I can’t emphasize, enough, how important it is to answer this question. Because we are all working with a template that has been used, re-used, chewed up, spit out, regurgitated, reborn, used again, and used some more with every one of our screenplays. We are always fighting the battle of telling a story that’s already been told.

So if you can understand how a small percentage of these stories end up being good, you don’t have to reinvent the wheel every time you come up with a concept. You know that you can take a generic template and make it exciting.

Which is what Hustle did.

But how did it do it?

The answer is obvious yet complicated. What you first must accept is that there isn’t anything you can do plot wise that audiences haven’t seen before. Once every few years, somebody comes up with some whopper of a plot twist (Bruce Willis is a ghost!) that we didn’t see coming. But it’s hard to come up with truly shocking plot developments consistently.

I caught The Man From Toronto this weekend, which was a reasonably fun movie. But that movie literally hits every single Screenwriting 101 story beat that the screenwriting teachers say you have to hit. As a result, I will not remember any of it by the end of the month.

Luckily, there’s a way to overcome this issue.

You do it with your characters.

And the nice thing about this solution, is you really only have to do it with your hero.

If you can make us root for your hero, we will like your screenplay regardless of what you do with the plot. I know that sounds like a controversial statement but it really isn’t. It’s no different than if you meet a new friend or girlfriend or boyfriend who you really like. Do you need to travel to New York and take trips to the top of the Empire State Building to be happy around that person? No. You could literally lay on the couch for 10 straight hours eating Oreos and that would be enough.

Same deal here. Audiences are less concerned with experiencing some amazing plot when they love the main character. For them, just being around him and seeing what he’s going to do next is enough.

Now does that mean you shouldn’t try to write the best plot possible? Of course not. You want to enhance the experience of hanging out with that character as much as possible. But what it does mean is that you don’t have to worry as much that the predictability of your plot is going to be a problem.

Whenever I’m helping a screenwriter or developing a script with a screenwriter and we’re deep in the weeds and we’re worried it’s not working, I always step back and remind myself, “As long as we get the characters right, we’ll be okay.”

Now what I do I mean when I say “root for?” Because that’s kind of vague. The way I see it is, if you can make us feel like your hero is a) a real person, b) a person who is fighting to better themselves, and c) place them amongst unfavorable circumstances that we would like them to get out of, that’s enough to get us to root for someone. As is the case with any screenwriting advice, this won’t work all the time. There are certain stories that need you to adjust the formula. But this covers the bulk of protagonists you’ll be writing in your screenplays.

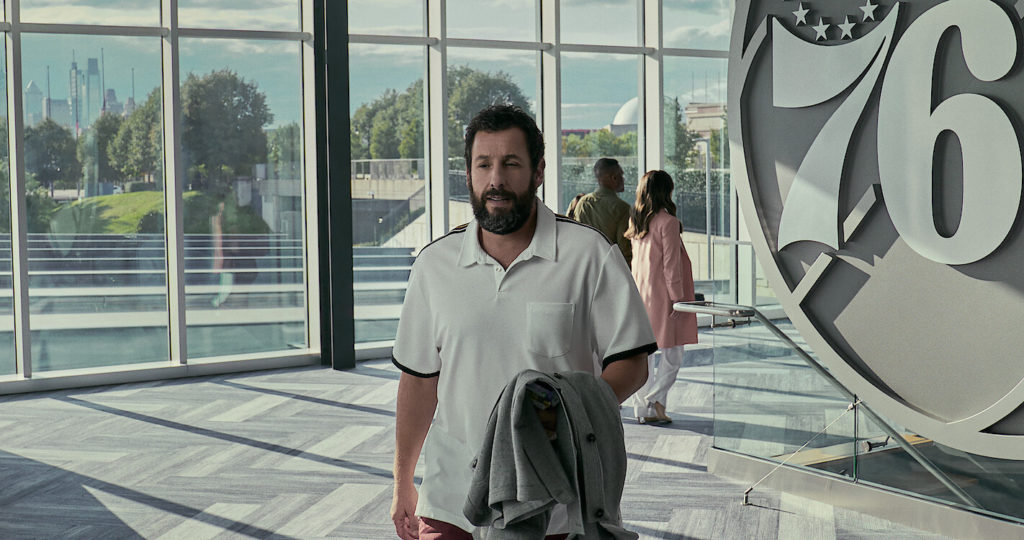

Which brings us to Stanley Sugarman, Adam Sandler’s scout character in “Hustle,” who I believe is one of the most well-crafted characters in sports history in so much as making the audience want to root for him. So let’s go over how they achieve this within the “root for” triumvirate.

By the way, if you haven’t seen the movie, it’s about a lifetime NBA scout (Stanley Sugarman) who’s running out of time to fulfill his dream of becoming an Assistant Coach who finds a once-in-a-lifetime prospect in Spain who he wants his team, the Philadelphia 76ers, to pick in the draft. When the brash new jerky Sixers president tells Stanley he’s not interested, Stanley quits the team and brings the player to the United States on his own dime in the hopes of getting him into the draft.

First off, Stanley feels like a real person. Nobody TELLS us that Stanley is a great scout. They SHOW us. They show him grinding. In Germany, in Spain, in China. Watching games in the farthest reaches of the world, looking for that one diamond in the rough.

We show him in airports, in hotels, coming back to Philadelphia, then going back out on the road again. Its’s an endless fruitless job. They show us his family – his wife, his daughter. They show him intelligently breaking down the top players he scouted in board room meetings. They have him saying jargon that only a NBA scouts would know.

All of this convinces us that Stanley is a REAL PERSON. If you don’t convince us of that, the other two things don’t work. We have to buy into this guy being real. If you get lazy and don’t do the work like Hustle did to show us that he’s really in this world, we’re turning your movie off at the 15 minute mark.

Next we have a person who’s fighting to better themselves. This is a key component to making us like a character. Cause we can have issues with people. We had issues with Louis Bloom. We had major issues with Arthur Fleck. But was there anybody else in the nightcrawler game who wanted to be better than Louis? While Arthur Fleck’s clown co-workers were fine playing kid’s parties, Arthur was busy planning his ascension in the stand-up comedy world.

Audiences like people who are trying to better their lives. Stanley Sugarman is 50 and he’s been doing this scouting thing his whole life. And he’s tired. He has every reason not to try. But he does. He keeps going out there, keeps grinding, keeps trying to find that one diamond.

And finally you have the negative circumstances surrounding your protagonist. You create negative circumstances because it gives the character somewhere to ascend to. If they’re already near the top, we don’t need to root that hard for them because they already have a good life.

Stanley is 50 years old and he’s still sleeping in Chinese hotels 20 hours away from his wife and daughter five nights a week. Talk about negative circumstances. (Spoiler) Right when Stanley gets his first official office with the Philadelphia Sixers, the owner who gave him the job dies the next day. Leaving his jerk son who doesn’t like Stanley to run the team. Talk about negative circumstances.

That simple one-two combo of making your hero someone with a big goal and then repeatedly punching them down, away from that goal, is like a screenwriting magic trick when you do it well. Because we like this guy. And we feel sorry for this guy. So of course we’re going to root for him.

Just to be clear, none of this means that, once you’ve done these things, you should phone your plot in. Because you’re never entirely sure if what you’ve done with your workers works. We can follow the rules and still write average characters, unfortunately. So you might as well try to make the rest of your script great as well. But getting that protagonist right solves so many potential issues down the road.

If you are someone who struggles with creating characters that readers root for, watch this movie. Even just watching the first act is enough. Cause that’s where you spend the bulk of your efforts on making the reader fall in love with your hero.