Genre: Comedy

Premise: (from IMDB) A series of bad investments forces a rich dysfunctional Midwest family to move to the sticks, seek out new friends and learn how to rely on each other.

About: “The Grigsby’s Go Broke” is one of a handful of unproduced scripts that John Hughes left behind, and the frontrunner to become John Hughes first posthumous film. For those who don’t know, Hughes dropped out of the University of Arizona in the late 1960s and began selling jokes to Joan Rivers and Rodney Dangerfield. He later became an advertising copywriter at Harper & Steers and then at Leo Burnett. He moved over to the National Lampoon magazine and penned a story called “Vacation ’58,” inspired by his family trips as a child. That story, of course, became the basis for “National Lampoon’s Vacation,” Hughes’ first big hit as a writer. After much success, in 1994, Hughes retired from the public eye and moved back to the Chicago area. He rarely gave interviews, save for promoting an independent film he wrote in 1999 called “Reach The Rock.” Although Hughes obviously made a lot of money in the business, it was a ridiculously sweet deal he got for Disney’s live-action “101 Dalmations,” which ensured that he’d “never have to work again.” He spent his later years farming, but did occasionally write under the pen name “Edmond Dantes.” While some say the pen name was because he wasn’t proud of the middle-of-the-road mainstream fair he was writing (Maid In Manhattan, Beethoven’s 5th, Drillbit Taylor), it’s unclear why he felt the need to write the movies in the first place, since, as pointed out, he didn’t need the money. It may be as simple as producer friends calling him and begging that he take a pass on their projects. Or maybe there’s another answer. I don’t know.

Writer: John Hughes

Details: March 2003, 2nd Draft – (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change greatly by the time of the film’s release. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft meant to further the education of screenwriters).

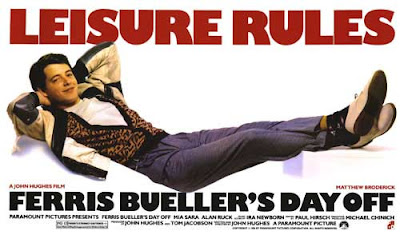

I feel like it’s my duty whenever I read a John Hughes script to point out just how amazing I think he is. “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off” is one of the top 5 comedies of all time. Hughes also wrote the great “National Lampoon’s Vacation,” “The Breakfast Club,” “Sixteen Candles,” “Planes, Trains And Automobiles,” and “Home Alone.” Like I mentioned in my review of one of his other unproduced scripts, “Tickets,” Hughes hit a chord with young audiences that had never been hit before, portraying teenagers with a darkness that separated his comedies from everything else that had come before them. It’s what made John Hughes John Hughes.

So I don’t know how that all changed. Somewhere along the way, Hughes clearly lost interest in the genre, eventually concentrating exclusively on light family fair. It’s been talked about a lot that John Candy was a good friend of his, and that his death took a huge toll on Hughes, which would make sense. 1994, the year Candy died, is the same year Hughes went back to Illinois and disappeared out of the spotlight. Maybe that death scared Hughes away from exploring the dark side of his material. Maybe a bunch of his original specs were rejected and he lost confidence in himself – forcing him into a series of studio assignments. I think that’s the most frustrating thing about all this, is I’m still not clear if Hughes left that world willingly or unwillingly. Does anybody know? Anybody out there?

Anyway, it’s this very mystery that gets me excited whenever an old John Hughes’ script pops up. And so while the idea behind “The Grigsby’s Go Broke,” isn’t necessarily my thing, Hughes made it an immediate must read.

When we meet Gary and Judith Grigsby, at one of their rich friends’ mansions, they are not described to us, but rather lumped in to one general description that paints each of these upper class suburbanites as “rich” and “well-groomed.” In addition to this strange choice, the Grigsbys do very little in their opening scene besides stand around and listen to other people talk. I’m a big believer in introducing your characters in an interesting way, or at the very least a way that tells us who they are. Lester Burnham in American beauty jacks off in the shower cause his wife won’t have sex with him, then pathetically spills the contents of his briefcase all over the sidewalk on his way to the car. I know who that character is. Watching two characters listen for four minutes doesn’t exactly give me a read on the couple I’ll be following for the next two hours, which was a frustrating way to start a script.

Later on, we meet the rest of the Grigsbys, who live in a mansion of their own. Judith and Gary have a 12 year old stuck up daughter named Wendy (who gets upset when the tempura on her private school’s lunch menu is too greasy), an 11 year old snobby son named Damon (who finds joy in making fun of public school kids), and a four year old anti-christ named Gracie (who orders around the maid and the nanny as if she were Mussolini). This is clearly a family who, because of their extreme wealth, has lost all connection with the real world.

Which is too bad, because things are about to get a lot more sucky for them. Mr. Economy sneaks up from behind and karate chops Gary and Judith’s jobs away. Which would be bad enough. But the Grigsby’s break one of the cardinal rules of being rich, which is to not live above your means! (actually, this is good advice for anybody, regardless of your income. In particular, me) In order to take care of all their outstanding payments, they end up selling everything they own, which leaves them with even less money than Screech. The Grigsbys must then move to an old real estate property Gary bought and forgot about in the neighboring working class town of “Mulletville.”

You’d think that having to write “Mulletville” in your return address would be punishment enough. But this is only the beginning. Wendy regrets dogging her soggy tempura since now her lunch menu consists of a meat the lunch lady can’t even identify. Gary, who used to own his own construction business, must now WORK construction. Poor Judith has to work in a department store, where her bitchy former rich friends come to routinely be bitchy to her. And let’s not forget about Gracie, whose days of having a maid fetch her grapefruit juice are long gone. Now she has to compete with the voice boxes of 20 other kids her age in a, gasp, PUBLIC PRE-SCHOOL!

While the story is pretty straight-forward and the theme is fairly obvious (does money lead to happiness?) there are some astute observations about the ice-cold communities of the rich vs. the supportive and community oriented neighborhoods of the working class. This contrast is played out nicely in a scene where the new neighbors try to surprise the Grigsby’s, digging into their toolbox unannounced in an attempt to fix up their house. The Grigsby’s, unaccustomed to such camaraderie, assume they’re being robbed and call the police.

But watching the characters face the challenges of their new worlds is a bag of mixed nuts. When Gary embraces his job with the work-ethic that made him so successful in the first place, it’s charming, while Damon’s attempts to make friends with the kids he used to scorn feels clumsy. Eventually, a nice (believable) twist gives the family the choice of going back to their old lifestyle or staying here in their new one. They’ve no doubt become better people through this experience, but our society teaches us that money is the end-all be-all. Whether it makes us happy or not, we’re told to grab it if it’s there. So will the Grigsby’s give in? Or have they grown enough to recognize that having everything doesn’t lead to happiness?

While this draft of The Grigsby’s Go Broke still seems to be finding its way, there are some good things about it. It starts with the sugar-coated dictator known as Gracie. Although she’s the world’s biggest 4 year old bitch, her nastiness is endlessly entertaining, which is why her scenes, which could have easily had you rolling your eyes, actually have you lol’ing the most. Also good is the second half of the screenplay, which really begins to shine once the numerous setups in the early part of the script start paying off. And once we hit page 70, we’re on the John Hughes Autobahn, which is good, cause there were times where I wondered if we’d ever leave first gear.

The bad is the way “Grigsbys” handles its characters in the first act, who all come off as nasty, annoying, or a combination of the two. I’m actually surprised Hughes took on such a story because its burdened with a couple of well-known screenwriting “avoid-if-you-cans.” Ages ago a producer said to me, “Don’t make your lead character rich. Audiences don’t identify with rich people.” I used to think that was the dumbest advice I’d ever heard. But in the years since, most of the time I’ve read or watched a rich protagonist onscreen, I realized I didn’t like them. It’s hard to feel sorry for a guy who has his Kleenex boxes stuffed with 100 dollar bills. A family of Richie Riches who take their money for granted then lose all of it? And I’m supposed to feel bad for them?

This is complicated even further by an even bigger no-no, which is to never make your protagonist an asshole. Nobody likes assholes. Nobody wants to root for an asshole. Go ahead, count how many movies you love where the protagonist is an asshole. Do you make it past your right hand? Do you make it past your index finger? And here, every one of the Grigsbys is a giant asshole! So now you have five protagonists who are all rich and all assholes. How do we get on board with that??

Well here’s the thing. Being an asshole is a legitimate and interesting character trait to explore. Because wherever we go on our planet, there are always going to be assholes. You probably work for one right now. It’s just that, most of the time, this role is explored on the antagonist’s side, and we can deal with that, because we always have our nice cuddly protagonist to go back to. But if everybody in the entire movie is an asshole, who do you lean on then?

This leads to a question I’ve asked a million times , but still haven’t received a satisfactory answer for. How do you make your protagonist a big fat dick and still have us, the audience, root for him? To my knowledge, it’s only been accomplished a few times. There’s A Christmas Carol of course. Some would say “Cool Hand Luke.” Although I’d argue that Paul Neuman is way too charming to be considered an asshole in that film. Even in a best case scenario, there are only a few precedents for it working. And even when it does work, it only seems to do so by a hair.

With Scrooge, we sympathize with him because early in the second act, we see that he used to be a good person. This “humanizing” of his bad behavior leads to our sympathy. However, had he had just one more scene screwing someone over, or had the Ghost Of Christmas Past showed up just five minutes later in the film, we may have solidified our opinion that Scrooge was a big bad douche and it didn’t matter what he did from now on, WE HATED HIM! You can see this mistake was made in remakes of the classic, where we don’t quite get on board with scrooge the way we did in the original film.

My point is, that while it’s possible to keep us invested in or even rooting for an unlikable protagonist, you stack the chips against you when you do it. And that’s what happened here in Grigsby’s. There’s something very alienating about these characters when they’re introduced to us, and that never quite goes away. Even when the script hits its stride, you never feel like you know these people.

The Grigsbys has its moments, and I hope to find later drafts of the script where I just know some of these issues have been taken care of, but this draft doesn’t quite have enough meat on the bone.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Don’t forget to entertain us in the first act! Most of Grigsby’s problems can be attributed to the first act. In addition to the character issues, there’s not enough excitement going on . The act is used strictly as a device to set up the characters and the inciting incident (them losing their wealth). Now I’m not criticizing Hughes because he may use his early drafts to get all the logical stuff in, then go back and add all the fun and emotion later. I know a lot of people who work this way. I only bring this up because it’s evident in this draft and I’ve been seeing it in a lot of amateur scripts lately. When you’re writing your first act, don’t get so caught up in setting up all the elements (plot, character, subplots, theme) that you forget to entertain your reader. First and foremost your job is to entertain. So make sure everything you set up in your story is done so in a way that entertains us. It’s very easy to lose sight of this priority, because of all the shit you gotta pack in the script early, but you can never lose sight of this.