Many years ago I went to one of those Screenwriting Expos.

I think that’s what it was called, actually – “The Screenwriting Expo.”

This was back in the day when the word “e-mail” was as buzzy as saying “TikTok.” “You’ve got mail” was as addictive a sound as the “ding” you hear when you get a new text. It was the original dopamine hit. In other words, it was a simpler time. And a world where the only screenwriting information you could get was from books and expos. So I was excited to be there.

However, the more I walked around the place, the more I realized it was nothing more than a giant excuse for bottom feeder industry types to hawk their wares and get you to sign up for classes or mentorships or newsletters you didn’t want to sign up for. I went from top of the world to ‘lost all faith in humanity’ in 60 minutes.

However, there was one teacher from the Expo I still remember. I don’t remember his name (for the purposes of this article, I’ll call him Jason). But what I do remember is that he was passionate, a stark contrast to the 200 other tricksters who leered at everyone as if they were giant walking wallets.

After everyone who’d signed up for the class arrived, Jason popped in a DVD of “Stand By Me,” and proceeded to pause it every so often to explain the screenwriting mechanisms that were going on underneath the surface.

It was instructional, effective, and fun, due to his outsized passion for the movie. I mean, I dug Stand By Me. But this guy really REALLY liked Stand By Me.

The part that he liked the most still sticks with me to this day. Jason went bonkers over Gordie’s midpoint story to his friends about a pie-eating contest. If you haven’t seen the film or don’t remember it, it’s about four 12-year-old friends who travel across the state to see a rumored dead body in the woods.

The scene in question occurs as the friends are taking a break and they ask Gordie (this is based on a Stephen King story so, of course, there has to be one writer in the mix) to tell them a story. We then cut out of the kids story and for EIGHT ENTIRE MINUTES we get a story THAT HAS NOTHING TO DO WITH ANYTHING ELSE IN THE MOVIE. I capitalize that because that’s what this teacher kept emphasizing.

“EIGHT MINUTES! EIGHT MINUTES THE STORY WENT ON! AND IT HAD NOTHING TO DO WITH ANYTHING ELSE IN THE MOVIE!”

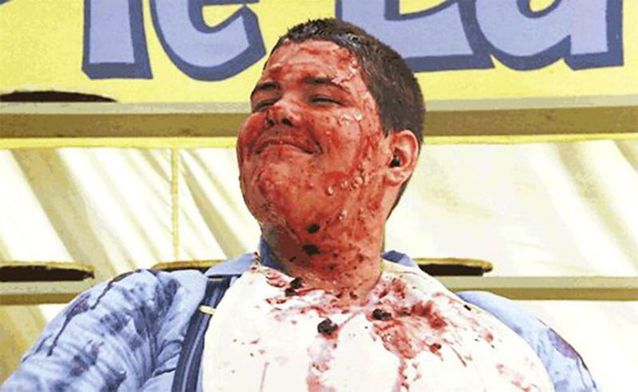

The story Gordie tells is funny. It’s about an overweight kid who enters a pie-eating contest and the experience is so overwhelming that, at the end of it, he throws up. That leads to the other contestants throwing up. Which then leads to the audience throwing up. Soon everybody is throwing up.

Jason kept hitting on the fact that you just “don’t do this.” You don’t stop your movie for eight minutes to introduce brand new characters and a brand new story that has nothing to do with anything else in the movie. If these characters were related to our heroes, you could justify it. If these characters somehow came back into the story later on, you could justify it. But none of that happens. It’s its own self-contained movie within a movie.

Jason was so obsessed with this little scene that, over the years, I’d find myself recalling the famed sequence and wondering why he’d gotten so worked up about it. His point seemed to be contradictory. He both loved the scene but was baffled that they’d included it. I couldn’t resolve what his message was.

Flash-forward to 2020. I’m reading a script just a few days ago from a very talented writer. He’d written a road trip movie and, during the script, one of the main characters tells a story that we flash back to. The story, like Stand By Me, was eight pages long. The story, like Stand By Me, wasn’t directly connected to anything else in the plot.

The flashback was pretty good, mainly because the writer was good. But as I weighed the flashback’s impact, I couldn’t help but realize it took up a full 10% of the screenplay. 1/10th of the script was dedicated to a story that wasn’t connected to the plot. What I mean by “not connected” is if you were to eliminate the flashback, nothing else in the script would have to be rewritten. That’s the easiest way to identify if something is necessary in your script or not. If you can get rid of it and you don’t need to make a single other change anywhere? It probably wasn’t a necessary scene.

Analyzing this sequence brought me back to Jason’s Stand By Me class. Because I finally understood what he meant. If a scene is not moving the story forward, it’s either a) pausing it, or b) moving it backwards. As a screenwriter, you want to avoid both of those things. Pausing and going backwards are antithetical to keeping an audience invested. Therefore, you should avoid them.

What Jason was saying was that the screenwriters for Stand By Me, Bruce Evans and Raynold Gideon, knew this. They understood that each scene must push the story forward. And that this pie eating story tangent wouldn’t do that. However, they decided that the scene was still worth it anyway. I suspect they felt it helped viewers understand Gordie better, since it showed how talented a storyteller he was and gave us some insight into him as a person (since you can get a feel for a person by the kind of stories they gravitate to).

As screenwriters, making sure every scene moves the story forward is one of the most important pieces of advice we can follow. The scripts that derail the quickest are the ones where too many scenes aren’t pushing the story forward. Think of it like a car ride. As long as you’re moving forward, you’re happy. But the second you get stopped in traffic. Or the second you get stuck behind a long stoplight, you start feeling anxiety. You didn’t get in the car to stop. You got in it to continually move forward until you got to your destination. A script read works the same way. If there’s too much stopping (scenes that don’t push the story forward), the reader gets anxious. And, at a certain point, that anxiety hits a breaking point. We’re out.

Of course, that doesn’t mean you can never write a scene/sequence that doesn’t move the story forward. Like the pie-eating contest. As long as you recognize that it’s a gamble and that, therefore, the scene has to be amazing, you should be okay. Just don’t make a habit out of including these scenes. Jason was quick to point out that every other scene in the movie pushed the story forward.