I’ve been working hard on my dialogue book.

One of the most frustrating things about writing the book has been finding recent movies with good dialogue to reference! Most great feature film dialogue went out the window in the early 2000s with the death of the indie film. If any of you have suggestions for good dialogue movies post-2015, I’d love to hear them in the comments.

For this reason, I decided to go in the opposite direction and throw in one of the most famous dialogue movies of all time and one I’m not intimately familiar with – Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf. I think I even did an article about this movie years ago but I don’t remember a lot from the film other than the characters all seemed very angry.

Rewatching it was strange because I’ve been writing all of these dialogue tips in my book, believing they were inarguable, only to realize after Virginia Woolf, that there’s more to this dialogue thing than meets the eye.

A rule I was absolutely certain of was that, going into a scene, at least one character needed to have a goal. I didn’t think dialogue could survive without that. Because, otherwise, people are just talking to fill in the space. There’s no purpose to what they’re saying.

Well, with Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, which is about an aging couple who works at a prestigious university and a young couple who come by for some late-night socializing – I realized that this divine dialogue truth wasn’t as universal as I thought.

The characters here would often speak without a clear goal, and for long periods of time. In fact, there were even moments where characters only spoke to break the silence. I mean I guess you can say that “breaking the silence” is a goal, so maybe my precious rule is still in tact. But I didn’t think that a scene could survive when the goal was that weak.

As I continued to watch the movie, I realized that there was one dialogue truth that is always present – and that is CONFLICT.

This whole movie is slathered in conflict. There isn’t a single frame that doesn’t have it. So even though the characters are not always speaking with purpose, the dialogue is still entertaining due to the fact that conflict is present.

And it’s conflict on multiple levels, which I think is the reason it’s able to be so good in spite of its lack of clear goals. If you’re doubling up on conflict, that extra dose could be the substitute you need for a goal-less scene.

What do you mean “doubling up,” Carson?

For starters, the central married couple, Martha and George, hate each other. She hates him because he’s not enough of a man (by the way, this is the first fictional story I know of that implores the insult, “Simp”). And he hates her because she’s constantly cruel to him (not to mention, her college president father’s superior presence always hangs over him).

This creates the undercurrent of tension in every scene. It is, what most people refer to as, “subtext.” Even without saying anything, they’re already saying stuff.

Then this young couple comes along with their perfect young bodies and whole life in front of them and it just sets George off. He uses them, then, to spit out various levels of provocation and frustration. That’s where the second level of conflict is occurring – on the surface.

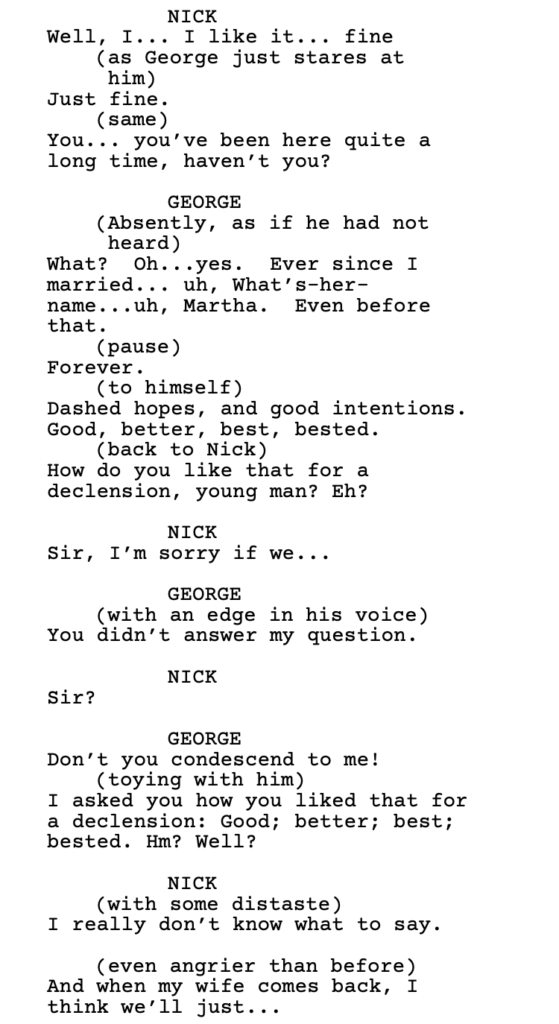

This doubling down ensures that every line of dialogue has bite to it. Here’s a scene from early on in the movie where Nick, the young professor, is starting to get prickly in response to George’s aggression…

I think the issue I’m grappling with here is that while there isn’t an obvious purpose to George’s interaction with Nick – George is not, for example, trying to get Nick to invest in a business venture of his – I’m wondering if there’s some directive to this conversation that can be quantified, and therefore taught.

George is obviously riling Nick up. That is his internal “goal” in the moment. But why? And is it something that I should be teaching writers to do? Have their characters start sh@# with other characters for no reason. Yes, you get conflict-heavy dialogue. But it’s without structure, without a point.

I think that Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf pushes up against that older belief that movie dialogue should mirror real-life dialogue. In real life, people are mean to other people because they hate themselves or hate their life and they’re just stirring the pot to stir it. They don’t have some divine goal in the moment other than to spew out their thoughts and hurt someone else.

Even as I’m writing that, I go back to this idea of: well, maybe all good dialogue does have a goal, then. Because isn’t trying to hurt someone with your words a goal?

In digging a little deeper, I noticed that while there isn’t some big goal George is trying to achieve, he is a LEADER. He is pushing the scene forward. And that’s worth bringing attention to. Because maybe the real baseline to good dialogue is that someone is pushing the scene forward. George is a force here. He is trying to agitate and aggravate Nick. We’re then curious to see if Nick will crack or fight back. Maybe that’s enough.

What you don’t want in a scene is two characters who are passive. The only thing worse than one character who tries to stir sh#@ up for no reason is zero characters who try to stir sh@# up for no reason because then the scene is lifeless.

Another complication to figuring out this odd movie is that it was originally a play. In plays, you have to fill up 90 minutes of talking somehow. Movies are more visual, which allows you to do more showing than telling. So is this just a case of a playwright filling up space with dialogue cause he has to? Dialogue that wouldn’t normally be in a movie?

I’m going to keep working on this because it’s my belief that the best dialogue has purpose. And that purpose comes from a character who has some sort of goal or “want” in the scene. I may have to dig deeper into Virginia Woolf to see if the film is, indeed, achieving this and I’m just missing it, or if there are deeper secrets yet for me to learn about dialogue.

In the meantime, feel free to provide your own thoughts on this movie, your own suggestions on good dialogue movies post-2015 from screenwriters not named Tarantino (I’ve got enough of him in the book). Share your own dialogue tips. And leave suggestions on what aspects of dialogue you want explored in the book. Feel free to share your dialogue struggles as well. The more I know about what perplexes you guys, the better I can make the book.

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf is on HBO Max.

$50 OFF A SCRIPTSHADOW SCREENPLAY CONSULTATION! – The Labor Day deal may be over but you can still save some money on a script consultation! I have a 4 page notes package or a more detailed 8 page option designed to both fix your script and improve your writing. I also give feedback on loglines (just $25!), outlines, synopses, first acts, or any aspect of screenwriting you need help with. This includes Zoom calls discussing anything from talking through your script to getting advice on how to break into the industry. If you’re interested, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and let’s set something up!