We’ve just watched a movie make more money at the box office than any other movie in history. There’s a movie in theaters shot by one of the world’s best directors and starring one of the best actors that has garnered multiple Academy Award nominations (The Revenant). We’re a month and a half away from two of the biggest superhero films in history, Batman vs. Superman and Captain America: Civil War.

For those who would rather view their entertainment in the comfort of their own home, Netflix has offered its customers a variety of enormously budgeted high profile shows, including House of Cards, Daredevil, and Jessica Jones. It seems wherever you go, there’s tons of entertainment to choose from.

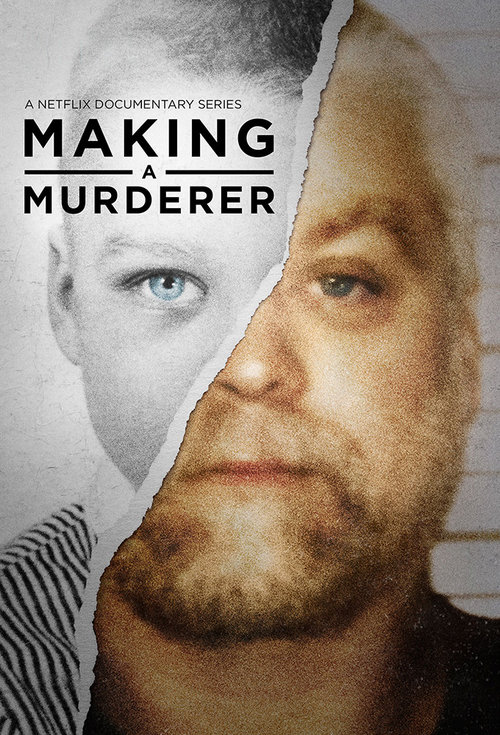

And yet despite this, when I run into people outside of the movie world, normal people on the street, they all only want to talk about one thing: Making A Murderer. It’s become such a part of the cultural lexicon that “Have you seen Making a Murderer?” is officially the new, “What’s up?”

When anything breaks out of its genre space and becomes a universally known phenomenon, every screenwriter serious about this craft need stand up and pay attention. The world is telling you what people respond to (I believe this to be true for TV, movies, songs, plays, any form of entertainment). And so today, I wanted to look at this show to see if we could glean any screenwriting lessons from it.

Before we start, however, I’ll offer my quick opinions on the show, since everybody has one. Spoilers follow throughout the post, of course. Personally, I think Steven Avery is guilty. I believe the show leaves out a bunch of crucial pieces of information on the prosecution’s side in order to make Steven a more sympathetic protagonist. And when you think about it, they had no choice. If anyone was certain that Steven committed this crime, the entire documentary implodes. We have to want to root for the guy for everything to work. The filmmakers knew this, and so strategically withheld key pieces of evidence so that we’d side with Avery.

As far as documenting a real life case where you’re supposed to be impartial, this was a slimy move. But if you’re looking at this as pure entertainment, it was a genius move, because, again, we want to root for this guy. We want to believe the system is corrupt. We want to see that system go down. And that’s the first of a few lessons Making a Murderer can teach us in regards to screenwriting.

I want to go through five storytelling lessons derived from this series that we can apply to our own screenplays, to give them a similar chance to break out and become mainstream hits.

1) The system makes you play by one set of rules, while they get to play by another (aka “corruption”) – This setup ALWAYS WORKS folks. As members of society who are constantly nickled and dimed by the system (taxes on everything, parking tickets for being a minute late to your car, police harassment), when that very system makes a mistake and doesn’t cop to it? It makes our blood boil. We want them to pay just like we’ve had to pay our whole lives. This is the crux of why Making a Murderer works. These guys screwed up by putting an innocent man in prison, and then, to avoid paying for it, they framed him for murder.

2) We hate bullies – It doesn’t matter if it’s the bully at the schoolyard or a giant corporation throwing all its legal resources to bury the little guy who’s come up with a better way to do what they do. We hate when the big guy picks on the little guy. And that’s why we react so strongly to the state bullying Steven Avery.

3) We love the underdog – We always root for the underdog. And the more of an underdog they are, the more we’ll root for them. A simple and powerful way to come up with a story is to start with a small fry being pitted against a giant fry.

4) Wrongly accused – We HATE when our main character has been wrongly accused. We want to scream out to the system, “They’re innocent!” Harrison Ford and The Fugitive started this trend back in the 90s and it hasn’t failed to deliver since. We’ll always get heated when someone who’s innocent is thrown in prison.

5) Add a twist to your murder-mystery – This is probably the most important tip coming out of this show. Murder is everywhere in storytelling. But a dead body and a few suspects is too generic. We’ve seen that setup too many times already. You have to find a twist that makes your murder-mystery FRESH. The genius of Making A Murderer is its unique twist on the genre. What if someone who was accused of murder had already spent years in prison for a crime they didn’t commit? That adds a whole new dimension to the murder, one that makes you prone to believe the man, no matter how extensively the evidence is stacked against him.

When you put all these things together, you can see why this show has taken off. For me, the first 5 episodes of the show were genius. I loved 6-8 as well. But I found myself passively watching once I got to 9 and 10. I’m a huge believer that when you hit the end of your main character’s plight, the story’s over. And after episode 8, we knew Steven Avery’s fate. The stuff with his son or nephew or whatever (the focus of 9 and 10) was never that interesting to me. He wasn’t as sympathetic of a character. I know he was taken advantage of but for some reason I didn’t care. And just from a storytelling perspective, you want to wrap up your secondary character’s storyline before you wrap up your main character’s storyline. Making a Murderer did it the opposite way, sending the show out on a whimper instead of a bang. What did you guys think?