The longer I do this, the more convinced I become that the “in the moment” story is more important than the overall story. What do I mean by that? As long as the story going on in the current scene is entertaining, you’re going to keep the reader hooked. Because if I’m entertained by the first scene and then I’m entertained by the second scene and then I’m entertained by the third scene, and so on and so forth, I’m going to want to keep turning the pages until the script is done.

However, if the individual scenes are hit or miss (I’m entertained by the first scene, I’m bored by the second scene, I’m kinda entertained by the third scene, I’m bored again by the fourth scene) it won’t matter how good the overall story is. Because the pieces within that story are struggling to keep my attention. And as anyone who’s read scripts knows, we don’t finish reading scripts like that.

This begs the question, how do you make each and every scene entertaining? Who out there has the ability to write a good scene EVERY TIME OUT? Isn’t that an impossible standard to live up to? If you’re going by the odds, some of your scenes have to be bad. Right?

Wrong.

This is a toxic way to think.

While it’s true that not every scene can be great – even scenes from some of our favorite movies suck – there’s a method you can use to ensure that your scenes will rarely, if ever, be bad. And by using this method, your likelihood of writing a good scene goes up exponentially.

The method I’m talking about is built around the idea of CONFLICT.

Now we’ve been told ad infinitum that our scenes need conflict. The problem with this advice is that that word is vague and unhelpful when you’re constructing a scene out of thin air. So I’m going to help you see conflict in a new way. And this way should help your scene-writing dramatically.

From now on, I want you to look at every scene as requiring a POSITIVE CHARGE and a NEGATIVE CHARGE. If you live by this simple rule, every scene you write is going to have conflict. Conflict, of course, naturally results in drama. And drama is the magical component that ENTERTAINS audiences.

Let’s look at the simplest version of this – positive character, negative character.

If you watch a movie like Fury Road, you have lots of scenes with your positive charge character, Furiosa – she’s trying to save a group of people – going up against your negative charge character, Mad Max – who’s trying to escape. Every scene between these two characters is entertaining because those opposing charges are always on display.

This is a great way to ensure that most of your scenes will be entertaining. You simply take the two characters who are going to be around each other the most in your movie and you assign one of them a permanent positive charge and the other a permanent negative charge. This guarantees that every scene these two are in is going to have some level of conflict, which is why the scene will probably be good.

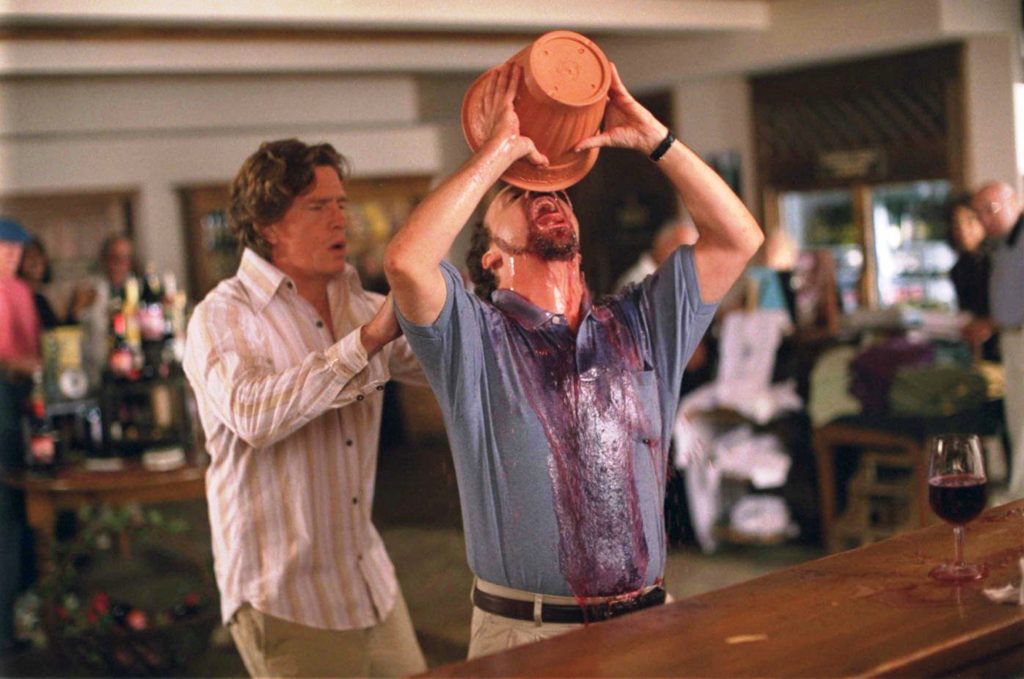

This can work especially well if your narrative is purposefully flat. A great example of this would be the movie Sideways, which follows two friends up to Napa Valley for the weekend. It’s not a plot movie by any means. But the two friends were Jack (positive charge) and Miles (negative charge). Their essence as humans was so embedded in that positive or negative belief system that they didn’t need plot to be entertaining. They just needed to be around each other.

Unfortunately, not all of us are interested in writing buddy cop movies or road trip movies. Which puts you in a more difficult position. Because now instead of the positive and negative charges automatically being there for you in every scene, each scene requires you to find a new positive and negative charge.

This is where screenwriting gets tough. Because each scene becomes a unique challenge to find the charges. And if you’re lazy, you won’t bother doing so. But luckily you have me and I can give you some direction. The second type of positive-negative charge is TEMPORARY CHARGES.

In this scenario, your characters may or may not be carrying permanent positive or negative charges, which means the scene itself must be constructed in a way to give each character in the scene a positive and negative charge.

The most obvious example of this is Character A is mad at Character B about something and lets them have it. Character A is our negative charge (he’s mad!). Character B is our positive charge (he’s trying to defend himself and calm A down). To be clear, Character A may be a positive person throughout the rest of the script, but right now he’s mad, so he becomes the negative charge for the scene. That’s the thing with temporary charges. You can construct them for the moment. They don’t need to be attached to the character’s permanent identity if the scenario calls for it.

But anger isn’t the only negative charge in your Charge Arsenal. I recently watched a movie called Red Rocket. A great film. It’s going to be one of my favorite films of the year. It’s about a former porn star, Mikey, who moves back to his Texas hometown with no money. One of the early scenes has him going to Leondria, a drug dealer, to see if he can sell weed for her.

This is a very simple example of a temporary positive charge temporary negative charge scene. Mikey is the positive charge. He’s trying to get something to better his life – make money so he can move back to Los Angeles. And Leondria is the negative charge. She’s suspicious of Mikey. She’s also potentially dangerous. She doesn’t really want him selling for her. That’s what makes the scene entertaining, is the positive charge being forced to interact with the negative charge.

And by the way, if you want to see a masterclass in positive-negative charges, go watch Fargo (the film). The reason almost every scene in that movie is a classic is because that’s all the Coens focused on back then, was positive and negative charges.

Okay, let’s get a little more nuanced now. Let’s say that you have two characters who get along. Which means, in the majority of their scenes together, they’re both going to be positive charges. This will usually happen when two characters fall in love. So now what? How do we create conflict if two people are on the same page?

Simple. We introduce a negative charge EXTERNALLY. Romeo and Juliet is the perfect example of this. Romeo and Juliet are both positive charges. But their families are both negative charges. Which means you just have to bring a family member (negative charge) into a scene to create conflict. Or, in some cases, just the threat of Romeo and Juliet being caught out with each other can be a negative charge. Think about it. These two aren’t hanging out without a care in the world. They’re hanging out always having to look over their shoulders. Why? Because behind their shoulders is that looming negative charge.

This is what James Cameron did with Titanic as well. At first, Jack and Rose were opposing charges. He was positive (trying to get her) and she was negative (she was resisting). But once they got together, they both became positive. And that meant Cameron had to create a series of external negative charges to keep their scenes entertaining. He did this with Cal Hockley, Rose’s fiancé. He did this with Hockley’s undertaker assistant, who chased them around. And he eventually did it with the ship itself – the sinking and all the problems it created were the primary negative charge in many of their scenes.

Now here’s a question for you. What if you only have one character in a scene and he’s not in a scenario where he’s opposite a negative charge? How do you create the necessary conflict to ensure an entertaining experience for the viewer? This is where writing gets fun. You create the charge FROM WITHIN. One charge will be the external and the other charge will be the internal.

So let’s take a look at Arthur Fleck, the Joker. The reason that Arthur looking in a mirror can be a compelling scene all on its own is because externally he’s struggling to be happy (negative charge). Yet internally, he’s desperate to be happy (positive charge). Which is why he’s shoving his fingers into the sides of his mouth and forcing them up. He wants to smile but he can’t.

If the Joker were to smile and there was no resistance at all, there’d be no conflict. So the scene wouldn’t be dramatic. Hence, the importance of opposing charges.

All of this boils down to when you’re in a scene, ask yourself, where is the positive charge coming from and where is the negative charge coming from? If you have that in place, there’s a good chance you’ll write an entertaining scene. The reason I say “good chance” and not “guaranteed” is because screenwriting is composed of too many variables that affect each scene.

Take a look at the Obi-Wan Kenobi show. Many of the scenes in the second episode followed the rules I laid out above. They have Obi-Wan in them, our positive charge (he’s rescuing Baby Leia), and Baby Leia, who represents our negative charge (she resists his help and is not thankful). These scenes should work according to me. Both characters have an inherent opposing charge. Why, then, do the scenes suck? They suck because Baby Leia is a poorly written character. We don’t like her. We don’t want to be around her. Even the most well-constructed version of conflict in a scene will fail if we don’t like (or are interested in, or care about) one of the characters in the scene.

So obviously, other parts of your screenplay need to be on point. But at least now you know that if you inject that positive and negative charge into every scene, there’s a good chance you’ll write a dramatic scene. And since drama equates to entertainment, we’re going to be invested in each and every one of your scenes. Go forth and try this in your current script and watch how much better your scenes get.