The creator of HBO’s hit, “The Night Of,” sets his sights on a famous serial killer in an attempt to finally give the best selling series of “Ripley” novels the adaptation they deserve.

Genre: TV Pilot – Drama

Premise: A young frustrated con artist barely making ends meet in New York City is given the opportunity to seek out an old friend in Italy, an old friend who gives him an opportunity to step into the high life.

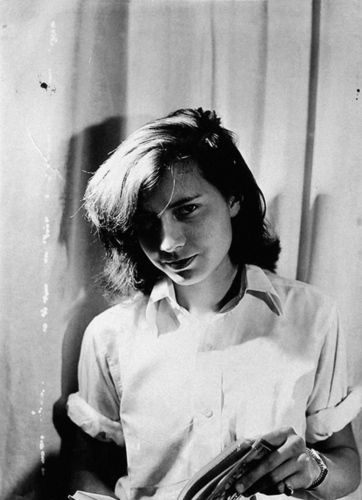

About: This is Steve Zallian’s big new project. He’s writing and directing many of the episodes in the first season. Zallian most recently penned The Irishman script. — A bit of an aside here. I am not a lover of biopics by any means, especially biopics about writers (I find the act of writing cinematically boring). But if you’re someone who likes that sort of thing, consider writing your next biopic on author Patricia Highsmith, as she was a fascinating figure. Early on in life, her mom told her that she’d tried to chemically abort her. This led to a lifetime of depression and alcoholism, and informs a lot of Highsmith’s writing, particularly with Ripley, who is detached from the world and mostly detests humanity. She was a lesbian who, at one point, fell in love with and had a relationship with a gay man. She seemed to have inherited many of her mother’s worst traits as she got older, and was said by many to be intolerable. An interesting character study for sure.

Writer: Steve Zallian – Based on the novels by Patricia Highsmith

Details: 58 pages (EP 1, Draft 5, June 20, 2019)

Do you remember 1999’s Talented Mr. Ripley? If so, pat yourself on the back as you’re one of a dozen people. The underwhelming film was known more for its hair, makeup, and costuming than its story. In fact, 20 years later and the only thing I can remember about it is Matt Damon standing on the beach wearing shorts that were too tight. Not sure what that says about me but luckily this isn’t about me.

It’s about trying to achieve one of the hardest tricks in screenwriting: writing inaccessible characters that audiences want to follow.

Tom Ripley is a cold friend-less angry individual. The closest thing 1961 had to an incel. Except, back then, there was no internet. There wasn’t a security camera poking outside every New York pizza joint. That meant you could hide a lot easier. And that’s what Tom Ripley does best. He hides.

That’s because Tom rips off old people with his “overdo bill notice” scam, an elaborate concoction that involves stealing mail so that old people don’t get bill notices, then calling them and demanding they send the overdue money now. Of course, the address they send them to is his own. Yeah, back in the 60s you could get away with all sorts of crap.

But Tom hates his life. He hates piecing together this pitiful existence. He hates the inexpensive clothes he wears. His weak-sauce haircut. His poor man’s shoes.

One day, one of the many people looking for Tom finally finds him. But they don’t want to beat him up or put him in jail. They have a message for him. A man named Herbert Greenleaf wants to meet you. He wants to offer you a job.

Tom goes and meets the surprisingly rich Herbert, who informs him that Tom is a friend of his son, Dickie. Tom barely knows Dickie but nods anyways cause this sounds like it’s going to be lucrative. Herbert explains that Dickie has become a trust fund baby, doing nothing with his life but enjoying himself on the beaches of Italy. Dickie is easily influenced by his friends so he thinks if one of his friends goes to talk to him, they could convince him of coming back to the States.

Tom is paid handsomely for the job, given 1500 dollars plus expenses! Unfortunately, Tom has to take a boat to get there. And Tom’s biggest fear is drowning. But he makes it across the Atlantic in one piece and soon he finds the small beautiful seaside Italian town where Dickie is staying.

And what do you know! There he is, right on the beach, easy to spot as the lone American with the American girlfriend. Tom walks up to Dickie. “Dickie!? Is that you?” Dickie has no idea who Tom is. But, you see, in the 60s, when someone says they know you, you nod and start talking to him. Which Dickie does, albeit reluctantly.

During their interaction, Tom realizes that Dickie detests him. Not just detests him, but believes he’s beneath him. Which is the thing that Tom hates most about being Tom Ripley. Being a nobody. But that’s okay. Because there’s something Tom really likes about Dickie. And that’s the power of being a rich American without any responsibilities. Tom makes the decision right then and there – He wants to be Dickie Greenleaf. End of pilot.

The problem with serial killer main characters is most people can’t sympathize with them. Especially characters like Tom Ripley. This guy hates everyone. He rips off old people. He does reprehensible things yet believes he’s above others. How do we get on board with that?

Well, one of the reasons the novels were able to make that work is that novels allow you to get inside the head of the main character. You can hear his rationalizations. You can hear his moment to moment thought-process for why he does what he does. You might not agree with what he does. But at least you’re given an entry-point into why this person acts the way they do.

You don’t see that in screenplays or movies where we aren’t privy to the internal monologue. All we know about Tom is through what he says and what he does. And since Tom is a duplicitous person, he rarely says what he’s thinking to people. Instead, he says whatever he needs to say to manipulate them. That means trying to find any reason to like this character is difficult.

And you can see Zallian struggling with that. He spends most of the time writing his action lines like a novel. For example, here’s what he says when Tom is on the ship to Italy: “He passes people reclined on deck chairs, reading, others playing shuffleboard, others strolling past him. In truth, he doesn’t really want to meet any of them. Who he might be in their imaginations is more satisfying to him than who they might discover him actually to be.”

That’s some great character insight. Unfortunately, it ain’t going to be there when this scene plays on screen.

Despite this, Zallian figures out a way to keep us invested.

In the very first scene, Tom is sitting on a subway car, hating his life: “As the train pitches through its tunnel under the city, light bulbs overhead blink off and on taking photographs, as it were, of his fellow passengers on their hopeless journey in this carriage to hell. Most repulse him. The rest bore him. People, okay, with lives and ancestries, perhaps even interesting ones, though Tom doubts it.”

Then, their train car starts running parallel with another train car. And, in that train car is a large man with a big bushy mustache who seems to be staring straight at Tom. It unnerves him so Tom gets up to walk to the next car. But as he does this, the mustached man follows. The man has an uncanny ability to stay with Tom, no matter how hard he tries to ditch him. And the next stop is coming up quickly. Which means he’ll have to make a run for it.

The reason I bring this up is because most writers would’ve stopped at the “observing the world” part. They would have bathed the scene in more passages about how awful the train car and people were. But Zallian understands that the reader demands SOMETHING HAPPEN. Drama is like air to stories. You can hold your breath for a while. But sooner or later, if you want to live, you have to breathe. Stories need drama constantly popping up.

Zallian is really talented in that area. He knows how to move stories forward. And this was one of his biggest challenges. If you zoom out of this pilot, not a whole lot “happens.” We establish Tom’s life in New York. He goes on a long boat trip. He gets a room in a small Italian town. And only in the last ten pages does he speak to the person who’s going to kick-start the series.

However, Zallian cleverly squeezes in small dramatic beats that keep us alert, keep us wondering what’ll happen. Tom Ripley doesn’t just go to the bar and have a drink. He goes to the bar and notices a couple of men at the end of the bar looking his way. What are they looking his way for? Do they want something? Are they one of the many people looking for him due to a scam he pulled? This creates conflict, tension, suspense. So we’re willing to stick with the story even if it’s devoid of major plot beats.

“Ripley” will be a huge challenge for Zallian – there’s no doubt about that. He’ll be able to dangle little carrots at us for a while. But sooner or later, we’re going to need a reason to want a follow an inaccessible depressing sociopathic serial killer. The good news is, if there’s anyone who can pull that off, it’s this writer.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you want to write a scene that doesn’t move the story forward, it only informs us about the character, then make sure we’re PHYSICALLY MOVING SOMEWHERE. I noticed when Tom Ripley got on the boat to Italy that we stayed with him during the entire boat ride even though we didn’t have to. A lot of writers would cut to Italy. But Zallian wanted to use that time to tell us about the character. The way he saw rich people. How Ripley, himself, wanted to be rich. Normally, when you’re writing scenes that only inform the reader about character, they’re boring. The reader says, “What’s the point?” However, you can get away with this if we’re physically moving towards the next goal post. This wouldn’t have worked had Ripley been walking around New York noticing people. It works because we know we’re physically on our way to Italy where the next plot point is.

–