A hot topic after yesterday’s review was how the script was driven by “ex special forces” characters. I read a variety of comments that said something akin to, “Whenever I see “ex” anything in the logline, I’m out.” The consensus was that this was a lazy cliche writing choice that demonstrated an utter lack of imagination. To this I say, “I feel ya.” You can probably find some early reviews on the site with me railing against this very issue. But in time, I’ve come to change my mind. And I want to explain why.

The number one reason you want to use an ex-special forces, or ex-detective, or even active versions of these characters in your screenplay, is that it makes your script a hundred times more marketable. There is no genre Hollywood knows how to market better than “guy with a gun.”

I’ll never forget when this clicked for me. I was reading an interview with Joel Silver, who had talked to Robert Downey Jr., and Downey Jr. was lamenting the fact that he couldn’t break into the larger blockbuster scene. Silver said, as if obviously, “Well yeah, it’s because you’ve never had a gun in your hand in a movie.” In the next movie (“Kiss Kiss Bang Bang”), Downey Jr. strapped up, and it wouldn’t be long before he became one of the biggest movie stars in the world.

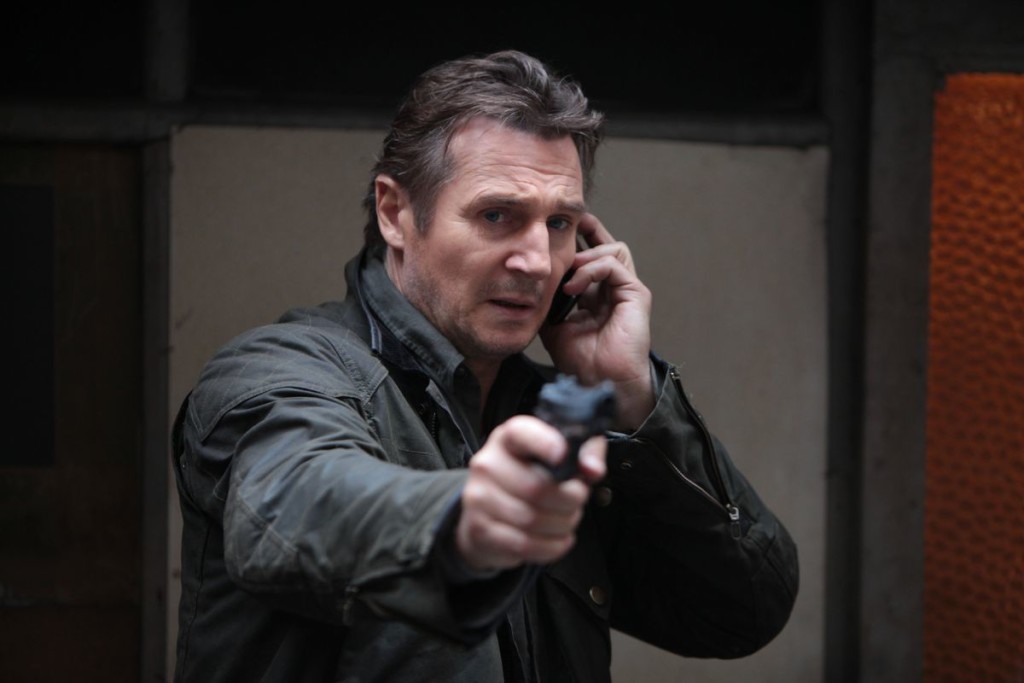

You could make the same case for Liam Neeson. Neeson has had a great career. But he didn’t become a household name until his ex special forces character with a particular set of skills, Bryan Mills, flew to France to save his daughter.

I can already hear you saying, “But isn’t it much more original and interesting if the hero DOESN’T possess a particular set of skills?” Not only does he become a bigger underdog, but if he’s not proficient with a gun, he has to use his wits and creativity to get out of situations. That’s so much more interesting than “bam bam, you’re dead.”

There’s some truth to this statement but here’s the thing. You’re limited in how extreme of a situation you can place a character in if they don’t possess the skills to survive that situation. Take John Wick. If John Wick is just a normal guy, he’s dead by the 20 minute mark. You can’t go up against a trained Russian syndicate if you’re a nobody who’s never pulled a trigger before. Any version of that story that has our untrained hero defeating the Russian syndicate is a bold-faced manipulation. And that’s the real issue here. The less skilled your hero is, the less skilled the opposition must be for it to be believable, and, by association, the smaller and less marketable your movie becomes.

The exemption to this rule is the “run away” narrative. You used to see this a lot in conspiracy thrillers like Enemy of the State. Because the “normal everyday guy” didn’t have the skills to go toe-to-toe with his government trained pursuers, he would run away. And the whole movie, then, would become running. As exciting as some of these films have been, a situation where a character runs away is never as compelling as a situation where a character stands his ground. And you can’t stand your ground if you don’t know how. Remember, guys, you’re going up against SUPER HEROES these days. The coolest and most badass characters cinema has ever seen. The ONLY type of character who can compete against this at the box office is a REAL LIFE SUPERHERO – James Bond and Ethan Hunt and ex special forces dudes such as our heroes in Triple Frontier.

So the question you should be asking isn’t, “How can I have my plumber protagonist believably defeat the Chinese mafia?” It should be, “How can I make an age-old character trope interesting, different, fresh, or all of the above?”

Levres offered up the first answer to this, which is that you can camouflage the cliche-ness of your hero’s background if you place them in a fresh situation. In other words, if you place a bunch of ex navy seals on a mission in Iraq to kill a terrorist, we’re not going to be excited about that. It’s too familiar. But a bunch of ex navy seals being forced to save a high-profile politician who’s been taken hostage with his family by a terrorist inside Disney World? That feels different. It’s a key reason why Triple Frontier worked. The unique locale helped offset the ex-special forces cliche.

But the secret sauce in winning this war is in the character construction. If you write a good character, it doesn’t matter what job they have. It doesn’t matter if they’re the most cliche archetype there is. If you can make them likable, if you can make them relatable, if you can provide them with depth, if you can give them personality, if you can give them a flaw they’re battling, we’re not going to be thinking about their jobs. We’re going to be thinking about them.

So if you’re one of these writers who’s writing an ex-Navy SEAL, your first order of business is to construct a character we like, and look for ways to make them different. Because what critics are really saying when they say, “I hate ex-Special Forces characters,” is “I hate generic ex-Special Forces characters.” One of the best scripts I’ve ever read, The Equalizer, had ex-agent Robert McCall helping an overweight co-worker eat properly so he could pass a fitness test in order to make security guard. Later, we find McCall reading The Old Man and the Sea (he’s attempting to read all 50 books from the “The 50 Books You Must Read Before You Die” list) in a diner. This guy’s a little different. This ensures that we don’t think about the cliche nature of his former job.

Finally, if you’re writing “cliche” main characters like ex-NAVY SEALS, take some chances with your narrative. The idea here is if you’re going to play it safe in one area, you need to take chances in other areas. Because you can’t completely avoid cliche in a movie. It’s impossible. But you can minimize it. I brought this up with Triple Frontier yesterday. I loved how after they rob the house, the final 50 pages cover the logistical nightmare of trying to transfer 600 million dollars out of Paraguay. I’d never seen that before. If you can make narrative choices that give us things we’ve never seen before, they’re going to cancel out the things we have.

Now I’m not saying there’s no way to write a movie where an average guy defeats an organization of trained men. The Matrix figured out a way to do it. But if you can’t find that elusive Matrix-like idea, it’s still possible to write a good movie with cliche FBI agents or cliche ex-special forces agents. Just put them in a new situation, give us characters we care about, and take some chances with the narrative. You’ll be good. :)