Yesterday, we discussed the drudgery of formulaic writing via Rob Liefeld’s 2 million dollar monstrosity, “The Mark.” Today, I’m going to thank Andrea Moss for pointing me to Seth Sherwood’s tweet thread, which takes on the current industry formula for writing “elevated horror.” Sherwood is probably best known for writing 2017’s, “Leatherface.”

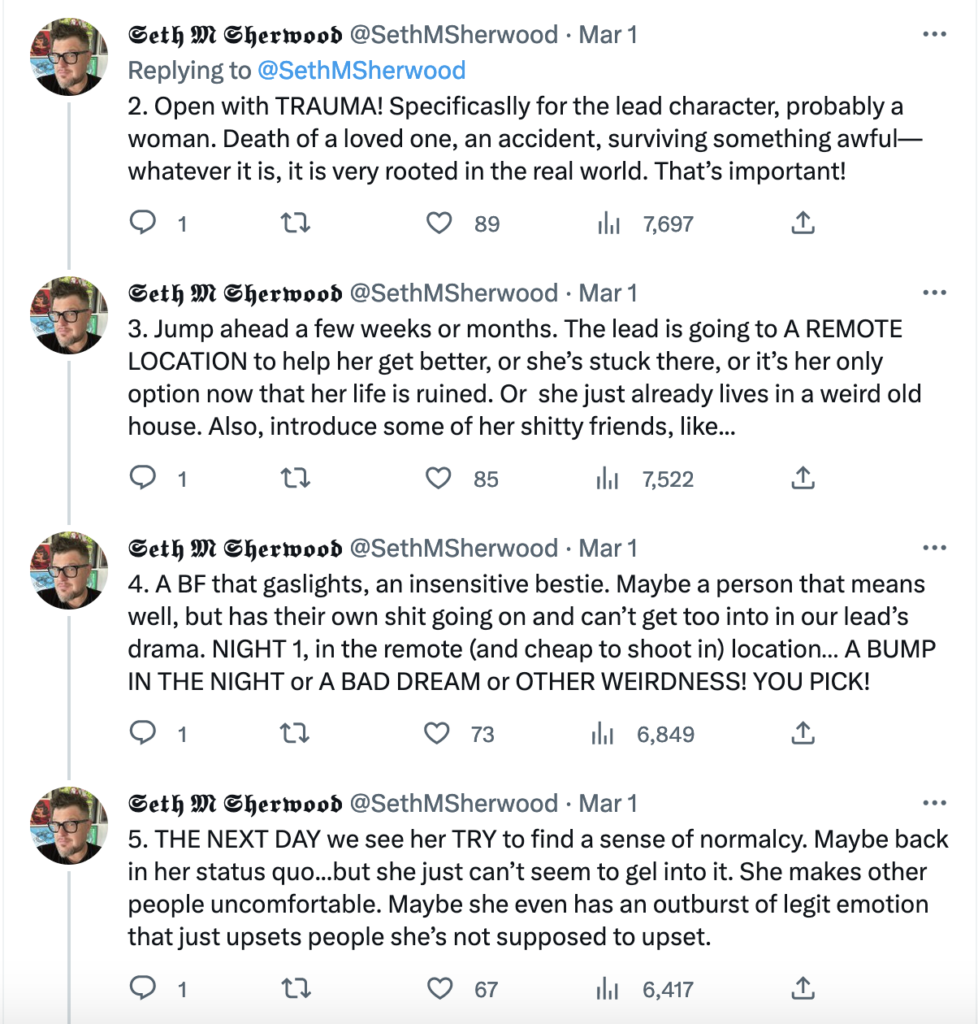

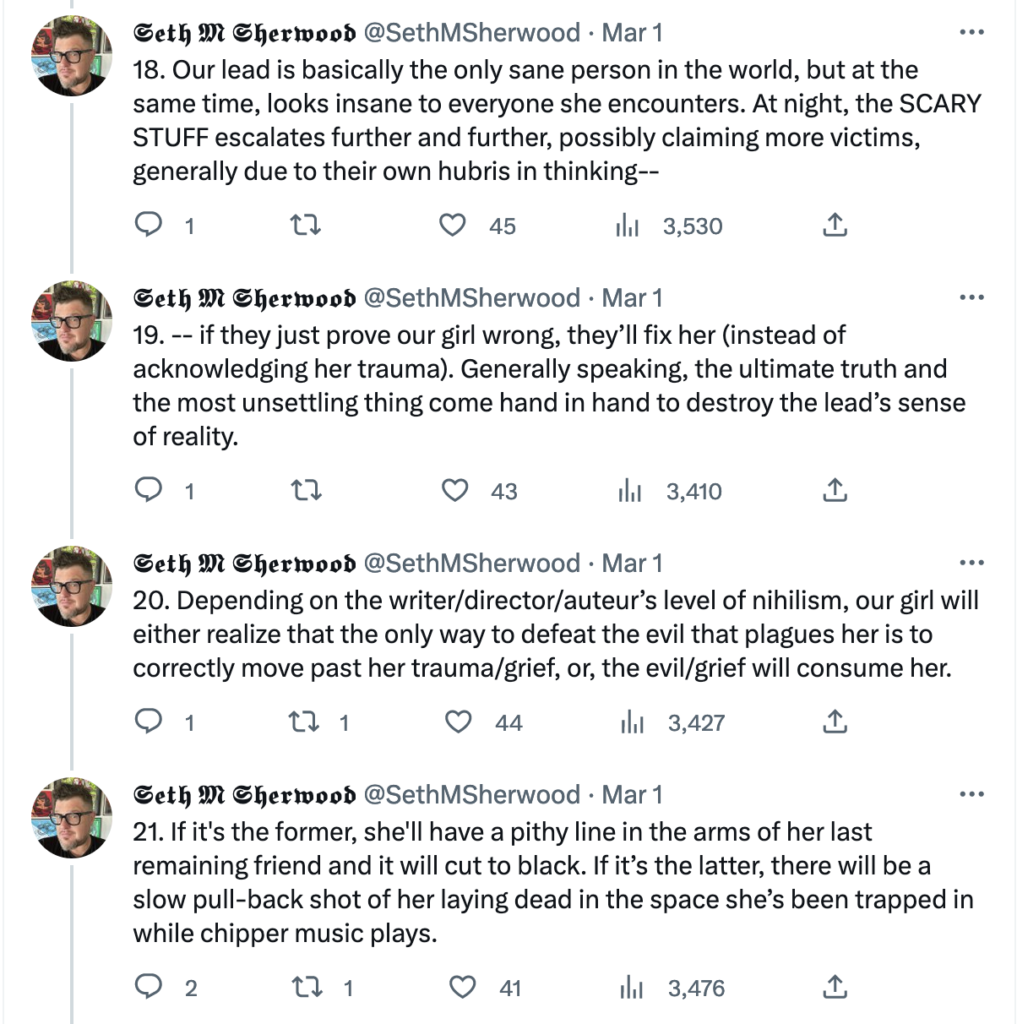

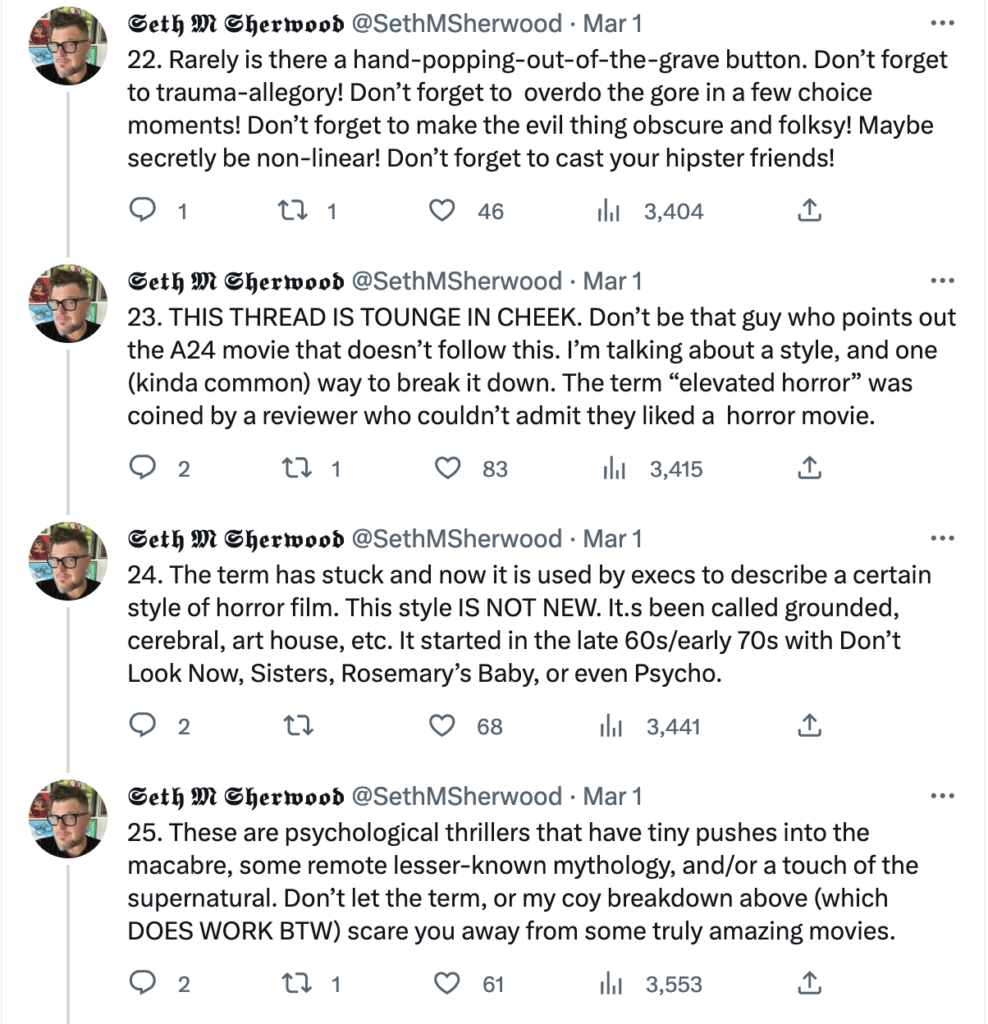

1. HOW TO WRITE “ELEVATED HORROR! A thread in which I tell you exactly how to harness your PTSD and A24 the shit out of your script to the point you may actually be able to use your FSA health insurance fund to pay for it cause it’s basically therapy!

— 𝕾𝖊𝖙𝖍 𝕸 𝕾𝖍𝖊𝖗𝖜𝖔𝖔𝖉 (@SethMSherwood) March 1, 2023

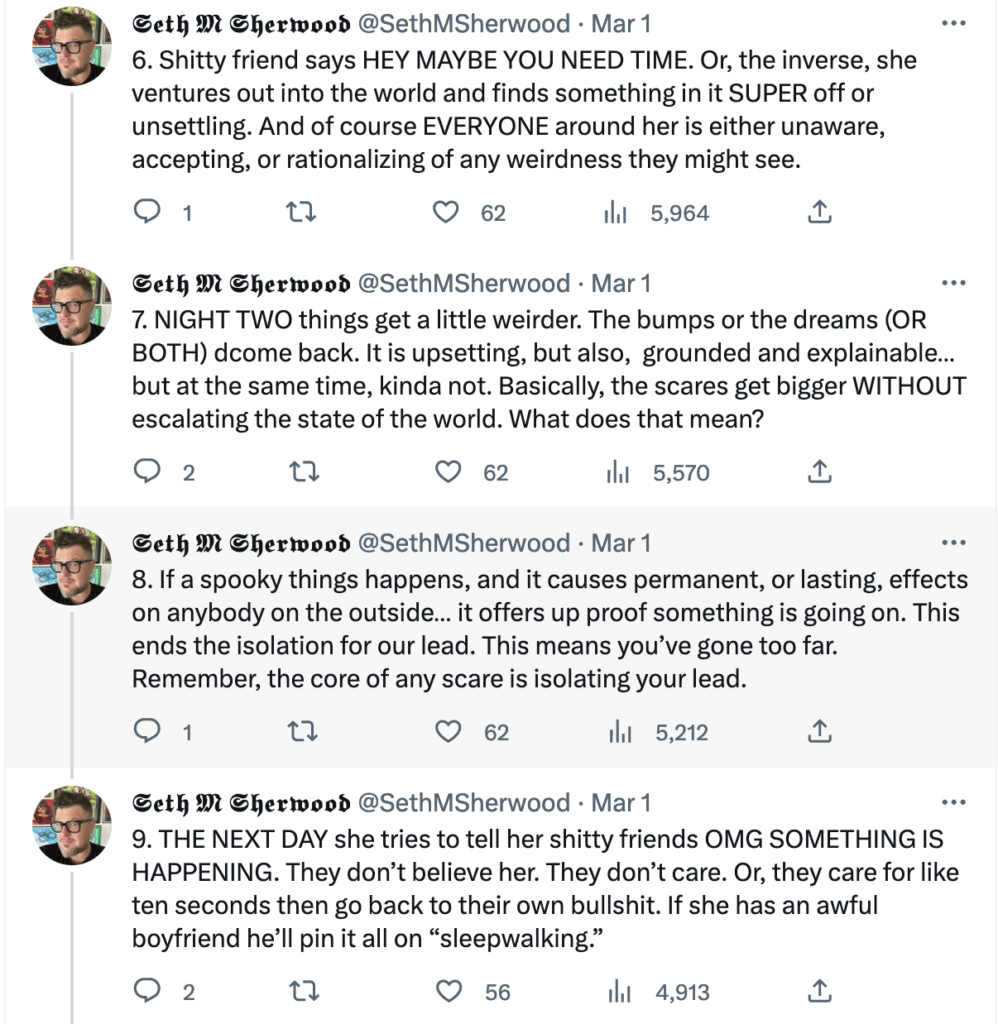

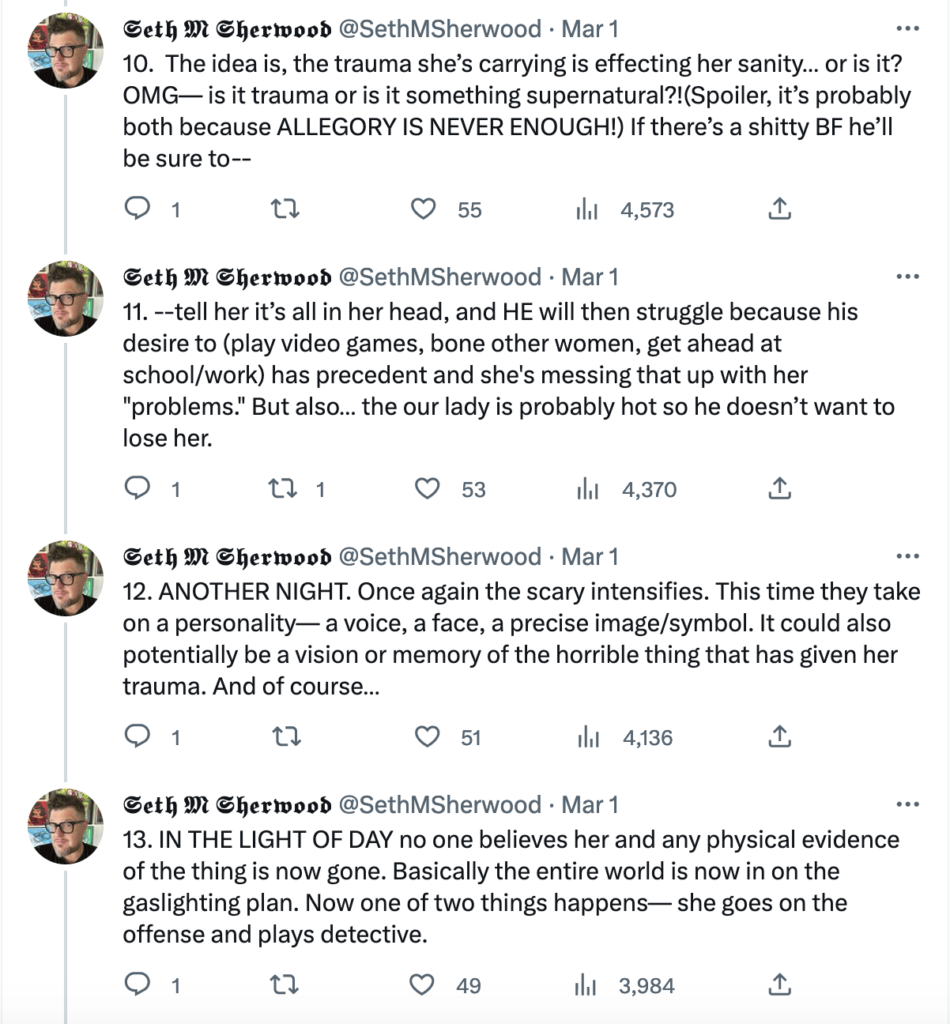

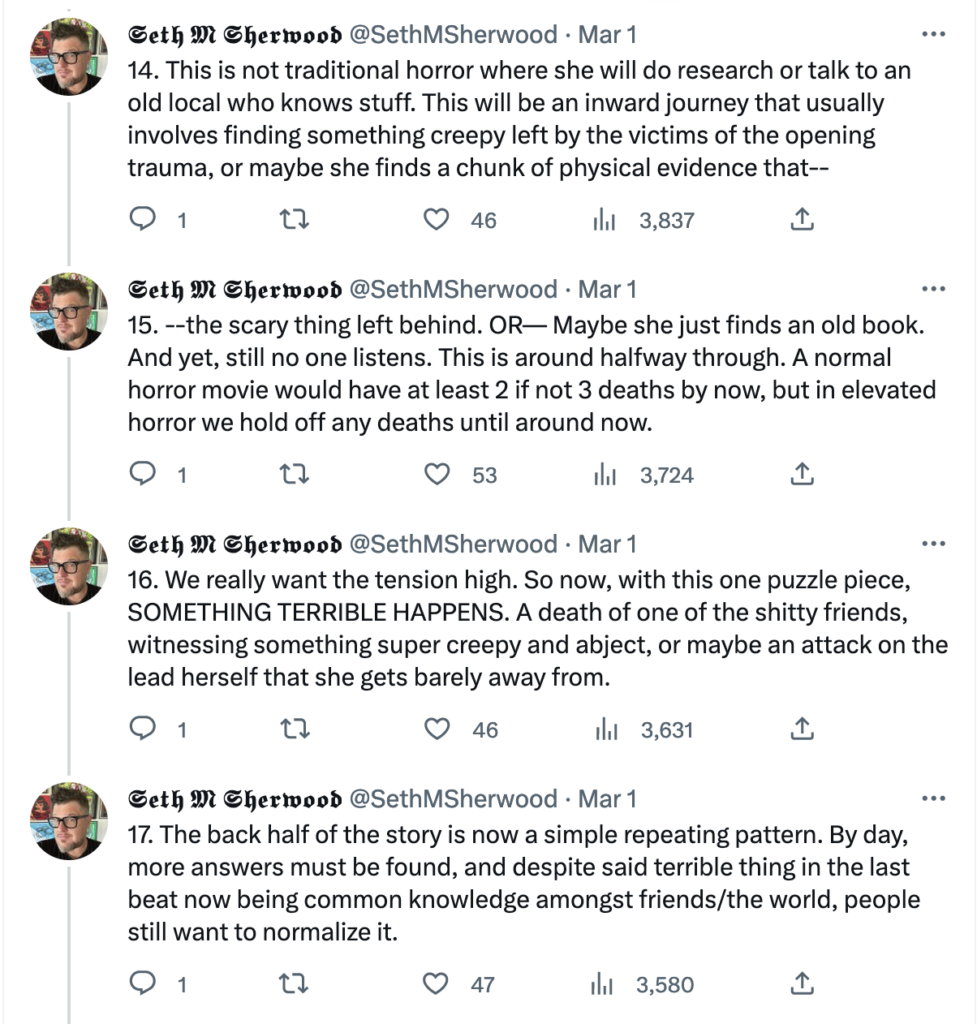

The reason I found this thread so interesting is because Sherwood is making the point of how cliched every script he reads in this genre is by highlighting the absurdly common beats that he sees over and over again. Don’t get me started on how often I encounter the gaslighting boyfriend. At this point, you might as well just make “And the Gaslighting Boyfriend” the subtitle to every horror script that hits the market.

But this isn’t just about horror. Sherwood’s analysis can be extrapolated to represent every genre. Because every genre has its own formula that could be skewered in a similar way. If there’s anyone who knows this, it’s me. Cause I read these violating scripts all day long.

Because of this, I started getting a weird feeling while reading Sherwood’s thread. It was a feeling of, “Is writing a good story even possible anymore?” Because it’s all been done already. So why even try? What are you bringing to the table that hasn’t already been done to death? Aren’t you just matching these same story beats over and over again in your script?

Think about that for a second. Really think about it. Why do you write screenplays? I believe most writers write them because they want to show the world their unique vision, their unique ideas, their individual creativity. And then they want to be celebrated for that. But if your scripts are following the exact same formula that Sherwood lays out, aren’t you just copying what someone else has already done?

I grapple with this question nearly every day. Cause I still want to write stories in some form or another. But if I’m not bringing anything new to the table, then I don’t see any point in pursuing that endeavor.

For example, I love Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. I think it’s the perfect movie. So let’s say I write a high school script about some teens breaking the rules. Is there any chance in my movie being better than Ferris Bueller? No. Not in a million years. So what am I doing here? Trying to write the bad version of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off?

Getting back to Sherwood’s thread, something surprising happened in the comments. A writer pointed out, “That’s the exact formula for The Night House and that movie was awesome.” To which, Sherwood agreed. Then someone else said, “That’s the exact plot for The Howling.” Sherwood acknowledged he was right.

Other movies that he acknowledged following this formula were Midsommar, The Witch, Hereditary, Smile. All movies that got either really high critical marks or did well at the box office.

And even though I learn this lesson once every two months, I always have to learn it again. While, yes, formula can hurt you, it can also allow your script to thrive if the execution is strong.

Now, that’s a vague term: “Strong.” It doesn’t really mean anything without context. So let me give you an example. Every horror script starts with a cold open. Something usually freaky and mysterious happens in the first scene. Well, how you EXECUTE that cold open can range from boring and uninspired to exciting and original.

I read an amateur horror script a while back that had a girl hanging out in her house – her parents were away for the night. The doorbell rings. She goes to the door. She checks outside. There’s no one there. She shrugs, goes back to the living room, plays on her computer for another 30 seconds, and then we see a shadow shoot across behind her. She turns around, peers into the darkness of the hallway. Can’t make anything out. She turns forward and, standing in front of her, is a freak in a mask who then kills her.

Contrast this with the opening of It Follows, where we see this barely dressed girl run out of her house at dawn, continuing to look behind her as if something is chasing her. We can’t see anything though. Her fear is palpable as we try to piece together why she’s acting so strange. She’s so scared that she gets in a car and drives as far away as she can. She hides out on a beach, looking off in every direction, before we cut to the next morning where she’s dead and looks like someone stuffed her inside a trash compactor.

Both of these scenes are following the formula of a cold open. But one gives you the “seen it a million times before” version that doesn’t try to elevate the scenario. The other gives something thoughtful and original that makes you want to keep reading in order to get answers on what happened.

You have this exact choice – lazy and uninspired versus unique and exciting – 15-20 times throughout your screenplay. You have that choice in the way you introduce your protagonist. You have that choice with how you handle your inciting incident. If you’re writing a haunted house movie, you have that choice the first time your characters enter the haunted house.

How are you going to innovate and make these common moments feel fresh?

In addition to this, you have to create a protagonist who we both relate to (we’re sympathetic to their situation because it’s similar to something that’s happened to us) and who we believe. The character must act in a manner that is consistent with real life and, therefore, feels like a real person. As opposed to a character who just acts however the writer wants them to act in the moment, even if by doing so they constantly betray the original character that was introduced.

This is why The Night House worked so well. You believed Rebecca Hall’s character. For those who haven’t seen the film, Hall plays a grieving widower who is cleaning out the lake house that her and her dead husband used to stay at. She then starts seeing things that indicate he’s haunting the place. Rebecca Hall’s part of the mourning widow was written so authentically that we were pulled into her grief.

To expand on that. You’ve gone on a million dinner dates, right? There are no surprises when you go to dinner with someone. And it has acts, just like a script. You’re going to get the menu. Your’e going to choose something to eat. You’re going to chat and eat. You’re going to get dessert. You’re going to hopefully get her to pay the bill and then leave. However, if the person you’re with is engaging and fun and you guys are vibing, that dinner date that you’ve had a million times before all of a sudden feels fresh and new, because you like the company.

We care so much that Rebecca Hall’s character is going to come out of this okay that experiencing this with her is the equivalent of great company on a date.

So, the next time you write a script and you worry, like me, that you’re rehashing a formula that’s been used to death, and, therefore, are unconvinced you can give the reader a fresh experience, remember the two rules I just laid out above.

For every major beat in your story, try to come up with something a little (or a lot) fresher/original than what’s usually used in that scenario. And then give us a relatable genuine hero who we’re really rooting for. Those two things will help you supersede the limitations of formula which will result in a great script even if it’s, technically, similar to every other movie in that genre.