Genre: Adventure

Premise: An archeologist who moonlights as an adventurer goes on a quest to find one of the most important religious relics in history, the Ark of the Covenant.

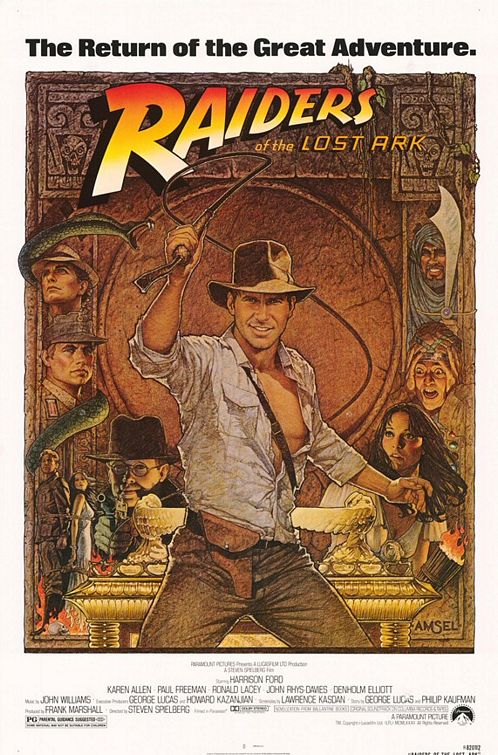

About: This is the first draft of Raiders of the Lost Ark, written by a young Lawrence Kasdan. Kasdan wrote the draft off of 100 pages of notes from Spielberg and Lucas. Every studio in Hollywood passed on Raiders, thinking it too over-the-top. Finally, Paramount stepped in to finance. Kasdan would write four more drafts before production.

Writer: Lawrence Kasdan

Details: 144 pages! (June 15, 1978 draft)

A great exercise for any screenwriter is to read early drafts of movies they love. One of the toughest things for beginners to understand is how much cutting is done from draft to draft. When you start out in writing, you want to include EVERYTHING because you want to show the world just how big and amazing your imagination is. But great screenplays trim every snippet that isn’t necessary. That’s why they read so well (and play well) – because there’s never a dull moment.

I was particularly eager to read this first draft of Indy, a film many consider to be perfect. Was that there in the first draft? Or did it start off as a total stinking mess? Because the first draft of another 80s favorite, Back to the Future, was all over the place. I actually have no idea how they got that to where they did. But the difference here is that Spielberg and Lucas gave Kasdan 100 pages of notes. They outlined this screenplay to the T (yay, more outlining debate in the comments!) before a word was written. Let’s see how it paid off.

For those who don’t know Raiders of the Lost Ark well, there’s this guy, Indiana Jones, an archeologist/adventurer, who specializes in getting hard to find items. He’s told that Hitler is trying to find a supposedly mystical object called The Ark of the Covenant. The army wants Jones to find it before the Nazis do. Indiana must find a series of items first that’ll help tell him where the Ark is, a job complicated by the fact that the Nazis have the exact same information he does.

I learned quite a bit here. You can see the differences from the very start. Do you remember when Indiana is walking up to the cave with the guides? Remember how it was all about looks? About glances being exchanged? About the tension in the air? That’s the way you want a scene to play.

But in the first draft, the characters are exchanging on-the-nose dialogue about the cave they’re going into and the plane that’s going to be waiting for them afterwards. It’s not a ton of dialogue, but the difference in tone is striking. Watching a character assess the situation in a quiet and composed manner creates so much more tension than two characters exchanging even the most sparse lines of exposition.

The next thing I noticed was there was no Belloq (the villain) waiting outside the cave for Indy. Belloq didn’t come into the story until much later, and he was only around sporadically. It was clear that none of the three writers knew their villain yet (there was actually another separate villain who was later eliminated or merged into Belloq).

This happens a lot in first drafts. You’re so focused on the heroes of your story, you don’t give the villain enough thought. It’s only in later drafts that you start fleshing the villain out. This may be why there are so few good villains in screenplays. They’re only getting half the attention of their hero counterparts.

One of the more telling first draft moments was after Indy’s approached by the army agents who tell him he needs to go get the Ark. Kasden included ANOTHER SCENE where Indy is woken up at home by the same agents, who remind him how important this mission is and how they really think he should do it.

This is something every writer does. We tend to believe we need to convince the reader more than we do. “Hmm,” we think, “Will the audience really think that Indy would go on this mission after only one scene?” So we write another. And sometimes another. But these scenes are almost always redundant. It’s the same thing and therefore not needed. This is why they got rid of the scene and just sent Indy off on his mission right away.

The next scene had Indy going to a museum in Shanghai to find part of The Staff of Ra. Once there he must defeat a group of samurais. This scene felt uninspired and unnecessary, which is likely why they cut it. But it’s yet another lesson in writing. Just because you can write a set-piece scene doesn’t mean you should. Technically, you can create a set-piece out of any scenario. A man who wants to brush his teeth encounters a dozen assassins in front of his bathroom. Does that mean you should write it?

Set-pieces have a diminishing-returns effect. The more you include, the less special they become. So you only want to include the a) best ones and b) most necessary ones. Otherwise you’re just creating action where there shouldn’t be any, and the audience/reader is stuck wondering why they’re so bored.

So they cut this scene in the final draft and just took us straight to Nepal, where Marion, Indy’s ex-girlfriend, was. Marion is another interesting aspect of this draft. It’s clear, once again, that the three writers hadn’t thought enough about her character. This is an especially huge problem with male writers writing female leads. They just don’t give them as much thought, and it shows.

Here, there are way fewer scenes between Indy and Marion, and as a result, we never really felt any chemistry between them. With the exception of their first scene in the bar, which they obviously thought a lot about, the rest of the script was more about the plot. And when you’re writing a plot-centric idea like this (find the Ark), it’s easy for your character stuff to get lost. But yeah, after we believe Marion has been killed, she disappears from the screenplay for about 30 pages.

Remember the famous scene in Raiders where Marion and Belloq drink in the tent together? Well that wasn’t here, because neither character had been thought through. This is what rewrites do for you. They allow you to explore areas you neglected previously. And what you’ll often find, is that by improving one neglected area, you’ll improve another. It was probably after someone said, “You know what? Marion isn’t in the script enough. We haven’t seen her for 25 pages. We need something with her.”

So they said, “Hmm, maybe we can create a scene with her and Belloq.” This scene may have then allowed the writers to know Belloq better, which in turn encouraged them to get him in earlier and earlier as each draft went by. To the point where, in the final film, Belloq appears in the very first scene. The scene also exposed how cunning and clever Marion was, which made her more fun to write, which in turn encouraged them to write a few more scenes with her and Indy.

Amongst all this unneeded fat, there was one scene I wish they hadn’t cut. In the scene where Marion is smuggled around the city in a basket while Indy tries to find her, this was originally a chase through the city ON CAMELS. It had this really humorous aspect to it, with Indy awkwardly trying to figure out how to ride a camel as he chased away, navigating low overhangs and uncomfortable humps. It could’ve been really funny.

The funny thing is, that where Raiders Draft 1 encounters its worst stretch is where EVERY 1st draft encounters its worst stretch, which is its second act black hole. It just goes on and on and on, to the point where we’re not sure what’s going on anymore.

I don’t think it’s til page 90 that Indy and Marion get stuck in the pit of snakes. 90 minutes in! It’s because too many of the previous scenes were people talking about where things were and where they needed to look next, and why they needed to look there next. All that was pared down for the final version. We rarely need as much explanation as you think we do. Make it clear what your character is looking for (The Staff of Ra) and let them loose. We shouldn’t need 7 dialogue scenes discussing where that Staff might be. Action over discussion.

The final change was that the climax did not occur with the Nazis opening the Ark of the Covenant. Instead, we get a coal cart chase on rails, much like the one in the second Indiana Jones movie.

This was a perfect example of the writers putting action over story. They’re thinking, “The audience is going to want a great big chase at the end!” They forgot that the story was about getting the Ark. So obviously, in the end, we’re going to want to see what’s in the Ark! That alone will be able to carry a climax, sans a big chase scene, which they eventually figured out.

The first draft of Raiders reinforced to me how much bloat we subconsciously add to our scripts. Keep your eyes on the prize when you’re writing. Make sure your characters are always focused and pushing towards their next goal. If you get stuck in no-man’s land (a lack of clarity in what your characters are doing), you can easily lose an audience.

The bloat kept this from being an “impressive.” But the guts of a great film were still there.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Use the uniqueness of your environment to create the sequences that drive your story. Every environment is DIFFERENT. You need to then utilize the differences of that environment to make your script different. In other words, a break-up should play differently depending on if it’s in an airport (a couple breaks up while they’re going through security), in a grocery store (the couple destroys a fruit stand while breaking up), or in a a cappella group (the couple breaks up with each other a cappella). When I saw a camel chase in Cairo I thought: “Perfect!” That’s the exact kind of chase that could only happen in this movie in this moment.