A month ago, I was in the middle of reading a script and I was bored out of my mind. Whenever I’m bored, I instinctually check what page I’m on. So I looked up at the top of the screen and noted that I was on page: Four. That’s right, page four. How bad does a script have to be for the reader to already be bored by page four? Bad. And yet, this is common. Especially with amateur screenplays.

It occurred to me as this was happening that all screenwriting is is time-buying. You’re trying to buy more time with the reader. If you can promise them that that next page is going to be just as entertaining as this one, they will keep turning the pages. And nowhere is this more important than the first ten pages. Because the first ten are where you hook someone. If you can pull them in immediately and not let go, it acts as a promise – a promise to the reader that “I’m going to entertain you.” Once that trust is established, you have them.

This got me wondering: What if I threatened every writer that THE SECOND I was bored, I would stop reading their script? In other words, if I was bored at the end of the first page, I wouldn’t keep reading. If I was bored at the end of the first paragraph, I wouldn’t keep reading. If I was bored AT THE END OF THE FIRST SENTENCE, I wouldn’t keep reading. Would writers change the way they wrote their first ten pages? Of course they would. Every sentence they wrote, they would ask, “Will this keep the reader reading?” And I suspect that everybody using this strategy would become a markedly better writer in the process.

Now some of you are probably thinking, “This is unrealistic, Carson.” All it would do is result in a bunch of scripts catering to the ADD crowd. The literary equivalent of Michael Bay lining up a series of explosions. But here’s the thing – keeping someone entertained doesn’t mean dropping the reader into a firefight or an argument. It can mean that. But there’s more than one way to lead a horse to water.

Yesterday’s script is a perfect example. Promising Young Woman starts with a group of men leering at a hot drunken woman in a bar. Right away, we know something very bad has the potential of happening. So guess what? We keep reading to find out if it does. It’s a very simple dramatic storytelling device. And it’s ensured we will at least read until the end of this scene. No ADD-catering required.

Contrast this with the opening of Monday’s script. We’re in the aftermath of a giant accident and our hero’s daughter has died. The scene creates a little bit of mystery (“What caused this?”), which creates just enough momentum for me to begrudgingly read on. But as an opening scene, it’s weak. Nothing is happening. There’s no tension. There’s no suspense. There’s no conflict. All of that happened before the scene. All sorts of alarms go off when I see this. If there isn’t a single well-developed story skill in the opening scene, why would I think this writer had the skills to entertain me for the next 100 pages? And guess what? I was right. There were no storytelling skills on display for the rest of the script. The script was boring.

But let’s get back to my idea. What if you knew that the reader would stop reading your script the second they were bored? Would you become a better writer in those first ten pages? Would you focus more on entertaining the reader? I say you would. One of the best examples of this is a script that sold all the way back in 1994. It was the hottest spec of the year. Everyone was talking about it. And it went on to become a hit movie. Here’s the first page of that script…

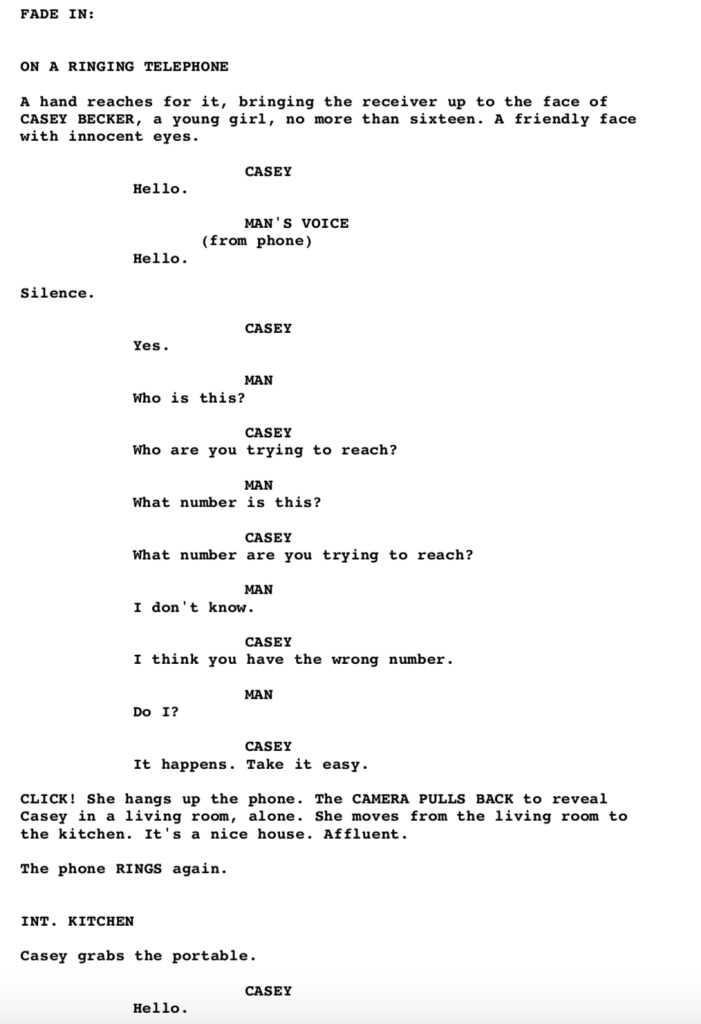

Is there anyone here who can honestly say, “I was bored, I stopped reading?” A show of hands. That’s right. Not a single hand raised. This first page, from the script for “Scream,” is the embodiment of my philosophy. The script grabs you from the very first sentence, and there’s never a point after that where you can stop reading.

“ON A RINGING TELEPHONE.” Well duh, we have to find out who’s calling. Establish a 16 year old girl. “Innocent eyes.” Why point out she’s innocent? Might she be in danger in the coming lines? “Hello.” “Hello.” Silence. Bam, this conversation is already interesting. The person calling isn’t following normal protocol for a phone call (“Hi, is Jake home?”). They just say, “Hello.” Then silence. “Yes,” she asks. “Who is this?” he replies. Okay, now you really have me. The person who’s calling doesn’t get to say, “Who is this?” That’s the answerer’s duty. What’s going on here? I have to read more.

The conversation continues with the man asking questions he shouldn’t be asking. “What number is this?” Then answering her questions in a creepy way. “What number are you trying to reach?” “I don’t know.” “I think you have the wrong number.” “Do I?” Casey, trying to act above it, hangs up on him. “The phone RINGS again.” Casey answers the phone again. “Hello.” HOW CAN YOU NOT TURN THE PAGE after this? How can you not want to find out what happens next? This is how you write to keep the reader’s attention.

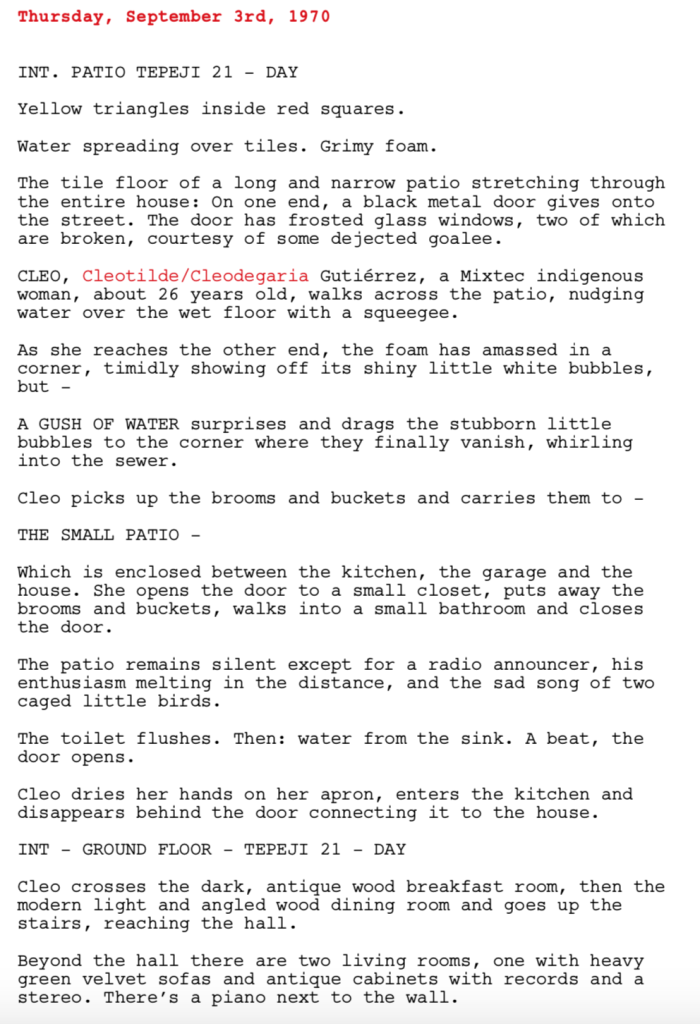

I know. I can already hear you zipping around the internet looking for examples of movies that start slowly. “Roma doesn’t start fast, Carson! Roma was nominated for an Academy Award!”

Come on, you’re smarter than this. Roma isn’t a spec script that needed to win over readers. If you are a writer-director, if your movie’s development is already paid for, if your movie is being fast-tracked, if you’re adapting a book, you do not need to worry about this problem. The irony is that all of these writers would do well to still abide by this philosophy. But they don’t, which is partially why so many of these movies are boring. Don’t forget your unique circumstance. You are a nobody whose only influence on someone is the words you write in this document. You’d be smart to use every one of those words wisely. Hook them and never let them go.

Okay, Carson, you’ve made great points as always. But how do we actually execute this plan? What’s the trick to writing an amazing first ten pages? Unfortunately, there’s no trick. But there are certain setups that work better than others. One of the best things you can do is identify all your favorite movie openings – movies that hooked you right away – Then ask, “How did they do that?”

One thing that we’ve identified that works is to place someone who’s helpless in harm’s way. That worked for us in Promising Young Woman. And it worked in Scream. It doesn’t have to be a woman. It can be a kid. Or, if you create a situation whereby a grown man is helpless in a situation, that might work as well.

Another theme of good early scenes is that we’re dropped into something important happening. We’re not dropped in afterwards (like Absence of Courage). We’re not dropped in five hours before (characters going about their everyday lives). We sense right away that something important is happening and therefore we want to find out what happens next. For example, if you opened on a woman in a boardroom sweating bullets, trying to act like she’s not sweating bullets, and we pull back to see she’s in an intense job interview, getting hammered with hard question after hard question, that could hook a reader.

Conversely, you can hook us in the build-up TO that interview. You could place that same job applicant in the waiting area, sweating bullets, going over her notes, trying to remember everything, eyeing the other applicants sitting nearby, all of whom are better looking and better dressed. If I’m dropped into that moment, I’m going to want to keep reading to see how that woman performs.

You could take that same character, however, and start with her waiting outside school to pick her daughter up, and you’ve lost us. It’s not the most boring thing you could start on. But there’s no importance attached to it. Where’s the suspense? Where’s the “reason to keep reading?”

Then again, with a little finagling, you could turn this scene into an interesting one. Focus on the woman waiting while all the other children come out and meet their parents. And with each passing kid that isn’t hers, there’s a looming sense of dread in our protagonist. She’s craning her neck. Looking at a few groups of girls chatting. Her daughter has to be around here somewhere. All of a sudden, a teacher approaches, a concerned look on her face. “Maggie?” she says to our protagonist. “What are you doing here?” “What do you mean? Where’s Tracy?” “You don’t remember? You called an hour ago. To say her uncle was picking her up.” We can see from Maggie’s eyes that she did not call an hour ago to say Tracy’s uncle was picking her up. And now we have to keep reading.

The real trick here is creating an interesting situation. Don’t plop us into some boring mundane scene. Come up with something that’s got some stakes attached to it. Someone’s in danger. Something’s gone wrong. There’s conflict involved. There’s mystery. Give us something that’s impossible to stop reading. And when you finish that first scene and you still have five pages left in your first 10, don’t rest on your laurels. Give us another scene we can’t stop reading. Hold yourself to the same standards you hold other writers to. You’re bored out of your mind reading other writers’ work. Well, then don’t do the same things they do.

So here’s how this is going to work. We’re having a First 10 Pages Contest. The one rule of this contest is that THE SECOND I’M BORED, I WILL STOP READING YOUR PAGES. If I’m bored in the first paragraph, I will stop reading. I have no problem giving up on your pages 20 seconds into them. Knowing this, will you become a better writer? That’s the experiment here.

I don’t know what the prize will be other than featuring the winners on the site. But I can tell you this. I’m not going to feature bad work. If not a single entry results in me reading the full ten pages, there will be no winner. I’m genuinely curious to see if anybody get can me to read the full ten. Because 99% of the time, I wouldn’t read past the first scene if I didn’t have to. I want you to really internalize that. Writing a screenplay isn’t this giant complicated process of navigating readers and agents and staying updated with trends and blah blah blah. It’s writing a series of words that make the person reading it want to keep reading. If you do that, you will be successful.

Submissions will be due a month from now on Sunday, February 10th, 11:59pm Pacific Time. Send a PDF of those pages to carsonreeves3@gmail.com with the subject line: FIRST TEN PAGES. No logline or synopsis needed. You can include a title page if you want. Up to you. You can send them starting today.

Let’s see who can pull this off. Oh, and one last reminder…

MAKE IT IMPOSSIBLE FOR ME TO STOP READING