How a screenwriting fatal flaw is silently killing all the latest Marvel movies.

Ant-Man crept over 100 million dollars for the 3-Day weekend (104 mil), saving a little bit of face, but not much (Black Panther 2 opened to 181 mil, Thor Love and Thunder to 144, Doctor Strange 2 to 187, and Spider-Man No Way Home to 260).

I was fully intending on seeing this movie. I love Ant-Man. I like Paul Rudd. I thought the first movie was clever and gave us something new. The character of Ant-Man himself is fun. His powers are weird in cool ways (he’s Ant-Man but he can turn giant??).

But leading up to this movie, I couldn’t escape all the bad buzz surrounding the film. I kept hearing troubling things about the storytelling. That it wasn’t really about Ant-Man. It was about his family. It was about Kang. They even made way for introducing one of the strangest characters in the Marvel Universe – something called “Modoc.”

I have a question. Why are you making movies that don’t prioritize your main characters, Marvel? The answer to that question is both a window and a mirror. It’s a window into the mind of Kevin Feige, the head of Marvel, and a reflection of the franchise’s current priorities.

The movies are no longer about the main characters. They’re about everything surrounding those characters, as well as what’s going to happen NEXT, in future Marvel movies and TV shows. You came to this movie to be entertained now? F U. You have to see the next three Marvel movies if you want to be satisfied.

Marvel may think this strategy is a winning one. But I’ve paid to see nearly every Marvel movie in theaters. The only two I didn’t were Thor 2 and Eternals.

So it says a lot that, despite being a character I enjoy, that this movie wasn’t worth my time. And if I – someone whose entire life exists around movies – wasn’t interested, you can bet your bottom dollar that a lot of casual moviegoers are feeling the same.

Four of the last five Disney-Marvel movies have received an RT score of under 75%. Two of those (Ant-Man 3 and Eternals) were under 50%. Contrast that with the five before that, none of which were lower than 75%. Clearly, the quality of these movies is dropping. And it doesn’t look like it’s going to get better. The Marvels (the Captain Marvel sequel) just got pushed back six months with rumors swirling that it’s unwatchable.

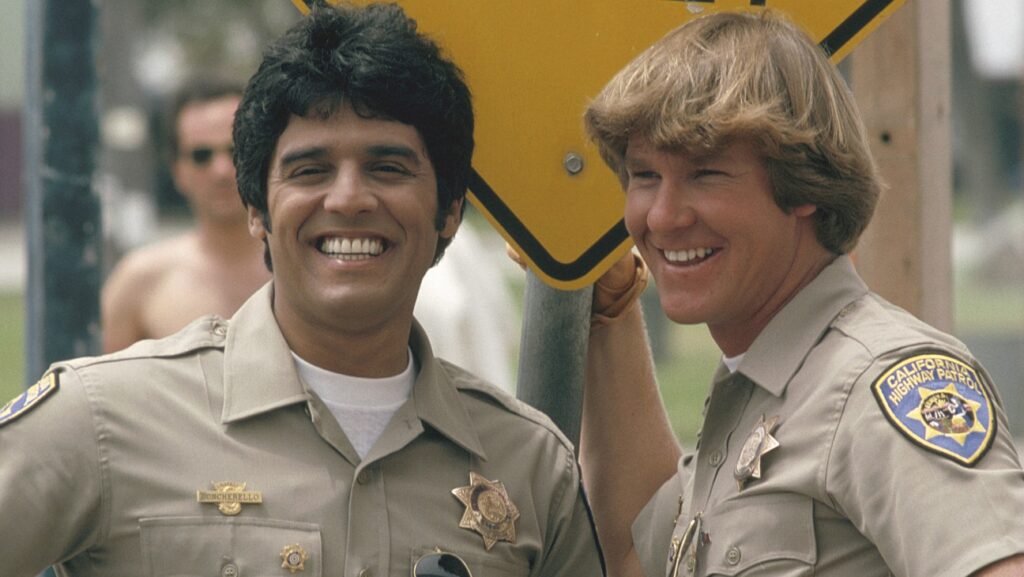

Why does this matter? Because Marvel is the movie business right now. It’s holding up the entire tent. If it crumbles, there goes the circus. And the way this relates back to Scriptshadow is that Marvel has embedded a screenwriting fatal flaw into all of its latest movies. For whatever reason, they are unaware of this blind spot. And if they don’t turn their head and see the car in the other lane soon, they’re headed for one of those Chips-level pile-ups.

Yes, I just referenced Chips. It’s Monday. Anything can happen.

So what is this flaw?

The best screenplays are simple stories told well. Clean narratives. Clear goals. Clear motivations. A limited number of characters so that the script has time to imbue those characters with adequate flaws that can be explored and resolved. It’s no accident that the best comic book movie of the last five years – Joker – used this template to a T.

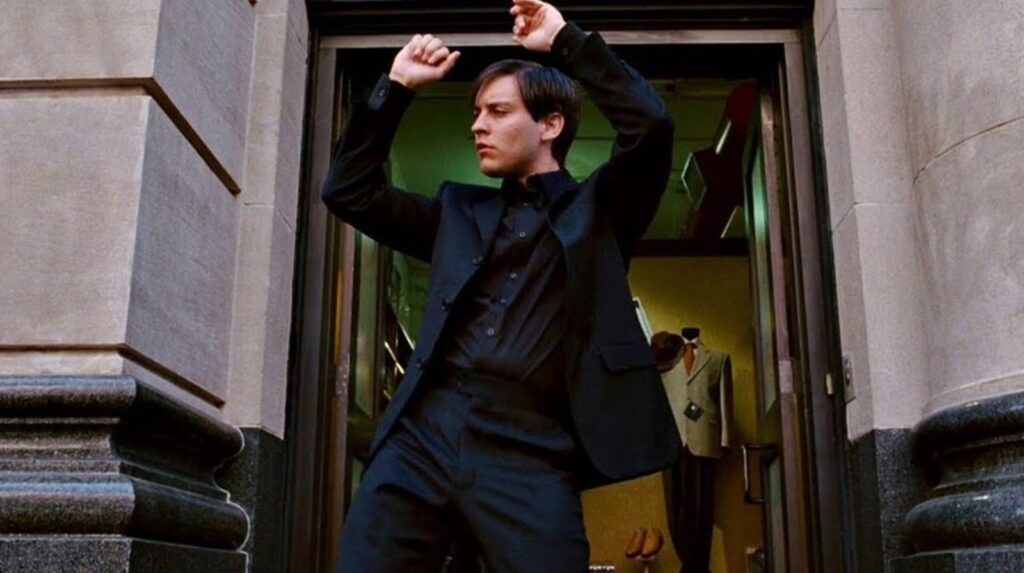

Do you guys remember the first Spider-Man franchise with Toby McGuire? The first film was good. The second film was even better. And the third film was trash. Do you remember why that film was trash? Because they famously tried to do too much. Too many villains. Too experimental (I think at one point there was a musical number). Narrative was all over the place. That movie was the epitome of what happens when you try to overstuff a screenplay.

I guess that movie has now been memory-holed at Marvel. I don’t think they’re aware it exists. Because the original Spider-Man 3 has, inexcusably, become the template Marvel now uses to write their movies.

But Carson, what about Spider-Man No Way Home? That had a bunch of characters in it and it worked. True. I’m not saying the strategy can’t work. I’m just saying it’s way harder to make work. So, if you’re going to use it, you need to take the extra time required to get the script right.

This is not rocket science. If you have ten storylines in your screenplay instead of two, you will need more time to write those storylines! This is exactly what James Gunn has been saying as he ramps up DC Studios. We’re going to take that extra time and get the scripts right. The Flash looks really good even though it has a lot of stuff going on. Not coincidentally, I’ve heard that they worked crazy hard on that screenplay.

Dr. Strangelove 2 was awful. Thor Love and Bananas was awful. Ant-Man Quantum-shame-on-ya looks awful. No offense, Kevin Feige, but get your sh— together, man. What are you doing?? You’re cranking out garbage and, in doing so, you’re damaging your brand. Every Ant-Man 3 you put out makes us less confident in the next Marvel movie.

The simple truth may be that Marvel doesn’t have any stories left to tell. There have been 30 of them. Star Wars couldn’t even come up with 6 good movies. Marvel is telling three times that many and reached the point where, maybe, it can’t tell simple stories anymore. The audience wants something new, wants something different. But what if there’s nothing different left?

When you don’t have a good story to tell, you rely on gimmicks. For the regular screenwriter, gimmicks are things like writing your screenplay in the first person, or throwing a couple of forced twists in the middle of your story (the main character dies!).

For the Marvel screenwriter, gimmicks are including X-Men and Fantastic Four characters from other dimensions (Dr. Strangelove 2), or prioritizing a shocking post-credits scene over the movie itself (Eternals). Those sorts of things can be fun. But if they become more important than writing a great movie, that’s when you get into trouble. And it seems like Gimmick writing is the new strategy over at Marvel.

Cameos like this have taken precedence over dramatically compelling plot developments.

Cameos like this have taken precedence over dramatically compelling plot developments.

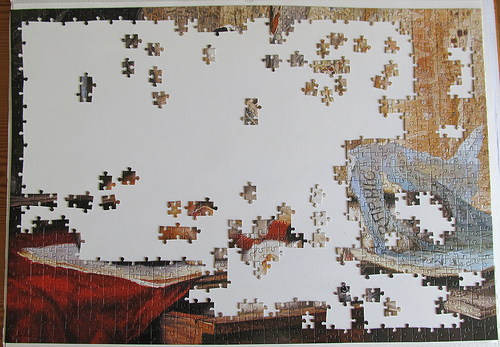

The more I break screenplays and movies down, the more I realize how hard screenwriting actually is. It’s a lot like those sophisticated puzzles you used to do which had 2000 pieces. A puzzle like that takes serious amounts of time. You need to really sit there and sift through the pieces and try combinations to see if they fit, and do that day after day after day.

Then, once you get that outside edge of the puzzle figured out, you could keep filling in and filling in and filling in, until you finally put the whole thing together. Marvel movies feel like they stop working on the puzzle before that middle section is finished. The edge is in place. But the middle is still a murky mess. There are a few clumps of pieces that go together which are vaguely tossed in the middle. But it’s not enough to know what you’re looking at.

Dr. Strangelove 2 was one of the sloppiest big budget movies I’ve ever seen. And it’s because it was such a mess that when I heard even the slightest bit of rumblings about the writing in Ant-Man 3 being weak, I was out. Because I had recent proof that Marvel was getting lazy and making bad movies.

If they want to play this game where launching some dumb character named Ironheart is worth messing up the flow of their entire second act for (Black Panther 2), godspeed to you. Do that. But I’m warning you. Prioritizing the wrong things in storytelling has consequences. You did it in Dr. Strangelove 2. You did it in Black Panther 2. Now the critics are onto you. They’re not giving you breaks anymore, which is why you pulled a sub-50% RT score and the second ever “B” cinemascore for a Marvel movie. The Marvel fanbase is more forgiving. But believe me, they *will* eventually turn on you if you keep this up.

Last month, Call of Judy dominated the competition!

This month, a new logline will rise to the top. And with it, a new legend will be born. Or they’ll get a “wasn’t for me” and we’ll forget about the script a week later. One of the two!

Every second-to-last Friday of the month, I will post the five (or six??) best loglines submitted to me. You, the readers of this site, will then vote for your favorite in the comments section. I then review the script of the logline that received the most votes the following Friday.

If you didn’t enter in time for this month’s showdown, don’t worry! We do this every month. Just get me your logline submission by the second-to-last Thursday (March 23 is the next one) and you’re in the running! All I need is your title, genre, and logline. Send all submissions to carsonreeves3@gmail.com.

Also, this is a reminder that a lot of your are shooting yourselves in the foot with your loglines. You’re making catastrophic mistakes (clunky phrasing, being too vague, overwriting, not adding that ‘must-read’ climax finisher to your logline) that give you no shot at script requests. It genuinely hurts me to see because you may have a good script but nobody’s going to want to read it until you’re able to properly write a logline for it. If you want a logline consult with me, they’re cheap – just $25. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com

Are we ready? Voting ends Sunday night, 11:59pm Pacific Time!

Good luck everybody!

Title: FEAR CITY

Genre: Thriller

Logline: A serial killer has an entire city living in fear – until he is kidnapped by three petty crooks looking to make their big score. The ransom demand they make to City Hall is chillingly simple: “Give us a million dollars or we’ll let him go again”…

Title: Tide Pool

Genre: Thriller

Logline: Two good Samaritans, with their relationship on the brink of collapse, find themselves in a fight for survival while attempting to rescue a juvenile great white shark that has become stranded in a rock pool during low tide.

Title: PROVEN

Genre: Coming-of-age Thriller

Logline: When three, poverty-stricken best friends attempt to strike it rich by retrieving a dead Bigfoot from a remote river, their plan is endangered by a rapidly rising tide and the team of vicious hunters who killed the beast.

Title: Ninestein

Genre: Comedy

Logline: Scientists attempt to clone Albert Einstein to save the earth from an incoming asteroid, but when the process goes awry they are left with nine clones, each just a fraction as smart as the original.

Title: Olympus Park

Genre: Sci-fi

Logline: When a naive businessman unveils a theme park of reincarnated historical figures, he must convince a ruthless FBI agent that his attractions are safe when a clone of Elvis Presley appears violent.

Title: Rosemary

Genre: Horror/Dark Comedy

Logline: A prolific serial killer struggles to suppress her desire to kill during a weekend-long engagement party hosted by her new fiance’s wealthy, obnoxious family.

Submissions for the Logline Showdown need to be turned in tonight, Thursday, February 16th, by 10pm Pacific Time!

FINAL REMINDER that we’ve got the year’s SECOND Logline Showdown coming up this Friday. For those who don’t know what the Logline Showdown is, anyone can send me a logline at carsonreeves3@gmail.com. It must be a logline for a completed script.

I choose the 5 best submissions and place them up here, on the site, for you to vote on, over the weekend. Whichever logline gets the most votes, I review that script the following Friday.

If you want to enter, which is 100% free, here are the instructions:

Send me your title, genre, and logline. Nothing more.

Send it to this e-mail: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

Send it by 10pm Pacific Time, Thursday, February 16th.

Now, on to today’s article!

Tuesday, after writing my review for Male Pattern Baldness, I noticed that something I wrote at the beginning of the review was a criticism I’d been writing a lot lately, in both scripts I reviewed and scripts I’d given notes on.

The observation was: This script started off strong then lost steam.

I’ve been writing that SO MUCH lately so I wanted to write an article exploring why this happens and what you can do to prevent it.

Let’s start with the why. Why does this happen? There are several reasons. But most of it comes down to jumping into a script before you’re ready. We’re all guilty of doing this. We get an idea on Thursday. We get really excited about it over the next 24 hours. Then as soon as work ends on Friday, we start writing like a maniac and bang out as many pages as we can over the weekend.

Those pages, while sloppy, *do* have a lot of energy in them – especially the first few scenes. But then once the high wears off, so does the energy. Each subsequent scene feels like a chore. Which can be demoralizing if you’re only on Scene 14 and, therefore, still have 36 scenes to go.

How do we prevent this from happening? The problem can be broken down into two scenarios.

Scenario 1 is ignorance. A writer doesn’t yet understand how to keep a story interesting from page 1 to page 110. They need to keep learning how to write a screenplay and how to tell a story (two different skills, by the way) in order to fix this issue.

Scenario 2 is laziness. The writer knows how to keep the reader invested. But he also knows that, to do so, it takes a lot of work. It’s hard to come up with a fresh captivating plot that keeps the reader on his toes. And they don’t want to do that work.

This is why you see professional writers write the occasional bad script. They start thinking everything they write is gold because why wouldn’t it be? They’re getting paid a lot of money for their words. So they just don’t do the hard work required to keep the reader captivated.

Most of the people on this site fall into the first category. They don’t yet know how to make their script captivating past that first act. If you’re part of the second category, all I have to say is shame on you. Cause if you know how to do it and you’re not putting in the work to do so? That’s screenwriting malpractice. Get your hands dirty, get in there, and do the necessary planning and rewrites that are going to result in a great read.

All right, now that we’ve brow-beaten the second category, let’s help everyone in the first category. How do you start off with a head of steam and never slow down?

Funny enough, that’s the first tip. You have to embrace the philosophy of grabbing the reader right away and never letting them go. This might sound like obvious advice. But every single day I read a script that doesn’t abide by it. The philosophy I more commonly encounter is, “Grab the reader right away, now I’ve earned the right to slow down, I’ll start making things fun again later.”

You really don’t have the luxury to take this approach in the spec script market. You have to make things move in every single scene. So if you simply embrace that philosophy of grabbing the reader and never letting them go, you’ll be ahead of 90% of your competition.

The next thing you need to get right is generating a concept that actually warrants a full 110 page story. The old industry saying is: “A concept that has legs.” A lot of concepts don’t have legs. And the frustrating thing about these scripts is that you’re trying to make a plane fly that doesn’t have wings.

Now, most writers don’t figure out their script lacks legs until three months into writing it. A question that can help you identify leggy concepts is: are you going to have trouble cutting your script down to 110 pages or are you going to have trouble coming up with enough story to get to 110 pages?

If your situation is the former, your concept has legs. If your situation is the latter, it probably doesn’t.

To give you more specific examples, a movie like “Fall,” which follows two girls who climb to the top of a radio tower and get stuck – that concept was doomed cause it clearly didn’t have legs. “The Whale” is another film that people have complained about for not having legs (literally, since the main character can’t stand up), which is why it’s not getting the acclaim everyone thought it would get.

Even though I didn’t love, “Nope,” that script, with its dying movie-horse ranch business, the family issues between brother and sister, the rival Old West theme park and the flying alien predator, gave Peele plenty of story to work with.

Just to be clear, I’m not saying simple ideas can’t have legs. If you include a robust main plot, plenty of characters, and a fully fleshed out world, you should be okay. But any story that has that juicy fun setup (like Fall) yet you can’t think up more than 5 scenes off the top of your head? Those are the concepts you probably want to avoid.

Next up, you need either a really compelling main character or a really compelling supporting character. The reason you need this is because it doesn’t matter how good you are at plotting or fleshing out your story if your characters are boring. You could be a master plotter and the reader is still bored because you haven’t given us someone we like to watch.

To create this character, you want to start out by either making them likable (Thor) or interesting (Arthur Fleck in Joker). The less likable your hero is, the more interesting they need to be. Cause if they’re not likable and only kind of interesting, we’re not going to root for them.

Then, you want to create a hole in the character’s life – a blind spot, if you will – that needs to be filled in order for them to become happy and whole. A recent example would be Evelyn from Everything Everywhere All at Once. She had given up on her family, convinced that she screwed up by marrying a weak husband and subsequently having a weak daughter.

She needed to fill that hole with love. We stuck around to see if she was going to do that (love her family again). If you do this right, you create the opposite effect of what I just outlined. Which is that, even if you’re not a good storyteller, we will want to keep watching to see if our hero fills their hole and becomes happy again.

You might wonder how character stuff “keeps the story moving.” That’s part of the magic of storytelling. A compelling character shortens time. We can’t get enough of them. So even if the story itself isn’t great, we’re lost in this character’s existence. And when that happens, time moves differently in our heads. We feel like the story is traversing through time faster.

Moving to the more technical side of things, you must know how to keep an engine underneath your story at all times, specifically throughout the second act, which is where most engines run out of gas, and the reader either doesn’t fill them up again or doesn’t introduce a new engine.

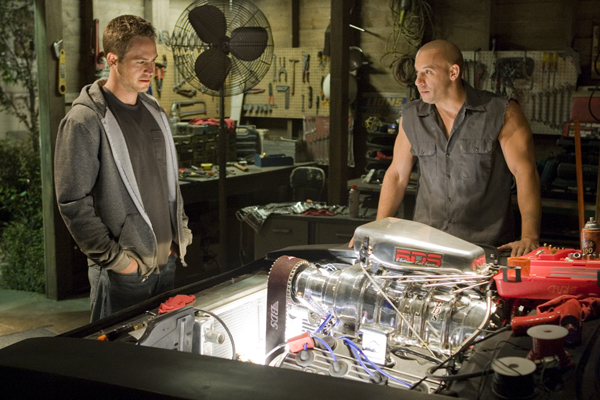

“I just don’t know if this is a big enough engine for our story, Turreto.”

“I just don’t know if this is a big enough engine for our story, Turreto.”

An engine is just goal + stakes. It’s a goal your heroes (or in some cases, the villain) need to achieve and it needs to be very important. In Avengers Infinity War, the goal is in Thanos’s hands. He wants the infinity crystals so he can snap half of the universe out of existence.

But that goal is achieved by the end of the movie. So, going into Avengers Endgame, you need a new engine. The engine switches over to the good guys, who decide to go back in time to get the crystals to reverse Thanos snapping half of the universe out of existence.

The thing to remember is that there always needs to be an engine underneath the story. If there isn’t, or if the engine has low stakes, that’s when your script starts to feel like it’s running out of steam.

If we use Tuesday’s script, Male Pattern Baldness, as an example, we can see just how the absence of a couple of these principles resulted in it losing steam. First, the main character wasn’t really that likable and wasn’t really that interesting. So pretty much before the story gets started, it’s screwed. But let’s be generous and say that maybe some readers related to the hero’s anger and, therefore, rooted for him.

While you do have a goal – he’s trying to get his wife back – I’m not sure the stakes are high enough. Do we really feel like, if he got her back, that he would be happy and everything would be good again? I didn’t. So the stakes weren’t high enough. We have to believe that the character’s goal is EXTREMELY important if we’re going to stay emotionally invested in the story.

All right, let’s summarize here. To make sure you don’t start strong then peter out, first embrace the writing philosophy of: grab them and never let them go. Next, make sure you have a concept that has legs. Next, give us a character we either like or find highly interesting. Give them a hole that they need to fill in order to become happy. Finally, make sure there is always an engine running underneath your story. If an engine completes its mission, introduce a new one.

And finally, understand that the way to make the rest of your script as good as the first few scenes, is through rewrites. You keep rewriting every scene until it’s just as energetic or dramatic or suspenseful or captivating or shocking as the first few scenes. If you take even one scene off, I promise you the reader will notice it. So do that extra work until all of your scenes are so good, the reader has no choice but to keep reading.

That way, I won’t have to write this annoying phrase – “I love how the script started but it ultimately ran out of steam.” – ever again. :)

Genre: Comedy

Premise: A mystery about what paper jams can teach us about life. After an inexperienced detective starts investigating a death at the Paper Jam department of a major corporation on the verge of its centennial, she unwittingly embarks on a life-altering spiritual journey that unearths her small town’s dark secrets.

About: This script finished in the 11th slot on last year’s Black List. This is the second time Filipe F. Coutinho has made the Black List. He made it last year with his script, Whittier. Coutinho was mentored by Beau Willimon, who created House of Cards.

Writer: Filipe F. Coutinho

Details: 126 pages

Daddario for Jayne?

Daddario for Jayne?

I’ve been looking forward to reading this.

I love when writers take a highly specific subject matter and build a fun story around it. And I thought it was funny that the writer went so far as to say that our subject matter – paper jams – could actually teach us something about life.

And then, of course, there’s my memory of the greatest comedy scene ever shot, which was the guys in Office Space taking the printer out to a field and bashing it to pieces to the sweet vocals of The Geto Boys. Ever since then, printers have been in the team photo for the funniest things you could build a comedy scene around.

So I think this script has potential. Let’s see if I’m right.

Our movie is set in the small town of Fairport where the Von Brandt Paper Company has been operating for 100 years. The company specializes in making printers. More specifically, Von Brandt is one of the leaders in the industry for troubleshooting paper jams.

In fact, it has an entire department dedicated to fixing paper jams. As we’re told, paper jams are incredibly complex. Here, one of the characters explains it to us: “Paper isn’t manufactured, it’s processed. And that process is complex. First, you gotta turn the trees into wood chips. Then, you mash ’em into pulp and bleach it. And then you run it through screens and chemicals to remove all bio gunk until only water and wood fiber remain. That’s just for starters. Now consider this – in Spain, paper’s made from eucalyptus, but in Kentucky, Southern pine. And they’re expected to go through the exact same machine without any issues… Seems challenging enough, huh? Now multiply that by a million types of paper and factor in the 12 thousand steps that happen from the moment you hit ‘print’ to the moment the sheet lands on the tray. You ask me, it’s a miracle paper isn’t jamming all the time.”

Anyway, one day, a worker named Duarte Alves sees something come into his office and makes a run for it. He goes to the paper jam cemetery and watches as a gigantic industrial printer is pushed on top of him and he dies.

Cut to a day later an we meet detective Jayne Brubaker. Jayne is a no-nonsense type of gal. And while everyone else seems to think this was some sort of accident, Jayne believes there’s more at play here. So she starts interviewing all the people who work at Von Brandt. What she learns is that this place is so obsessed with solving the world’s paper jam problem that they’ve become blinded to just how severely this is affecting their employees. Because it isn’t long before another employee, Chad, dies mysteriously.

Just when Jayne starts making headway on the case, her boss, aka her father, comes in and says “Slow down.” He explains that Von Brandt is all Fairport has. If you expose it as some sort of evil murderous place, you could destroy the entire town. Jayne then has to decide if she wants to keep the status quo or do what’s right. A decision that becomes a lot weirder when Elvis enters the picture. Elvis, you say? Welcome to Jambusters.

One of the harder screenwriting things to discuss in any helpful way is “voice” and “writing style.” These are so personal and so subjective, the extent to which you can dissect comes down to saying you either like the style or you don’t.

But it’s a relevant discussion because it has an outsized effect on the read. Writing styles change how a story moves through your brain. To give you an example, imagine a story about a guy who moves back to his hometown after being gone for 20 years.

Imagine Kenneth Lonergan (Manchester by the Sea) writing that movie and then imagine Quentin Tarantino writing that movie. You’re envisioning two completely different movies in your head, right? That’s the outsized effect of writing style.

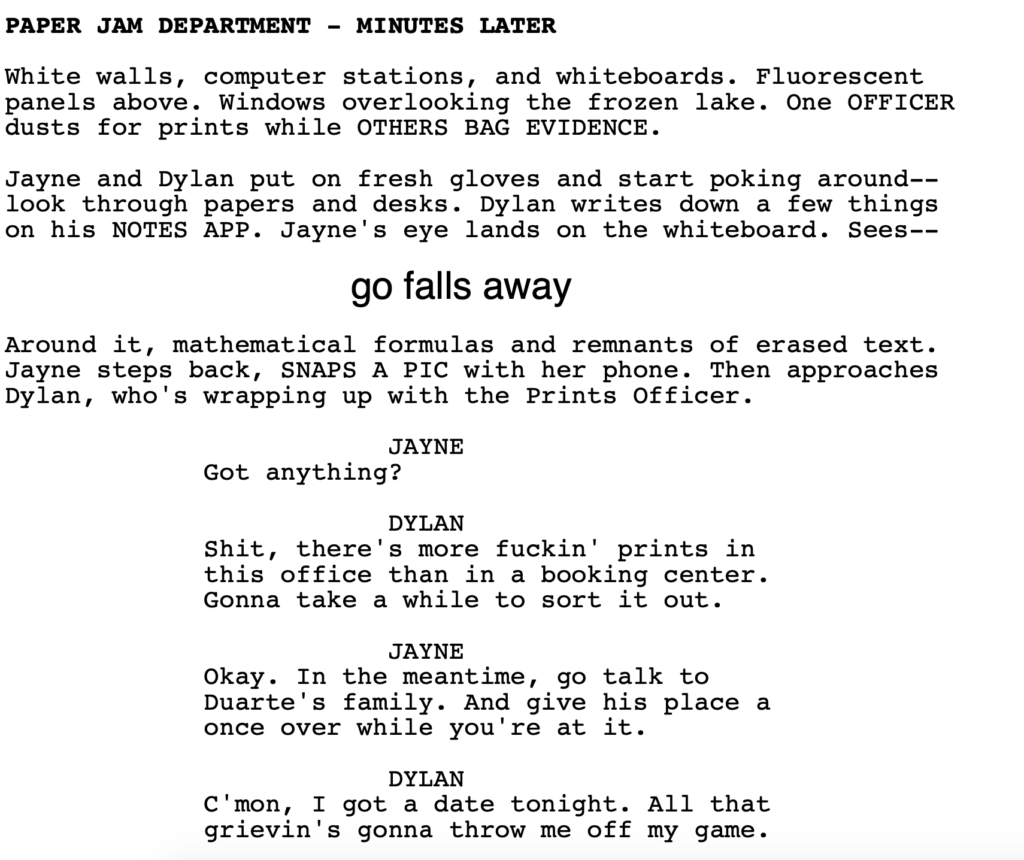

I bring this up because today’s script has a very chatty style to it. It’s kind of like reading someone with a colorful personality who likes to talk a lot and who has ADD. Here’s a quick example from the screenplay…

There’s nothing wrong with this writing style. I actually prefer it to the opposite, which is the super-simplified, “only-the-facts-ma’am” style. With that said, this over-stimulated style can start to grate on the reader if the story isn’t keeping up with it. Because it does take a lot of effort to read, which readers don’t like. So you start to feel like, I’m having to work harder than I usually do to get though something that shouldn’t be taking this much energy out of me.

And I guess this gets into a bigger debate about what screenwriting really is. It started out as purely a blueprint to make a movie. There was no personality at all in the writing because how does ‘personality’ help the set workers know how to dress the set? If you want the set to look a certain way, give us the facts and we’ll make it look that way

Of course, that changed over time, because the screenwriting business got more competitive and writers realized they could better keep a reader’s interest by adding a little personalization to the writing. They could use their voice to give their screenplays a little more pop.

It’s just important to remember that there’s a line by which you don’t want to cross. And that line is when the reader feels like they’re working harder than they want to to understand what’s going on.

And that was definitely going on here. Not a lot. But enough that I started to get aggravated. It’s not an accident that this script is 16 pages too long. What’s that old video series that used to get all that play? Girls Gone Wild? Well, this is Voice Gone Wild. Let’s not let this voice take off its off every ten seconds.

With that said, Coutinho makes a smart decision. He doesn’t just follow the daily exploits of someone who works at a printer factory. He gives us a dead body. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again. If your idea feels tame in any way, introduce a dead body. A dead body creates mystery and it introduces PURPOSE in to the story. Now someone has to look into that dead body. They have to find out how they died or how they were murdered. Which means we have a goal.

And I did enjoy some of the philosophical stuff about paper jams in comparison to the meaning of life. It did get a little weird, but it was amusing.

In the end, though, this script makes you wade through so much text to get to the relevant plot points, that it violates one of the most important rules of screenwriting, which is that a script is supposed to entertain the reader. The second it crosses over into making them work, you’ve lost them.

And I just felt like I was having to read way too much stuff to get to the point. I suppose watching Jayne share an impromptu dance with her husband isn’t violating any screenwriting laws. But I sure did ask myself after I read it, “Was that really necessary?” I found myself thinking that a lot.

This script is hard to describe. But if I were pressed to, I’d say it’s I Heart Huckabees meets Chinatown by way of Max Landis. If that sounds like your paper jam, check it out and let me know what you think!

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: “He’s gangly, with hips like doorknobs and unruly, brittle hair.” Sometimes we writers write stuff that looks good on paper but doesn’t make sense. And for whatever reason, we favor the “looks good” part over the “makes sense” part. Don’t ever do this. The “makes sense” part is always more important. Nobody knows what “hips like doorknobs” looks like. It doesn’t make sense which means, even if you have to switch in a more boring description that *does* make sense, you do so. Cause making sense is always the priority.

One of the most famous spec sales of all time. Why didn’t it get turned into a movie??

Genre: Dark Comedy

Premise: An ultra-masculine airplane mechanic’s wife leaves him for a fruity new age weirdo and must figure out how to get his life back.

About: This is a famous spec sale for a script that never got made. It comes from the spec sale king, Joe Eszterhás. It sold for, I believe, 2.5 million dollars in the late 90s. It was then rewritten by the writing team of Brent Brisco & Mark Fauser, who wrote the monster box office hit, Waking up in Reno, starring Billy Bob Thorton and Patrick Swayze. Okay, maybe it wasn’t a monster hit but there’s a rumor that at least 37 people saw the movie before it went to video.

Writers: Joe Eszterhás, Brent Brisco & Mark Fauser

Details: 122 pages (2001 rewrite)

The Spec King.

He’s a legend this man.

He was also a notoriously angry individual who got in a lot of fights with Hollywood execs. So it shouldn’t be a surprise that the main character in this movie, 46 year-old Frank Jessup, is also a hothead.

Frank is an airplane mechanic who loves his Cleveland Indians and who, one day, after heading out to fix an impromptu problem with one of the planes, comes home to find that it’s completely deserted. His wife, the nature-loving Connie, and his teenaged son, the hip-hop obsessed Frankie, have moved out.

Frank storms over to their new apartment to find that not only has Connie left him, but she’s also with some numb nuts named Jeremy. Jeremy is 2001’s version of a hippy. He just wants peace and for everyone to love each other, man. Which makes Frank really confused. Cause he wants to kill this guy. But Jeremy wants to be his friend!

After Frank gets thrown in jail for nearly killing Jeremy, he learns that he needs to take some sensitivity training after it’s discovered that a ton of people at work have complained about racist and sexist comments he’s made. Things really aren’t looking great for our protagonist.

The thing is, Frank is ignorant to everything that’s happening to him. He doesn’t understand what he did wrong. He doesn’t understand why his wife doesn’t like him anymore. He doesn’t understand why his comments at work are controversial. He’s just being his normal fun self.

Only when Frank goes through sensitivity training does he start to realize that maybe he’s crossed the line in a few areas. But even then, he thinks the world is being too damn wimpy. So, will Frank change and convince his family to come back to him? Or is he so far gone that this is who he’s going to be for the rest of his life?

One of the most confusing things that screenwriters had to deal with back in the day was that screenplays which were objectively bad would get sold for loads of money, sometimes north of a million dollars.

And they would see the subsequent movie, which would often be horrible, and they’d say, “Wait a minute here. This film is bad. Why does this sell for a million bucks and I can’t get the worst agent in Hollywood to call me back?”

The answer to this is kind of complex because there are half-a-dozen main reasons that bad scripts get purchased and bad movies get made. But when it comes to the case of Male Pattern Baldness, the answer is obvious. If you have the most successful spec writer of all time going to market with a new script, it’s going to sell for a lot of money regardless of the script’s quality.

You see, in the movie business, you’re trying to acquire commodities that push a project to the finish line – aka, the movie gets made. The more of these commodities you can acquire, the better the chance the movie has of getting made. Joe Eszterhás had gotten multiple scripts to the finish line when he wrote this script. So this is a commodity that’s worth paying a lot of money for. Just having that name on your project gives you a legit chance to get to the finish line.

But is this script really that bad?

No. It’s actually okay. But it’s not good enough to be turned into a movie.

I get the sense that was a personal project for Eszterhás. I looked at his wiki page and saw that he got divorced in 1994. So maybe he started writing this then?

The thing with personal projects is that they can either go really well or really badly. The authenticity and emotion that comes from a personal experience can be quite powerful. But it can just as easily cross into self-therapy, where the story is more about the writer dealing with their demons than writing an entertaining story. And I think that’s what happened here.

I suppose the script is built on a template that works – Your hero loses everything and must look inside themselves, realize what they’ve become, and try to become a better person. Heck, Alan Ball used this template to create a classic in American Beauty, although I’d argue Ball deconstructed the narrative in a more interesting way (Lester Burnham does some questionable things in his pursuit of changing into a “better” person).

But I noticed that about halfway through the script, the story had no more gas. I’m reading a scene where he’s having an argument with his wife and his kid and Jeremy and I realized, “We’ve already had this scene.” In fact, we’d had it a couple of times. That’s typically a bad sign for a screenplay. When you’re repeating scenes. Because it often means you don’t have enough plot for a feature.

The funny thing about this script is that it’s actually quite relevant to today. Frank is the embodiment of toxic masculinity. He lives in his own world. He operates by his own rules. He says what he wants to say. And he doesn’t care if anyone’s offended.

But it’s done in a way where they show real toxicity. He says something racist to a Mexican. He compliments a woman’s breasts at work. He’s openly violent. It’s actual real problems. Not the sanitized stuff you see today where if you ‘like’ a tweet from a Twitter user who once misgendered someone, you’re branded a Nazi, get your bank accounts drained, and are sent to the gulags in Russia.

It’s funny to see how much the line has moved since 2000. And, for that reason, I don’t think the script could be produced. It would require too radical of a rewrite. All the lines that Frank crosses, you’d have to write kinder cuddlier versions of them.

There are still screenwriting lessons to learn here, though. Eszterhás starts out with a head of steam. Read this opening scene and note how something is actually happening as we’re dropped into the story (Frank is on the phone dealing with an escalating work problem while his family tries to get his attention). That’s important to do with character-driven stories. It is imperative that you don’t start off with a boring scene.

And I loved the inciting incident. Normally, the inciting incident in this story would be Connie throwing up her hands and saying, “I can’t take this anymore. I’m leaving you.” It’s much more effective the way Eszterhás writes it, which is that Frank goes to fix the problem at work, comes home six hours later, exhausted, and finds that his entire house is bare. It really highlights the severity of what’s just happened.

And immediately after that, we get the confrontation scene, where Frank charges over to the new apartment and screams at Connie while getting into a fight with Jeremy. That’s a good scene as well. So the script starts out strong. It grabs you.

I also thought Jeremy was a clever character. Usually these characters are jerks. The fact that Jeremy is so nice throws the formula for a curve in a fun way. At one point a lawyer shows up at Frank’s house unannounced and Frank’s like, “Who are you?” He says, I’m your divorce lawyer. I’m the best in the business. Frank says, how do you know about my wife and I getting separated? He says, oh, Jeremy sent me over here.

If you’re wondering what the title means, it refers to a therapist who tells Frank that he has figurative male patten baldness. Which is when you’re too masculine. You have no feelings. You do whatever you want. You’re obsessed with sex. The therapist tells him, I can cure you of this.

Like I said, the script doesn’t have enough going on to warrant anything past the page 60 mark. It’s one of those scripts where the writer starts big out of the gate, but isn’t really sure where the script is going to go. And so every subsequent scene seems to have less punch than the previous one. It goes to show that even the best screenwriters can’t write their way out of a weak concept.

Script link: Male Pattern Baldness

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Character archetypes are meant to be played with. Whenever there’s an archetype in your screenplay, ask yourself if you can play that archetype the opposite of how they’re usually played. Because that will result in a much more interesting character. Jeremy being super supportive of Frank’s attempts to reconcile with his wife was one of the standout aspects of this screenplay because it is the complete opposite of what that archetype usually does.