I love The Bear. It’s an extremely well-written show. So I thought, let’s bring “10 Screenwriting Tips” out of retirement so we can learn what screenwriting tricks The Bear is using to be so goooooood!

1) Obstacle Mania – Whatever your characters’ giant goal is, your job, especially in a TV show, is to place as many obstacles in front of that goal as you can. The Bear, Season 2, does this better than any show I’ve seen in recent memory. The goal is to open a new fancy restaurant. We’ve got IRS issues. Fire regulations. Finding an investor. Open in just three months. Mold. Walls falling down. Hiring competent staff. The list is never-ending. Obstacles create UNCERTAINTY IN THE NARRATIVE. Which is what you want. You want the reader to be unsure if the characters can do it.

2) Put your characters where they least want to be – Where you find the most drama in a story is when you place characters in places they do not want to be. Richie, the screw-up of the family, hates order and responsibility more than anyone in the world. This guy only thrives in chaos and disorder. In season 2, episode 7, Carmy gets Richie a job in the kitchen of the best restaurant in Chicago. Needless to say, the restaurant thrives specifically on order and responsibility. You can see Richie boiling over just standing in this place. It is the antithesis of him. Which is exactly why we can’t look away. This episode, “Forks,” is my favorite episode of Season 2 because of this lesson.

3) Intense conversations work better when at least one of the people in the conversation doesn’t want to be there – Intense dramatic conversations about life don’t usually play well. They often feel self-indulgent and fake cause kumbaya “I’m all up in my feelings” moments don’t happen all that often in real life. So a way to make them more palatable is to have at least one of the characters in the conversation not want to be there. In season 2, episode 1, an “up in his feelings” Richie is downstairs in the basement feeling bad for himself. Carmy comes down to grab something and Richie blurts out, “You ever think about purpose?” Carmy looks at him and says, “I love you but I don’t have time for this.” But then he sees Richie is really in the doldrums and decides to stay, reluctantly. Richie then makes his big, “I don’t feel any purpose” plea, and Carmy’s not really into it. He has a million things to do. But he stays and listens to the best of his ability. Carmy’s half-interest is what makes this scene work. Cause if they’re both really into this conversation, it’ll feel false.

4) Compounding outside pressure – One of the things The Bear does really well is it places pressure on its characters. But that’s par for the course. Every character should have pressure on them. What The Bear does, though, is it compounds that pressure. It adds ADDITIONAL PROBLEMS to the characters’ lives, which makes every scene feel even heavier, even more important. In “Forks,” midway through the episode, Richie calls his ex-wife, who he’s secretly hoping to get back together with, to manage a situation with their daughter. And the ex-wife tells him that she just accepted a guy’s proposal. This is what compounding pressure looks like. You never let your character off the hook. And the great thing about compounding pressure is that now, whenever Richie encounters an issue in the restaurant, we’re more afraid he’s going to crack. Cause we know that there’s additional things going on in his life.

5) The Scene Agitator – I would be surprised if creator Christopher Storer has not read Scriptshadow Secrets because this man LOVES the scene agitator. As a reminder, the scene agitator is any element you can add to a scene that agitates the characters in some way. Storer rarely lets two characters just talk to each other. He almost always has a third variable in play. For example, in season 2, episode 7, when Richie calls his cousin, Carmy, back at the restaurant, to ask him some questions, the team’s fix-it guy, Neil, is trying to fix a faulty outlet wire, which keeps electrocuting him. So Carmy is trying to talk to Richie while occasionally stopping the conversation to yell at Neil. “Neil! What are you doing! Get away from that thing.” Neil is the agitator here, and provides a more unpredictable conversation between Carmy and Richie.

6) Pronouns and Role Play – This is a preview tip from my dialogue book. A great way to spice up dialogue is to have the characters in the scene playfully use the wrong pronouns as well as use role play, pretending they’re not the people they really are. It allows for a unique conversation that always feels more creative than the on-the-nose version most writers write. In season 2, episode 8, Ebraheim, an old-timer chef at the former restaurant who bailed when Carmy decided to upgrade the restaurant, comes back a couple of weeks before the new restaurant is opening. He runs into his old buddy, Tina, who still works there.

7) Nobody’s angry just because they’re angry. They’re angry because they’re scared – I read a lot of scripts where characters are angry because the writer wants an angry character. But they don’t think about WHY that character is angry. And WHY they’re angry is the whole ball of wax. Because most of the time, they’re angry because they’re scared. Cause they don’t think they can hack it. Like Richie. Richie is my favorite character in this show because of that inner conflict. He’s the loudest. He’s the harshest. He screams at people all the time. When he messes up, it’s always somebody else’s fault. And it’s all because he’s terrified. He’s terrified he’s going to be exposed for the scared little kid he actually is. So when a character is angry, give them a reason for being angry. I promise you, the character is going to come off as so much more genuine if you do.

8) Money makes the TV show go round – Money money money monaaaaay. MONNNAAAY. Money is a wonderful friend in any dramatically told story, but especially in television. The thing with TV is that it doesn’t have that ticking time bomb urgency that a movie can have since a movie is only 2 hours. With TV, the timespan is always longer and so we lose out on that urgency. You can compensate for this by adding a money issue. Your main character(s) should be under some sort of monetary deadline. With The Bear, in order to get the investment for the restaurant, Carmy has to agree that if his uncle isn’t paid back in full within 18 months, the uncle gets the building. Never having enough money is such a universal experience that we always relate to money problems in stories.

9) Make sure to balance the sour with the sweet – The Bear puts its characters through the wringer. It really whacks them up against the head with a lot of crap. If all you do, though, is hurt your characters, your reader will grow frustrated. We’re not sadists. We need good amongst your bad. And The Bear is good at this. It makes sure to intersperse the bad with a nice little occasional scene that gives you the warm and fuzzies inside. In the first episode of season 2, there’s a scene near the end of a tough episode where Sydney, the smart-as-a-whip prodigy sous-chef, runs after Tina, the old school “been here forever” cook who’s accepted her lackluster lot in life. Sydney asks Tina if she would be her assistant. And we just see Tina’s eyes light up when she realizes what Sydney is asking. It’s such a sweet moment as well as a NEEDED ONE. Because we need the sweet within the sour.

10) Scenes With a Lot of Characters In Them – The Bear has a ton of scenes with a lot of characters in them. For these scenes to work, you need to know who your CONTROLLING CHARACTER in the scene is. Your controlling character is the character who wants the most out of the scene. They have the big objective that’s driving the core of the conversation. So in Season 2, Episode 5, five minutes in, Uncle Jimmy (the investor) shows up to the restaurant to check on things. He walks into a room with, literally, seven other characters and everyone in the scene talks at some point. But the scene keeps coming back to Uncle Jimmy because he’s the controlling character. He is the one who wants the most out of this scene. He wants to know that they’re going to be ready to freaking open when they said they’re going to be ready. So that’s what drives most of the conversation, is his questions and directives regarding that topic.

100 dollars off a Screenplay Consultation (feature or pilot) if you e-mail me with the subject line, “THE BEAR!” carsonreeves1@gmail.com. What are you waiting for??

Genre: Action-Thriller

Premise: When her family is abducted, a disgraced submariner must pilot a narco submarine to its destination in less than eight hours or her husband and daughter will be killed.

About: Today’s writer is from Kansas City. He studied film at the University of Kansas. This script got him on last year’s Black List.

Writer: Andrew Ferguson

Details: 117 pages

Cobie Smulders for Cora?

Cobie Smulders for Cora?

In my newsletter I said, “Someone needs to write a new sub spec.”

Well guess what? Someone has!

Let’s see what it’s all about.

27 year old Cora Cameron was training to be a submarine captain when she contributed to killing her partner in an underwater military training exercise. Ever since, she’s been a heavy alcoholic who desperately is trying to have a relationship with her young daughter, Penny, and her estranged husband, Nolan.

One day she’s kidnapped and taken down to Baja, Mexico, where she’s plopped down into the biggest private narco sub in the world. This thing is gigantic. But it’s also brand new and still has some kinks to be worked out. Cora receives a call from a mysterious voice that tells her this is his sub and she has exactly eight hours to deliver it up north to California. Or else her husband and daughter are dead meat.

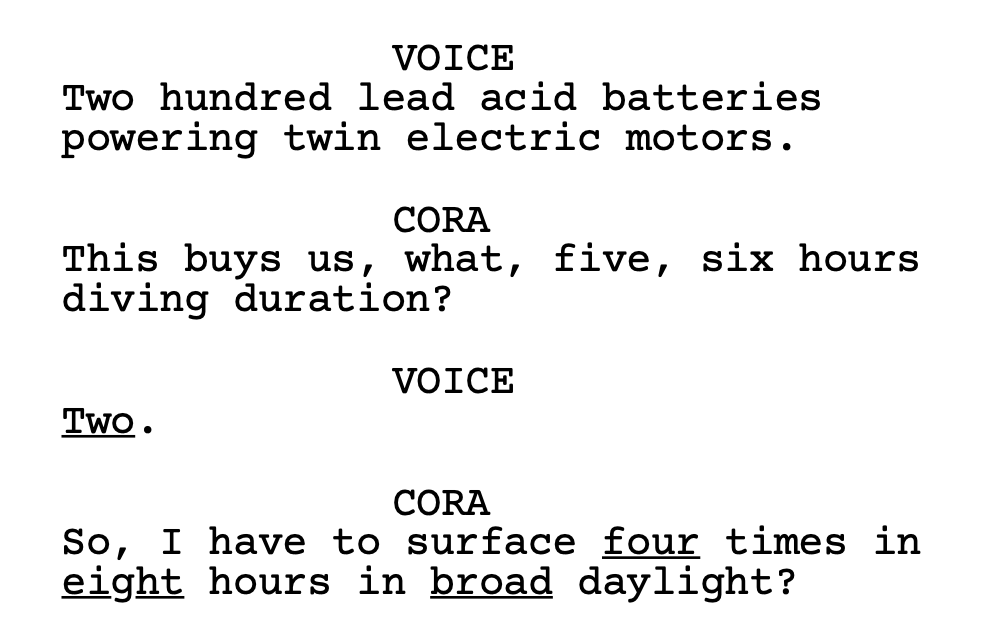

Cora is joined by a Mexican crew of thugs. Only one of them speaks English. And none of them trust her. To make things worse, the DEA is onto them immediately. So they start flying in planes, floating in boats, all to track this sub. Gamble, the nice government guy, is looking for any way he can help Cora survive this. Huxley, the bad government guy, wants to blow the sub out of the water and end this immediately. Because Cora has to surface her cheaply-made sub every couple of hours, Huxley keeps getting Hulk-smash opportunities.

But then something happens that truly throws everything off (spoiler). It turns out it’s not drugs that they’re hauling, but rather, explosives! And not just small explosives. Collectively, these explosives can take out a pretty big target. The question is, what is that target? And was this always going to be a suicide mission regardless of whether Cora followed the rules? One thing’s for sure. Cora must rely on every trick of her failed submarining career to get out of this mess!

The other day I was watching Shark Tank, a show where people stand in front of a panel of billionaire businessmen and try to get them to invest in their small companies. In the first segment, some woman was pitching her ice cream business. As soon as she was finished, the sharks started asking all these business questions with elaborate acronyms like, “What’s your ROIBMC?” Or, “What’s your bottom top out reverse expectation level for 2022?” The poor woman had no idea what they were talking about and quickly crashed and burned.

Cut to the next team, two flashy tech guys selling something for your car that lowers emissions. The sharks asked them the same questions. But this time, the guys not only had answers, but threw back unique financial terms about the emissions market even the Sharks didn’t know. They ended up getting a deal.

Why do I tell you this?

Because, in screenwriting, you gotta be able to sell us on the fact that YOU ARE AN EXPERT ON YOUR SCRIPT. If you’re writing about submarines, you have to convince me that you are Mr. Submarine Man. I say this as someone who’s read around 75 submarine screenplays. Cause I can PROMISE YOU there’s a big difference between the ones where the writer knows submarines, and the ones where they don’t.

The ignorant writer ignores the details about subs because THEY DON’T KNOW THE DETAILS. And when you ignore the details, you are, by definition, writing a generic story. Have have ever heard of a generic script that has taken the world by storm? Cause I haven’t.

Everything about the submarine stuff here is top notch. We’re repeatedly getting specialized info that only a sub expert would know.

For that reason, I BELIEVED in the story. And believing is critical. Cause it’s what suspends disbelief. But it’s only half of the game. The other half is writing an entertaining story.

One of the best ways to write an entertaining story is to KEEP YOUR READER OFF-BALANCE. The more your reader feels like they’re standing on solid ground, the more you’re losing them. You want the reader to feel off-balance and unsure. That’s when you have them. Think of movies like Memento and I Care a Lot and Parasite and Missing and even Emily the Criminal. Those movies never allow you to stand on solid ground. You’re always a little unbalanced. And that’s great.

Can you get away with not doing this?

Sure.

If you’ve set up characters who we love and a situation we’re emotionally invested in, you don’t need to keep us as off-balance. This is what Taken did so well. We liked her. We liked him. So we wanted him to save her. That’s all we needed!

The problem with storytelling is that even when you set up your characters perfectly, there’s this weird x-factor that you have no control over where, sometimes the characters don’t click with the reader. Even if you’ve done a “good job” with them. Which is why I encourage writers to do your best in the character department and then GIVE YOURSELF INSURANCE with some fun unexpected plot developments along the way.

I’ll give you a great example from the show Hijack, on Apple, about a guy trying to get home but he ends up on a flight that gets hijacked. (Spoilers) The first episode is a relatively straight-forward hijacking. Nothing happens that we don’t expect to happen. As the episode goes on, the main character is watching all of the hijackers carefully.

At the end of the episode, as we’re cutting back and forth between the plane and our hero’s family in the UK, who have been made aware that he’s on a hijacked plane, a cop asks the wife, “What does your husband do?” Then back on the plane, we see our hero stand up in the aisle and brazenly approach the hijackers. Cut back to the family where the wife and son say, “It’s complicated what he does.” “Well, what is it?” “Basically,” they say, “He’s a negotiator.”

We then cut back to the plane where the hijackers see our hero approaching, point a gun at him and ask him what he’s doing. He tells them that as the people on this plane get more rowdy and as they deal with more on more issues on the ground, that it’s going to get harder and harder to accomplish their mission. “So,” he says, “I’m going to help you hijack this plane.”

BOOM.

This is what I mean by a twist that unsettles the narrative. It puts the reader on edge. They’re no longer sure what happens next.

That’s how I judge a lot scripts like Subversion. Do they keep me off-balance? Subversion has one big twist. Which is that they’re not delivering cocaine like they originally assumed. They’re delivering a bomb. Which is a pretty good twist. But is it as good as Hijack? No. Which is a reminder that there is a SCALE to these choices. Not any old unexpected choice will do. You have to be creative. The more imaginative you are than the next writer, the better you’re going to do in this business.

So, for Subversion, I thought it was a solid script. There were a lot of interesting ideas in here, such as the fact that they had to keep surfacing throughout the journey, which put them in danger. Half the movie is about the government people who are trying to neutralize the sub and I liked that some of them wanted to kill Cora and others were trying to pull this off without any causalities. It made for a lot of suspenseful moments.

You wouldn’t be wrong to call this “Die Hard on a sub.” In fact, if the lead character was a 40 year old man and this spec was written in 1994 as opposed to 2023, I have no doubt it would’ve sold for 1.5 million dollars. But, times they have a changed. It’s still a decent script. It could even be a movie. We’ll have to see. I just wanted it to be a little more off-balance.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The better you are as a writer at manipulating emotions – creating characters that make readers *FEEL* things, the less flashy sh— you have to do in your script. If you’ve been told more than once by readers that they’ve teared up reading your scripts, then you can write scripts like Taken and not have to add a lot of flashy plot developments. But if you’re weak with character? You’re more of a concept guy? Or plotting is your thing? Then you definitely need to add more twists and turns. You’ve got to shock the reader more because, the reality is, they’re probably not all that invested in your character’s journey.

Genre: Action/Adventure

Premise: Indiana Jones is pulled into one last adventure when his goddaughter asks him to help her find a dial created by Archimedes that has the power to travel through time.

About: The fifth and final Indiana Jones film, which is said to have cost 280 million dollars, pulled in just 60 million dollars over the weekend, continuing a trend of weak box office showings this year. This is the first Indiana Jones movie not directed by Steven Spielberg. It was directed by James Mangold, who Lucasfilm was so happy with that they hired him to make a Star Wars movie about the origins of the Force.

Writers: Jez & John-Henry Butterworth AND David Koepp & James Mangold (characters by George Lucas and Phillip Kaufman). Phoebe Waller-Bridge is said to have done some script work as well

Details: 150 minutes

As I approached the digital ticket kiosk to purchase my entry into Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, I attempted to bypass the annoying button prompts by simply humming the Indiana Jones score, figuring the kiosk would know what movie I wanted and simply ask for my credit card info.

Not only did that not happen, the pleasant pimple-faced teenager tasked with monitoring the kiosks came over to ask me if I was okay.

But you know what did happen?

I got to see a good Indiana Jones movie.

It’s unfortunate that Indiana Jones number 5 wasn’t number 4. Cause number 4 was a disaster of epic proportions. It was so bad, in fact, that the screenwriter, David Koepp, came out and said that he knew he was going to be taking bullets for the screenplay. That NEVER happens, where the screenwriter admits before the movie has come out that it’s bad.

Dial of Destiny, even though it’s not a perfect film, is a film where you can tell they did everything in their power to write a good screenplay.

The thing with the scripts for these gigantic blockbuster movies is that they’re often less about writing a cohesive story than they are pleasing the 10 major creative forces on the film, and patching together the ugly disconnected mess of ideas from those forces with bridges just strong enough to keep the movie together.

That’s not the feeling I got from this movie at all. Maybe it’s because this was the last Indiana Jones and they didn’t have to worry about setting up future storylines. Which meant they could write the best story possible. Or maybe they just sat down and kept at it until they got the screenplay right.

The film is set in 1969. I think Indiana is 75 years old in this iteration. He lives in New York by himself in some apartment downtown. Unlike the glory days when he was young and sexy and girls used to blink at him with “I luv you” written on their eyelids, now Indiana is old and no one cares about his lectures anymore. Which is probably why he retires.

Indiana gets a drink at a local bar and is approached by Helena, his goddaughter. Helena tries to get Indiana to don the hat and whip one more time to search for something called the Antikythera, a dial that Archimedes created that is rumored to be able to manipulate time. Indiana then surprises Helena by bringing her back to the school and showing her that he already has the Antikythera. Or, at least, one-half of it.

This is when it’s revealed that Helena is not a very cool goddaughter. She steals the Antikythera and heads off to Africa to sell it. Around this time, Indiana learns that a Nazi named Dr. Voller is looking for the Antikythera as well and may have some nefarious use for it. Which means that old Indy will have to don the hat and whip again. And off he goes.

In true 2023 blockbuster McGuffin fashion, there are multiple McGuffin pieces to search for. Indy and Helena reluctantly join forces, traveling around the world to find out where the second half of the Antikythera is. Just when they find it, Dr. Voller sweeps in and takes it, and then takes *them* on a time-traveling trip to the beginning of World War 2, where he plans to win Germany the war. Except they don’t end up in 1939. They end up in 214 BC. And not even Indy knows how they’re going to get back home from here.

Here’s the thing about this movie. It’s probably the best Indy movie outside of the first one. With that said, I’d still rather watch the first three again than I would this one. How does that make sense? Because an action movie with an 80-year-old star just doesn’t work. To be fair, Harrison Ford is probably the only actor on the planet who could make an 80-year-old action movie work. But it still just feels wrong. Which is why I’d still rather watch those first three films.

But anyone saying this isn’t a good movie is crazy.

It’s a good movie. Maybe even a really good movie.

And I’m going to give you a comp so you understand why this movie is good. Jurassic World Dominion. Both these movies are trying to do similar things. They very much operate in the same universe. They even try to rip off a combo of Indiana Jones and Han Solo to make that awful pilot character Kayla Watts.

The difference is that this screenplay is a million times tighter. Jurassic World Dominion is the bad version of Dial of Destiny. It’s what could’ve happened if bad screenwriting would’ve reined.

The McGuffin was cool. There were always goals, stakes, and urgency. The bad guy was cool. The dynamic between Indiana and Helena was strong. Keep in mind that this was the first we’ve ever seen a female co-star with Indy that wasn’t a love interest. That alone made their dynamic feel fresh. Most importantly, the writers did a really good job keeping the reader up to date with what was going on.

I always knew what leg of the story we were on and what they were after. This is something Hollywood has gotten so lazy with recently, especially in the last phase of Marvel films, where the plot not only got convoluted, but the writers didn’t prioritize keeping you up to date with what the characters were after and why it was important. These writers on Dial of Destiny did a great job of that.

It sounds like some people had a problem with Helena. Like I said, I thought the dynamic was interesting between her and Indy. I always look for twists on the conflict between the movie’s primary team-up characters and this movie had that. If Helena would’ve just been some random chick who hated Indy and that’s where the conflict came from, that would’ve been boring. The fact that she’s family, though, adds another layer. It creates a “positive” that’s pulling at their dynamic as opposed to just a “negative.” I liked that.

I just want to take a moment to appreciate what’s happened in Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s career. Phoebe Waller-Bridge was a nobody until someone forced her to write this play called “Fleabag,” which she then turned into a show, which received a lot of acclaim, which got her meetings everywhere. And the next thing she knows SHE’S SHARING SCREENTIME WITH HARRISON FORD ON AN INDIANA JONES MOVIE.

ALL THIS HAPPENED BECAUSE SHE WROTE SOMETHING. I said the same thing about Taylor Sheridan in my newsletter. He was a nobody. Now he owns a ranch as big as Los Angeles. All because he wrote something. Everybody who’s reading this right now. Know this: You have a very powerful tool in your hands. If you use it well, who’s to say you can’t be on a giant franchise set in three years? It seems impossible but it obviously isn’t. Phoebe Waller-Bridge is proof of that.

Okay, back to the review.

Some people didn’t like the crazy third act. A few of you will probably wonder how I can prop up this screenplay with a third act this bonkers. I’ll admit that the third act doesn’t quite work. The movie didn’t do a good enough job setting it up. What does this time and this war really have to do with Indiana Jones’s legacy?

In regards to screenwriting, though, here’s the way I see it: Good writers take risks. They take big swings. So I admire Mangold and all the writers who worked on this taking a big swing like that. It didn’t quite work. Okay. But I’d rather take that big swing than aim for that double out to right-center field. If you’re going out, as the Indiana Jones franchise is, go out swinging!

This is the second best-written Indiana Jones movie of the five films. Period. But, as a movie, it’s limited by its 80-year-old action star. Which is why I wish they would’ve made this the 4th film and ended the franchise there. Indy at 63 could’ve made everything here a lot more convincing. RIP Mutt.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Pacing vs. Character Development. You’ll often have to balance how much character development you can include in a script versus how fast you can keep your story moving. One of the problems people had with Helena is that she’s very capable in dangerous intense action-packed situations. But how? We’re not given enough information on that. Here’s the answer: I can almost guarantee that that information was in earlier drafts of the script. But they needed to keep the pace moving. And when you need the pace ratcheted up, the first thing that goes is character development on SECONDARY CHARACTERS. You don’t take character development away from your hero. You take it away from the other characters. Which is why Helena feels a little thin. In the end, they left us with some quick mug shots of Helena, which indicated she did have a rough and tumble past. But it wasn’t enough to truly explain everything she was able to do. In a perfect world you would have both pace and character development. But if you have to choose, script pace is more important than secondary character development. So lean towards pace. A sloggy script read will negate any care we have about your characters anyway.

Note: I am taking the holiday off tomorrow. Happy 4th everyone! Seeya Wednesday!

Genre: Teen Comedy

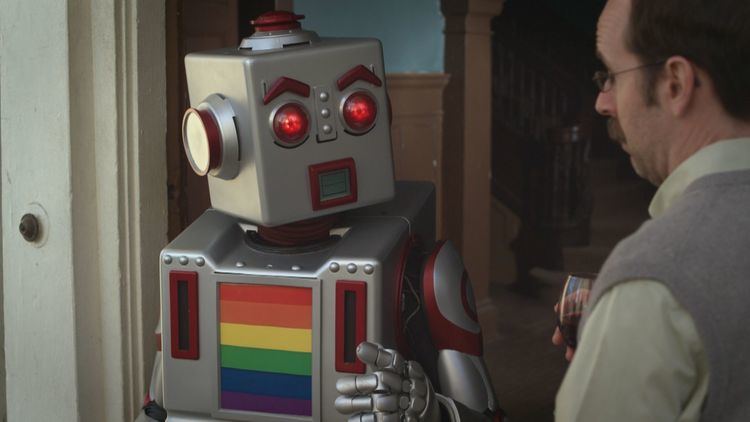

Premise: When two high school seniors discover a robot from outer space, they ignore its warning of an imminent alien invasion and reprogram it to help them score with chicks!

About: This is the logline that won the June Logline Showdown. Congrats to E.C. for the big win. He had to beat out six contestants instead of the usual four. So good job, E.C. Next month’s (July) logline showdown is for TV pilots. If you have a TV pilot logline you would like to enter, e-mail me at carsonreeves3@gmail.com with your title, genre, and logline, by Thursday, July 20th, at 10pm Pacific Time!

Writer: E.C. Henry

Details: 118 pages

Not many people had E.C. destroying the Logline Showdown competition on their bingo cards. Yet here we are. His win comes with a collective question from the Scriptshadow community: Does the script contain lit expression, E.C.’s trademarked writing style that includes varied colorful fonts? I can answer this question, which will excite some but upset others. Because this script was a written a decade ago, it is PRE-lit expression.

Now, on to the logline itself. Why did this logline do so well? Obviously, it’s funny. A robot shows up and says, “Your entire world is in danger,” and the guys respond by reprogramming it to help them score some ladies.

But I think there’s a deeper level to this concept that elevates it above just a quick laugh. Which is that, to a 17 year old male high school virgin, getting laid is EVERYTHING. It is all you think about. So, in a weird way, there’s this universal truth to their clueless decision. For them, OF COURSE getting laid is more important than the impending end of the world.

Now let’s check out if the script is any good.

High school teens, Chip, and his best friend, Dennis, are trying to make it through senior year. Chip is stuck with a girlfriend, Gretchen, who he doesn’t like. Who he really wants is the prettiest girl in school, Daphne. The problem is that Daphne is with cool jock, McGroover.

So Dennis and Chip try to come up with creative ways he can win Daphne over, which include sneaking up to her bedroom unannounced wearing a Three Musketeers outfit. And what do you know, it kinda works! Daphne thinks Chip’s gesture is creative and gives him a kiss through the window.

Meanwhile, a billion miles away, we meet an alien race of hawk-winged people called the Teltides, who send a scout to earth, who immediately impersonates a father in the neighborhood named Mike. On that same planet, an underwater species sends their robot, Bubblehead, to warn earth what the Teltides are up to – which amounts to destroying humanity.

When Bubblehead arrives, it is Dennis and Chip who first run into him. And right as they do, Bubblehead stumbles out of his ship and short-circuits. So the friends take him back to Dennis’s where Dennis works on him and brings him back to life. The annoyed Bubblehead warns them about the alien invasion but Dennis and Chip ignore him and bring him to school.

Hilariously, bringing a walking talking robot to school doesn’t provoke much attention. Even the teachers seem okay with Bubblehead hanging around. When a big party then gets announced, the best friends realize that their female problems are going to come to a head. Will they be able to overcome them? And, oh yeah, will the aliens attack and destroy the world?

I could sense E.C. was a little nervous about this review. I think we’d all be nervous about revealing decade-old writing. But I remember Harrison Ford promoting the 1997 special edition of Star Wars where a previously unused scene of him would be placed in the movie. Ford was asked whether he was nervous before the screening and he said, “Yeah,” defiantly. “It’s 20 year old acting.” If Harrison Ford can be afraid of an extra scene with Han Solo, I’ll allow E.C. to be afraid of an old script.

So, Bubbledhead Saves the Day is similar to a lot of the stuff I read from E.C., which is that it has these brilliant little moments but they get usurped by issues with the storytelling. For example, when Bubblehead is first called upon to give his opinion on Chip and Dennis, this is what he says: “Fine. I’ll tell you what I think. You are a conspirator. A man of low, moral character.” And then: “That’s right. I came to this planet with a message of dire importance for the leaders of this world to consider, yet those who discovered me saw it more fitting that I be reduced to serving typically overpriced, caffeinated beverages to their fellow members of this low order of education, as a means of subversively elevating their own social status amongst their peers.”

This is EXACTLY what I was hoping for when I read the script. A goofy funny robot that these guys are trying to use to their benefit.

But there’s so much standing in the way of us getting that. For starters, there needs to be 70% less description in this script and 70% more dialogue. High school comedy scripts are DIALOGUE-DRIVEN SCRIPTS. The only time there should be a lot of description is during the set pieces. Otherwise, I shouldn’t see any descriptive paragraphs at all. It should be all dialogue.

In fact, the majority of this script should’ve been ONLY Dennis, Chip, and Bubblehead talking. If this was a dialogue script that had these three arguing with each other 90% of the time, it would’ve been hilarious.

To E.C.’s credit, he added an element that I didn’t expect, which was that Bubblehead is resistant to his programming. Which I think is perfect for a 2023 version of this movie, because you could have Bubblehead be a stand-in for the ultra-socially-progressive Chat GPT, which doesn’t want these guys hitting on women. It could be giving them all the “socially acceptable” advice to pick up women, which of course never works. That could be really funny.

But, none of that stuff matters when I can’t even get a feel for who the main characters are in the first act. I thought Mike and Todd may have been the main characters at first. I didn’t even know Dennis and Chip were best friends until the second act, when we actually start getting scenes of them together.

I understand that writing a high school comedy is tough because you’re going to have a lot of high school characters in the story. And you have to introduce them somewhere and somehow. But those introductions shouldn’t come at the expense of us understanding who our lead characters are.

I can’t emphasize this enough. If your first act is confusing in any way, it’s very hard to recover from that. It’s like trying to recover from a bad first impression. The other person has already given up on you. I had to fight my way back into understanding this story after the first act.

And the fix is easy. 75% of the first act, focus on Chip and Dennis. Use the other 25% to introduce the other key characters. And then you can always introduce anyone else who didn’t make the first act at the beginning of the second act.

The other major faux pas is that we’re not delivering on the promise of the premise. I didn’t start getting anywhere close to the logline I read until page 60. And even then, it wasn’t enough. Bubblehead is probably your funniest element and he’s barely in the movie.

That’s not to mention that Chip isn’t even having problems with women! He’s got two women on his jock! If the whole premise is that these guys need help to get laid, then let’s show them as cute hopeless incels. They can’t get women to notice them for their life. Actually, now that I think about it, I don’t even think that Dennis cares about getting laid. Which is supposed to be the point of the movie!

So, unfortunately, this didn’t have the necessary foundation to breathe life into the fun premise. I still think it’s a great idea. But it needs a reevaluation and fresh approach in order to work.

But one more prop for my man, E.C. Anybody who names their principal character, “Principal Bumpkins,” gets a smile from me.

Script link: Bubblehead Saves the Day

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: It is critical in genres (high school movies, war movies) that have a large group of central characters, that you really strategize how you’re going to introduce them so that they’re all unique and easy to identify. Cause, as readers, if we’re meeting 15 high schoolers, how easy do you think it is for us to remember who’s who? And how all those characters relate to one another? It’s not easy at all. So introduce your main characters first if possible. Give them big luxurious descriptions so we know they’re important. Give them names that are easily differentiated from one another, and that, hopefully, sound like the person. “Waldo,” for example, would place the image of a nerd in the reader’s head. And just be very specific and detailed in regards to how everyone is related (Joe is best friends with Frank. Emma is the daughter of John). You have to hold our hand with that stuff because it’s some of the easiest stuff for the reader to forget.

We’ve got aliens. We’ve got submarines. We’ve got some criminally affordable notes to the lucky few who e-mail me quickly. We’ve got the COVER FOR MY NEW DIALOGUE BOOK. That’s right. It’s really happening! I share my thoughts on the new Zendaya tennis movie trailer, that controversial Taylor Sheridan profile in The Hollywood Reporter, and I review yet another short story that sold, this one directed by one of my favorite young horror directors.

Unfortunately, there will be no official post today (Thursday) so you’ll have to get your full Scriptshadow fix from the newsletter. However, don’t worry. The Scriptshadow week is not over because tomorrow we review our Logline Showdown winner: Bubblehead Saves The Day – “When two high school seniors discover a robot from outer space, they ignore its warning of an imminent alien invasion and reprogram it to help them score with chicks!”

If you haven’t received this newsletter or haven’t received any, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and I’ll add you to the list!