Genre: Romantic Comedy

Premise: Maggie finds herself the target of her sister’s wedding-thirsty bridesmaids after unintentionally catching the bouquet, messing up the bride-to-be queue.

About: This script finished in second place in this month’s Logline Showdown. We have a new Logline Showdown every month. The deadline for the next one is Thursday, June 22nd, 10pm Pacific Time. If you want to participate, send me your title, genre, and logline. The script *does* have to be written as the winner will get a review. You can send all entries to carsonreeves3@gmail.com

Writer: Kevin Revie

Details: 88 pages

The Hailster for Maggie?

The Hailster for Maggie?

Okay, so we had a snafu behind the scenes this week. Adam, who won with his script, The Dinosaur War, had been submitting the script to Logline Showdown for a while. At one point, he was submitting it as a feature. And this time, he was submitting it as a pilot.

Except I didn’t list it as a pilot. I listed it as a feature. Since everybody voted on it as a feature, both Adam and I decided that it shouldn’t be featured this week, which means the second place script, Petal to the Metal, is stepping up to the plate for this week’s review.

I’m actually excited about this script. I’m in the mood for something light and fun. And we don’t review a lot of romantic comedies around here. So I’m curious what Kevin has in store for us.

27 year-old Maggie isn’t the wedding type. So she’s far from thrilled that she has to go to her sister, Sierra’s, wedding. And she’s even less thrilled when she inadvertently catches the flower bouquet, anointing her as the next single lady to put a ring on it.

Not long after this happens, Sierra’s wolf-like bridesmaids, Evie, Zara, and Kira, get dumped by their long-term boyfriends. They immediately believe that some sort of curse has occurred because Maggie caught that bouquet.

So they conspire with Sierra to find a man for Maggie. The sooner they can marry her off, the quicker they can get back in line for their own marriages. They go to dating sites, find some dudes, and send the dudes off to pretend-bump-into Maggie and work their charms on her.

There’s only one problem. Maggie’s gay! She doesn’t want any sausage with her eggs. And when she finds out that the men are only coming on to her because of the evil bridesmaids, she does a reverse prank where she pretends to get engaged to one of the men, only to then throw it in the girls’ faces with a big fat “PUNK’D!”

After the fallout from the punking, Zara confronts Maggie, wondering why she can’t just get married so the rest of them can get married… BUT THEN KISSES MAGGIE!!! Maggie’s down with it and she and Zara engage in some extracurricular activities. But afterwards, Zara is unsure if she wants to make their new love public. The uncertainty of their relationship pushes us towards the big climax where Zara will either go public with her feelings or take the more traditional route in life.

Man, this was a wild one.

I don’t know what I was expecting, exactly. But it is definitely not what I got. I’m still trying to figure out if that’s a good thing or a bad thing.

I guess we should start with the main character, since that was the topic of yesterday’s article. I liked Maggie. She’s the one getting pushed around in this story. So there’s a natural inclination to root for her.

But I wasn’t sure if Maggie was the main character after the first act. I don’t know if she’s the main character after reading the whole script!

Let’s start with that first act, though.

We don’t meet Maggie right away. We only hear her voice as she narrates her sister’s life. We never see Maggie’s own everyday life, the section of the script that best shows the reader who your hero is. And then, even after the big “catching of the bouquet” moment, we shift our focus to these other girls – Evie, Zara, and Kira.

They then control the second act. They are the active characters. It is their goal – to find a man for Maggie and accelerate the courting – that drives the story.

If the first act barely focuses on Maggie and the beginning of the second act is driven by three characters besides Maggie… then who’s the main character here? Does this movie have a main character? Or is it meant to be an ensemble?

I still don’t know the answer to these questions.

Then, when you throw this sidewinder of a twist at us – that Maggie is gay – we’re really unsure what’s going on. After that reveal, the original concept disappears. We are in a completely different movie than the one we started with.

Then you have Zara revealing that she’s gay too! And that she likes Maggie! Which was an interesting way to go but it wasn’t set up at all. There was no official setup that Zara was gay or interested in Maggie. So when Zara plants a smackaroo on Maggie, it feels random.

Not to mention, Maggie comes out of that kiss looking bad. All we’ve seen so far is Zara be horrible to Maggie. And the second she kisses Maggie, Maggie’s down with it??? How bout showing a spine? Telling her to f-off for being such a terrible person to her. Rewarding awfulness does not endear us to your hero. Assuming Maggie is the hero!!

I was trying to think of a comparable movie that had this structure. It started off as one thing and became something else. The 40 Year Old Virgin comes to mind. That started off as a straight comedy with this guy trying to get laid for the first time. Then it shifted into a rom-com with him in a relationship.

But I’m not convinced this plot was as smoothly executed as that one. That plot felt planned. This plot felt like things were being thought up on the fly. That’s usually the case when a script deviates heavily from the original concept because the writer runs out of plot for that storyline and has to come up with something else to keep the keys depressing.

Then we’ve got this logline issue. The logline to Petal to the Metal is misleading. I think I would’ve enjoyed it more if I knew what was coming. So something like: “When a closeted 20-something unintentionally catches the bouquet at her sister’s wedding, she screws up the bride-to-be queue, resulting in the furious wedding-thirsty bridesmaids taking control of her dating life in an attempt to get her married ASAP. “

I know, it’s long. I would revise it a few times before sending it anywhere. But at least it represents what the script is. Readers can get pretty upset when the script is different from the logline.

Overall, I thought this script was okay. It’s too messy to get a ‘worth the read’ though. And I would’ve preferred to read the script I was promised. But it has its moments. It had a few lines I genuinely laughed out loud at, like this one: “I talked to an AI chatbot yesterday while drinking a sangria alone. That’s not okay.”

Now that you know the actual story, you can go in better prepared than I did, which will probably mean you’ll enjoy the script more.

Script link: Petal to the Metal

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Economy of words. Economy of words is SO IMPORTANT in comedy because comedy scripts must be easy to read. There were occasional lines in Petal to the Metal that violated the ‘economy of words’ law, like this one: “The bouquet, notably rose-less and stem-wrapped with ample precaution, comes HURDLING toward Maggie.” Why not just, “The bouquet comes hurdling toward Maggie?”

Or, on the dialogue end, we get lines like this:“Well, this is confusingly unnerving.” Why not just, “Well, this is unnerving?”

There will always be times when you’re more verbose. But, for the most part, screenwriting is about economy of words, saying as much as possible in the smallest package possible.

Back when I used to write screenplays, I would send them out to people and, just like many of you, be baffled when they weren’t met with unending praise.

At first I thought everybody was crazy. Don’t you understand what genius looks like!? But once reality set in that I wasn’t ready to break through the ranks and start rubbing shoulders with Shane Black and Spike Lee, I started looking at my screenplays analytically for the first time. What was it that I wasn’t giving the reader?

It turns out the answer was “a lot.”

And thus began my obsession with decoding the screenwriting matrix, a journey that would lead me to start reading screenplays, and then, later, analyzing them, which, of course, led to Scriptshadow.

Now that I’ve read 10,000 scripts, of which I’ve consulted on and reviewed thousands of, I’ve been able to isolate a handful of things that have the most impact on a script. These are things that you should be paying the bulk of your attention to when writing as they have an outsized impact on the quality of your script.

The most important of these is the one I’ll be writing about today: write a main character we want to root for

I was reading a script not long ago and the story itself was pretty good. If you just looked at the plot and the fantasy setting, you would’ve liked it. But I didn’t like it. And the reason I didn’t like it was because I didn’t like the main character. Which I explained to the writer. “You’ve done a good job with this story but I checked out on page 5 because I was put off by your main character.”

I give this note quite a bit. You’ve seen me give it here on the site a number of times, I’m sure. The issue is that main characters are usually in every scene. So if you don’t like them, why would you like any of the scenes they were in? And if they’re in every scene, why would you like the script?

But this isn’t another article about how to write a likable/interesting main character. This article is about why we write unlikable characters in the first place yet have no idea we’re doing so.

We do this because WE LIKE OUR MAIN CHARACTERS. Of course we like them. WE WROTE THEM! Why would we write someone we didn’t like? And therein lies the problem. We’ve decided our characters are likable without evidence. Just by writing them into existence, we assume that everyone will feel the same way we do.

There is no character a writer is more blind to than the main character. Sure, it’s the character they know best. But what they forget is that the reader only knows a fraction of the information about that character that the writer does. All the reader has to go on are the actions of the character. And if those actions don’t reflect anything that is likable, interesting, or compelling, we will not like your main character. And then your script is screwed.

As a screenwriter, your job isn’t to throw things on the page and hope for the best. You have to plan out how to persuade the reader so that they experience the emotions you want them to experience.

That means when you’re writing a character, you’re carefully plotting out what they’re going to do inside those first four scenes that is going to set the foundation for how the reader sees them.

I’m telling you, if you’re not obsessing over those early scenes and what your protagonist is doing in those scenes, you’re not screenwriting correctly. Those are some of the most important scenes in the screenplay.

If someone were to sit you down in a court of screenwriting law and make you give an argument for why people would like your character, you should be able to point to specific moments in those scenes that make your hero likable.

Let me give you an example. Imagine a really mean bully. Now imagine that bully embarrassing someone and reveling in it. The person they embarrassed? We are going to root for them. Cause nobody likes bullies. And everyone is sympathetic to someone who is unjustly bullied.

That’s something clear and convincing you can point to in a Screenwriting Court of Law for why people would root for your hero.

And it doesn’t even need to be that manipulative. It could be something as simple as your protagonist cheering up a friend who’s had a bad week. Who doesn’t love someone who’s there for their friends?

There’s a great moment in The Shawshank Redemption where convicted killer and central protagonist, Andy Dufresne, literally risks his life to get his friends a six pack of cold beer on a hot day. Who’s not going to like that person?

Andy Dufresne is an interesting case study for character creation because, if you look at him through a macro lens, he should be boring. He’s quiet. He keeps to himself. He’s introverted, a character-trait that rarely works. Yet he’s one of the most liked characters in movie history. Why?

It’s because my best friend, Stephen King, along with screenwriter, Frank Darabont, put him in sympathetic situations as well as created likable actions. In addition to the famous rooftop beer scene, Andy repeatedly gets abused and even raped by some of the nastier prisoners. Andy always picks himself up after these beatings and keeps going. He doesn’t let it defeat him.

Readers loooooooove that. They love when a character who keeps getting knocked down gets back up and continues to fight.

Andy also sacrifices a week in solitary to provide the prison with the most beautiful song he’s ever heard. Andy spends months of his time helping a young prisoner get his GED.

It’s these ACTIONS that persuade us (some might even say “manipulate us”) to like Andy.

That’s what the amateur screenwriter fails to do. They don’t think about actions. They just think that if they write their character, a character who is often an extension of themselves, a character who has had an enormously interesting life, even if that life only exists in the writer’s mind, that people will like them. But it’s not the case. As manipulative as it sounds, the creation of a likable (or interesting, or compelling) character needs to be constructed.

So stop assuming. Your main character is way too important for you to be assuming readers will root for him. Come up with a plan. You probably want to map out 2-3 moments within the main character’s first five scenes that you can point to and say, “Those moments make my hero likable.”

I’m telling you, this is one of the best “bang for you buck” screenwriting tips you’re ever going to use. Because if you can get good at this, you actually create the opposite effect of what I was talking about at the beginning of this post. We’ll like your main character so much that we’ll still enjoy the script even if we don’t like your story.

Today’s short story receives such a bad rating, I had to revert back to Scriptshadow 1.0 to give it.

Genre: Apocalyptic/Drama

Premise: A college professor is annoyed by the death of a mid-level banker during the end of the world.

About: This is another Stephen King short story sale. It comes from the collection, “If it Bleeds.” It has Darren Aronofsky on board to produce (not direct). Two other stories from the collection have already been purchased. “Rat” by Ben Stiller and “Mr. Harrigan’s Phone” by John Lee Hancock.

Writer: Stephen King

Details: About 120 pages

It used to be that, when you talked about Stephen King, you talked about what a great writer he was. Nowadays, when you talk about King, it’s usually because of some spat he’s having with Elon Musk on Twitter.

It’s kind of sad. But it hasn’t affected his ability to sell his content to Hollywood. Almost every King story that gets written, gets optioned. The man has the Midas touch. Then again, nobody has seen The Life of Chuck Yet. When they do, it could end King’s career…. for good.

Marty is an English professor at a small college in New England. He’s dealing with the deterioration of the internet, which only works sporadically these days. This is because the world’s infrastructure has been falling apart over the last year.

California has fallen into the Pacific Ocean. Florida is, basically, gooey swampland. Food shortages mean that In and Outs are closing down (not in King’s story, just my personal guess). It’s bad, man.

Amongst it all, Marty is mesmerized by the local bank’s billboards and commercials that keep popping up promoting Charles “Chuck” Krantz, who has just retired after giving the bank 39 great years. Or they’re congratulating him for his life and dying at 39 years old. The story is so shabbily written, it’s not clear which of those is the case. But the point is, there are ads everywhere celebrating Chuck Krantz’s contributions and Marty is annoyed by it.

We then find out that Chuck is on a respirator because of a brain tumor. And then he dies. This sends us into Act 2, nine months prior, where an ignorant-to-his-sickness Chuck dances. That’s right. The second act is a dance.

Chuck goes downtown to work, stops in front of some guys playing the drums on the street. He decides to dance. Everyone cheers. Some girl hops in and dances with him. The song ends. They bask in the post-glow excitement. Then they go back to their normal lives.

The final act sends us back even further into Chuck’s life when he was a kid where we basically watch him grow up. We hit all the low-points, like his parents and grand-parents dying – uplifting stuff – before a semi-adult Chuck walks solemnly around the house his grandfather left him. The end.

In an industry that has fully embraced the short story and given out huge monetary rewards for writing these stories, The Life of Chuck has thrown its hat into the ring to win the “worst short story ever” contest.

I’m not exaggerating when I say this may be the worst short story I’ve ever read.

It’s bizarre because you pick up a Stephen King story and you expect to be a) entertained and b) learn something about the craft. A) I was the opposite of entertained. What I went through could better be categorized as torture. And b) The only thing I learned is that Stephen King doesn’t care about writing good stories anymore.

The first act of the story starts off well. The internet is barely working. There’s word that California is falling into the ocean. End-of-the-world scenarios are movie catnip. We moviegoers love them. I love them. So I was intrigued to see where this was going.

Then King leans heavily into, basically, a PSA about the environment. It was as if the story stopped and King, the activist, transported himself in. I remember back when King used to talk about theme in writing. He would write the best story possible then, while rewriting it, he’d search for a theme and place more emphasis on it. These days, he seems to be starting with the theme. His stuff just doesn’t work nearly as well with that approach.

The irony is that the first act was still the best part of the The Life of Chuck. Because at least in the first act, things are happening. The world is falling apart.

The second act is about a middle-aged man dancing. That’s it! That’s what 50 pages are about. A man, Chuck, is walking to work, happens to spot a drummer, starts dancing, is joined by a random younger woman, and they dance while everyone cheers. And that’s the second act!!

If you’re waiting for a point to emerge, get in line. I would not be surprised if King wrote this 120 pages short story in half an hour. Cause there is no fore-thought put into it. There are no setups or payoffs. None of what happens before connects to what happens after. It’s random to the extreme.

Then, the final act – the part of your story that’s supposed to go out with a bang – is just backstory!!!! Long drawn-out boring backstory. Parents died in a car crash (wow, that’s original. I only read about 50 scripts a year that have a car crash backstory). Grandparents die one at a time. And, in between, Chuck sits around so that King can fill us in on whatever other pointless moments in Chuck’s life he can think of.

This is baaaaaad, guys.

I understand that King’s name has weight in the business. But did they read this story??????? Cause this is the worst thing he’s ever written. And you’re going to put it out there for people to see who are going to make fun of you for the next 25 years for it.

Actually, I take that back. This isn’t bad in a fun way where people make fun of it. It’s bad in a sad way. In that way where, the second you finish it, you’ve forgotten it. Nobody will remember this movie for more than three minutes.

There’s this moment in the story where Marty is going to visit his ex-wife, gets to her house at night, then proceeds to notice that every single window in every single house as far down as you can see, all contain a reflection of the “Thanks Chuck” billboard.

It is not explained to us why this happens. It is not explained to us how it happens. It’s as if King’s 10 year old grandson stumbled into the room while he was writing, mumbled, “window reflection” and King just wrote the moment into the book without missing a beat. I cannot emphasize how sloppy and random every choice in this story was.

The only logical reason I can come up with for why they bought this story would be the first act. The first act is all about the world falling apart. California falls into the ocean. The South is a dust bowl. Florida is a swampland. Sinkholes are everywhere. There is no longer enough farmland which means people start starving. Worst of all, the internet stops working.

All of that stuff is very cinematic. So maybe they’ll use that as a jumping-off point for a different story than the one that is told here. Because if they bring in Chuck Krantz, they are signing this movie’s death warrant. Chuck Krantz is the worst character in American history. He will depress you, he will bore you, he will make you never want to read again.

One of the tell-tale signs of bad writing is when the reader stops reading, stares off into space, looks back down at the book, and says to himself, “What is this about?” I must have done that two-dozen times.

Fiction has hit a new low-point. So much so that I’m bringing back a retro rating to rate this script.

[x] Trash

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Backstory is non-story. Part of me thinks King is trolling us by making his climax the least interesting part of any book – backstory. But by putting it on display at such a critical juncture, it highlights just how little payoff backstory provides. Unless you have some sort of extremely unique and interesting backstory or event your main character has gone through that is IMPERATIVE for the reader to know in order for your movie to work, avoid backstory like the plague. Throw it in there in little bits and pieces (Ferris Bueller to Cameron on the phone: “You’ve been saying that since the second grade.”). But, otherwise, avoid it like you would avoid this book.

The daughter of a big-time screenwriter tries her hand at the family business.

Genre: Mystery/Drama

Premise: A documentary crew in contention at the Emmys for their film about wild Alaskan wolves is hiding several big secrets about their troubled 3 month shoot.

About: We’ve got some screenwriting royalty here. Today’s writer, Rose Gilroy, is the daughter of screenwriter Dan Gilroy and the niece of writer Tony Gilroy. I know what you’re thinking Evil Internet People. “She’s an undeserving Nepo Baby! We must banish her to the nine circles of screenwriting hell!” Well, here’s the way we play it down at Scriptshadow: we do not discriminate. We don’t care where you came from, what your skin color is, or what your sexual orientation is. All we care about is: CAN YOU WRITE?? Let’s see if Rose Gilroy can write.

Writer: Rose Gilroy

Details: 95 pages

Rose Gilroy

One of the reasons I chose the logline, “Personal Statement,” (When her family hires an independent admissions consultant to help craft Ivy League-worthy college application essays, a Chinese-American high school student must fight to control her life story and protect her identity) for this weekend’s Logline Showdown was because I’ve been looking for stuff that’s different.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m the first guy who’ll jump on that clever contained thriller premise or a great horror hook. But I see those all the time. My eyes are now more open to unique concepts, even if they don’t bowl me over.

That’s why I chose to review The Pack today. It’s unique. When’s the last time you watched a movie about a documentary awards show? Of course, you still have to build a hook onto that. And the logline provides us that hook in spades. This crew is hiding something about their shoot. Let’s find out what it is.

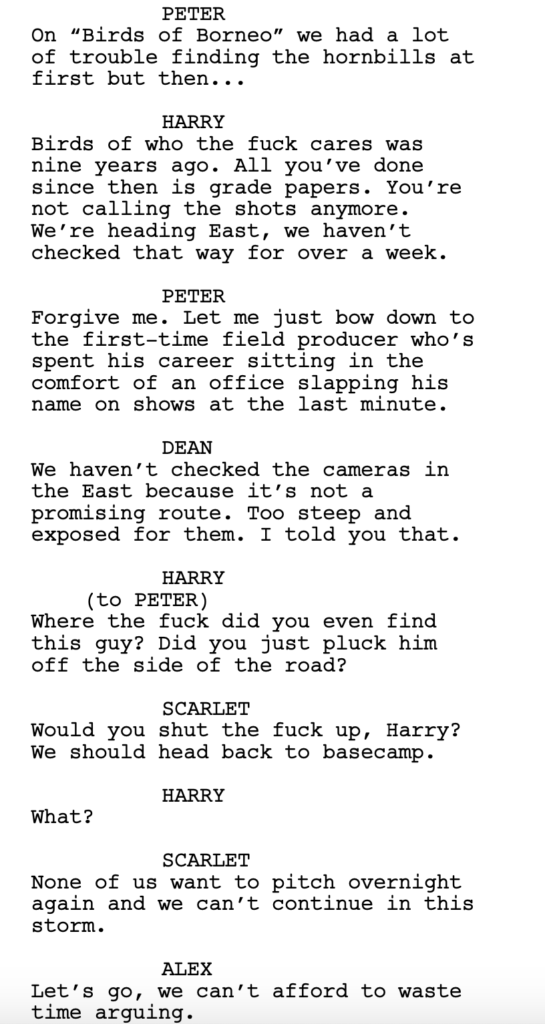

It’s the 39th Annual News and Documentary Emmy Awards and producer Harry Shields has his documentary film, “The Pack,” in contention. Harry is here with his director, Peter, his award-winning cinematographer, Alex, his focus puller, 20-something Scarlet, and his young assistant, Eve.

“The Pack” is about a unique family of wolves up in the Yukon Territory in Alaska. And it was actually Eve, a computer genius, who crunched some numbers to discover that this unique pack of wolves existed. If not for her, they’d have no idea where to go. This tiny team, along with a local tracker, spent several months up in freezing temperatures to document this pack of wolves.

The writer plays with the narrative by bouncing back and forth between the awards show and the crew’s time spent in the Yukon. It’s evident early on that the present-day members of the crew don’t get along, and a lot of that is due to what happened during the production.

So when we go back to Alaska, we’re fed little pieces of the experience which gradually fill in these mystery holes. One of the main problems is that Eve’s calculations were wrong. They spend an entire 6 weeks in the Yukon without seeing a single wolf. And the crew, feeling the pressure of all the money spent on the production, starts leveling their anger towards Eve, who’s so young and inexperienced, she’s emotionally ill-equipped to handle the attacks.

There’s also the question of what happened to the financier of the film. Although he’s alive and well in the Yukon, he’s since passed away by the time of the awards show. This entire situation creates several intriguing questions. What happened to the financier? How did they create an award-winning documentary when it looks like they weren’t able to find any wolves? And what happened to Eve on that trip, who looks like an utterly broken human being at the awards show?

I can now assure everyone: Rose Gilroy is legit.

The cleverness of the way this narrative unfolds – with the cutting back and forth – creates an unpredictable, as well as exciting, read. We’re always champing at the bit to get back to the Yukon so we can learn just a little bit more about what happened back there.

Also, it should be noted that this is not a GSU script. GSU stands for Goal, Stakes, Urgency. There is no goal here. I mean, I guess the goal is to find the wolves. But that’s not what the movie is about. The movie is about what happens to people when they don’t get what they want. When the pressure builds up and you’re stuck in the middle of nowhere with a highly frustrated group.

Instead, the narrative is driven by mystery. While I’ll always champion a high-stakes GOAL as the best way to power a screenplay, a really solid mystery is almost as good. But that’s the key. It has to be a SOLID MYSTERY. It can’t be some dumb generic mystery. That’ll never compete with a goal-driven script.

Which is what I liked most about this. Most mysteries are the same – someone gets murdered and we try to find out whodunnit. That’s like 95% of TV and movie mysteries. So if you can come up with a strong mystery that has nothing to do with that, you’ve got something special. Which is exactly what The Pack is.

You can also see the influence of having an award-winning screenwriter as your guide. This is not a traditional narrative. It’s a parallel narrative. We’re jumping back and forth between time periods. This creates a different rhythm to the story. It provides unique opportunities for plot reveals that you wouldn’t be able to pull off in a sequential story. And it just feels smarter. I know that sounds dumb. But it does.

The Pack also provides us with a great dialogue tip. Which is that your dialogue jumps up several levels whenever you introduce tension. Tension gets people feisty. And when people get feisty, they say way more interesting stuff. That little jab that you’ve been keeping to yourself? When the tension ratchets up, you might not keep that jab to yourself. So you want to introduce tension – naturally of course – whenever you can.

When it comes to mysteries, nothing really matters unless the big reveal is great. But The Pack actually taught me something new about reveals. Because The Pack doesn’t have a show-stopper “Sixth Sense” reveal. The reveal is more character-driven. Which makes it more impactful.

I don’t want to spoil it but, basically, these characters are given a choice at the end. And it’s a choice we kind of saw coming. But because each character has been set up so well, we’re invested in what they’re going to choose to do. And there’s an additional component of, will they all have different choices, or will their choice be made as a “pack?” That’s what makes the ending so strong.

I definitely recommend this. One of the best scripts I’ve read so far this year. It’s a Black List script so it’s out there if you’re looking for it.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Scripts always feel smarter when you can create a metaphor for your characters that matches the subject matter. They’re going out to observe a pack of wolves. But they are, themselves, a pack. And, in the end, they’re more like the wolves than the wolves are.

If I had to guess why Fast and Furious didn’t do boffo numbers this weekend (it came in at 67 million – Fast 7, six years ago, made 150 million its first weekend), I’d venture it’s for the same reason I chose not to see the film myself – It doesn’t look different enough from previous incarnations of the franchise.

In Fast’s defense, it becomes difficult to differentiate yourself when you’ve had nine sequels. But it is doable. When I look back at the Fast franchise, there are three things that have gotten me to watch their films. One: doing something different. I liked the Tokyo Drift angle cause they were trying to do something different from the first two films.

Two, they promoted an action scene that was so amazing, you couldn’t not go. That fuel robbery action scene on moving fuel trucks was one of the coolest action sequences I’ve ever seen in my life. It was also the best edited action scene I’ve ever seen.

And the last thing they do well is stunt casting. They bring in some name that bathes the entire franchise in a new exciting light. That was the case with The Rock. The Rock vs. Vin Diesel? Sign me up!

They went with choice number 3 again this time around but they crapped the bed with their casting. Jason Mamoa. I’ve taken naps more interesting than Jason Mamoa’s performances. Bless Jason. He seems like a genuine guy. But the man does not move any of the needles on the dashboard.

If they want to bring us back for Fast 11, they need to do all three. New fresh concept. Come up with the best action set-piece in the entire franchise. And give us the coolest stunt-casting ever. Maybe a de-aged Jean Claude Van Damme AND a de-aged Steven Seagall? I’m kidding. Or am I? (I’m not)

I’ve been keeping tabs on the Cannes Film Festival. And by keeping tabs, I mean keeping track of how long each standing ovation is. It’s tough to keep up. At one point, a random journalist came back from the bathroom, crossing in front of the audience, and ended up getting an impromptu 3 minute standing ovation.

Indiana Jones got a respectable 5 minute standing ovation but word on the street is that the movie is kind of a mess. Indiana is running up against the same issue Fast and Furious is, which is that you’re attempting to squeeze a new experience out of an old ratty towel.

But you know what? I DON’T CARE. Because it’s Indiana Jones and even though I got burned worse than twice-cooked toast with Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, there’s nothing quite like the Indiana Jones experience. I’m doing my best to avoid spoilers and I’m hoping that the de-aged Indiana Jones stuff figures out a way to get us some vintage Indiana.

On Saturday night, Killers of the Flower Moon got a NINE MINUTE standing ovation, a full six minutes more than Bathroom Guy. I’m bit a torn about this movie. As you remember, I loved the book. LOVED IT. It was so freaking good. And the trailer they just released? A-PLUS. Stunning. Best trailer all year. Maybe even the best in the last five years.

But listening to the press conferences of the movie, it seems like they’ve made a major change to the book. The story of the Osage is, no doubt, sad. But what balanced out that sadness was the investigation into who was doing the killing of these Osage members. The author had built this procedural element into the mix, which had us curiously turning the pages. And that made it exciting.

But, apparently, Scorsese took that out. Which has turned the movie into one giant sad-fest. Maybe even a moralizing sad-fest. If their plan here is to make people feel bad for things other people did 150 years ago? I don’t want to be rude but go walk barefoot in a room full of loose legos.

Sure, if you go that route, it gets you standing ovations and pats on the back from people within the industry, not to mention those back pats you’re giving yourself. But it leaves audiences feeling cold. No actual moviegoers want to see a movie designed to make them feel bad about themselves.

What I’m hoping is that this is just the media doing its media thing. They have to play up these narratives cause it makes them feel good about themselves. But the reality is, we moviegoers just want a good movie. That’s it! We don’t want to be preached to. So, hopefully, that’s what this movie is. Because I’m rooting for this film. I want it to be great. It’s such an interesting story. And I’m a sucker for a great ironic premise, which is exactly what this is.

I have a feeling it’s going to be a neck-and-neck Oscar battle between this and Oppenheimer. I can’t wait to see who wins.

Okay! I’m going to finish up with a quick script-to-screen breakdown of “Air.”

I LOVED the “Air” script. It made my top 25. What made the script so good was that it FLEW BY. It had a great underdog main character whose relentless determination gave the story incomparable momentum. You both loved Sonny Vaccaro and were swept up by his pursuit of Michael Jeffrey Jordan (whose face is never seen in the script or film – love it!).

For these reasons, I was more than excited to see what it looked like in movie form. I knew that, if it hit on all cylinders, it had the potential to be the next Jerry Maguire.

I probably shouldn’t have placed those expectations on it. No, the movie isn’t bad. But it’s not nearly as good as the script. And there is one big reason for that: It doesn’t look like a movie.

It looks like a student film.

I’m sorry but it does. This is Ben Affleck’s worst directing effort to date. And while Matt Damon may not have phoned it in, he occasionally barks it in from the other room.

The entire movie feels like it was done via a series of second takes. Not a single scene feels thought-through or lived in. You could practically hear the A.D. saying, “We’re running out of time. We gotta keep moving. You only get two takes for this setup!”

Matt Damon is giving us these perfunctory performances where you can sense that he hasn’t fully memorized his lines. Compare his acting in this movie to Good Will Hunting where you could tell he’d tried EVERY SINGLE ANGLE in every one of those scenes so he knew what worked best by the time the camera was rolling. Not even remotely the case here.

And where is the money? Show it to me!

Where’s the money on the screen?? That’s one of the ways you can tell a good director. They can make a movie look amazing for way less money than they wanted. This film is the opposite! It cost 90 million dollars! Yet it looks like a 15 million dollar film!!! They shot it in a bunch of rooms! I could’ve done that.

The one set they built – Nike headquarters – is dark, boring, and empty. Where are the people??? Could you not afford extras? Compare that to the agency set in Jerry Maguire. You could feel the life in that set. Here, it looks like they turned half the lights off to save money.

You may say, Carson, the money is in Matt Damon and Ben Affleck! They’re movie stars. You gotta pay for that. Sorry: BUT NO! This is Matt and Ben’s first movie for their new production company. They shouldn’t be getting paid anything. They should be putting every single dollar on screen.

I cannot emphasize how lifelessly this was directed. It was as if they went to each actor’s home and did close-ups and had them read lines and then stitched the performances together via clever editing. Go watch this film. It’s 90% talking heads in dark rooms. What is this? A 1970s TV show??? Where did the money go???? 90 million dollars!?? Robert Rodriquez made a better looking film for 7000 dollars!!!

I’m baffled.

But you know what? This shows the power of a great script. The movie survived this dreadful display of directing solely because of how good the script was. Even with Matt Damon getting his lines phoned in through an earpiece, the dialogue was still good. His character’s desire to sign Michael Jordan kept us engaged.

But it never ceases to amaze me how a director’s interpretation of a script can screw up what the original author had in mind. The directing here needed a shot of adrenaline. Ben Affleck is a good director. He won an Oscar! Which is why I will never understand what he was thinking with this one.