Genre: Legal Drama (True Story)

Premise: The life of a cynical San Francisco criminal lawyer at the top of his career unravels when he agrees to represent a father accused of killing his infant son in an extraordinary case that challenges widely accepted medical beliefs, a biased justice system, and his own personal worldview. Based on true events.

About: This is the second script in last year’s Black List that has three writers on it! The first was the script written by the Murder Ink trio, which I liked. These writers have begun to make some minor inroads into the industry. Nathan Gabaeff has a movie he wrote and directed called Avenge the Crows. His brother Isaac wrote a TV episode. But making the Black List appears to be their big break.

Writers: Thomas Berry, Isaac Gabaeff, and Nathan Gabaeff

Details: 121 pages

Carrell for Conlon?

Carrell for Conlon?

If it’s taken me this long to review a Black List script, it typically means there’s something I find questionable about the concept. With False Truth, the concept seems to be both too small and too misguided. Let me explain. The idea is small in that it could be a Good Wife episode. Courtroom thrillers used to be common until legal TV dramas pillaged all their scenarios.

This makes almost every courtroom concept today a TV episode in the audience’s minds. Back in the day, John Grisham was able to find a few big flashy legal cases that felt like movies. But, since then, we’ve had a few thousand television courtroom cases, so it’s super rare to find one that’s worthy of a movie canvas.

The other problem I have is that there’s no winning when the subject matter is a baby’s death. If the father wins the case, so what? His baby doesn’t come back to life. So all of us still lose. Can a concept get more depressing?

I was confused as to why anyone would want to write a movie about this until I got to page 28. That’s when I read this line: “But if it’s a shaken baby case there’s one guy you really want to get… Doctor Steven Gabaeff.” Gabaeff? Where have I seen that name before? It took me a moment but then I realized, wait a minute, this is the writer’s last name!

So, obviously, the writers knew someone – I’m guessing it’s their dad – who was involved in this case and because they have such intimate knowledge accessible to them about the case, they said, “We should write a movie about this.” The fact that the writers did have that connection made me more intrigued. But I still think it’s a tough sell with a concept like this. Let’s see if I’m wrong.

Jennie gets the worst call imaginable from her husband, Kristian, who’s just told her that their infant son is in the hospital because he dropped him. She races to the hospital where she gets updated. Her son is now in a coma (he eventually dies) and the doctors suspect that Kristian has attempted to kill his son with something called “Shaken Baby Syndrome.”

This is when you shake a baby too fast. Kristian is quickly carted off to jail and Jennie hires noted San Francisco attorney Elliot Conlon, a man who used to stand for things but now seems content with making a lot of money, no matter who the defendant is. That’s going to be pushed to the limit since he’s now defending a potential child murderer.

Conlon digs deep into the science of Shaken Baby Syndrome and learns that they have the nastiest lobbyists in the world. These people make sure that every person who gets accused of this spends the rest of their life in prison. Conlon’s also been dealt a bad defendant, as Kristian is big and emotionless. He’s immediately compared to Lennie Small from In Mice and Men.

As we race towards the court case, Conlon finds out that the whole Shaken Baby world is a lie. That the science doesn’t hold water. In fact (spoiler), he learns that the medical community and legal community know this but that they’ve convicted so many people of it by this point that there’s no going back. They have to keep reinforcing the lie. Luckily, Conlon puts enough fear into the establishment that Kristian is inevitably let go.

There are a couple of approaches you can take to a story like this. You can create doubt about the suspect and then take your reader on a roller-coaster ride where sometimes you make the suspect look innocent and sometimes you make them look guilty, and the reader is constantly trying to solve that puzzle.

This is the approach they take in docs (or series) like The Staircase. At first we think the husband definitely did it. Then, when we hear him talk, he doesn’t sound like he did it at all. Then, a little later, we learn that he was having affairs. Now we think he did it again. But then we’re told that the wife knew about the affairs. Then we hear another woman he knew died from a staircase fall and we’re back on the “guilty” train again. These can be fun when executed well.

The other approach you can take is the one they took in this script. Which is that the father is clearly innocent but everyone in the world thinks he’s a child-killer and they’re determined to make sure he’s convicted as so. This creates an enormous amount of sympathy from the reader because nobody wants to see something bad happen to someone who’s clearly innocent. Even less so if everyone wants to take him down in bad faith.

For that reason, the script worked for me, which I was surprised by. I mean, yes, I still think a script like this is a losing proposition cause it’s so depressing. But I was into the stuff where they’re trying to take down Kristian. I wanted him to overcome their full-force attack.

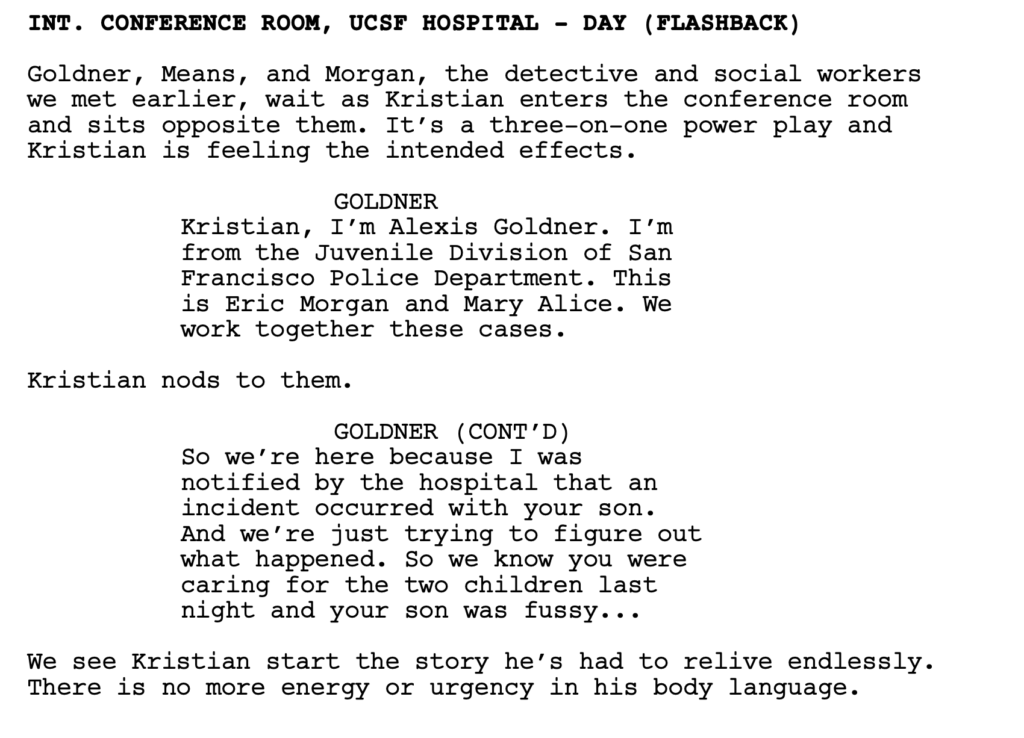

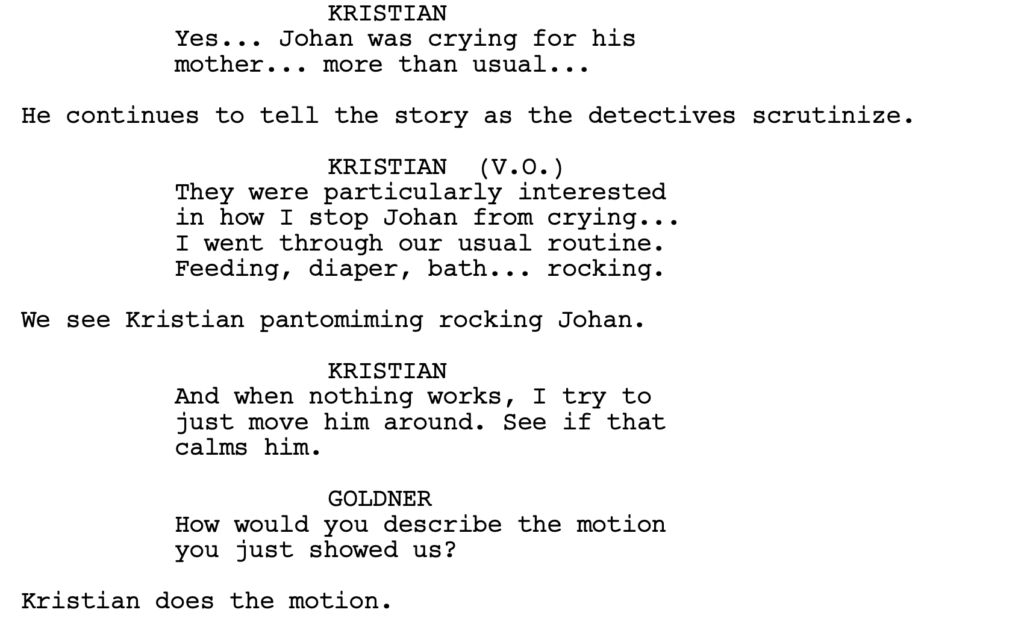

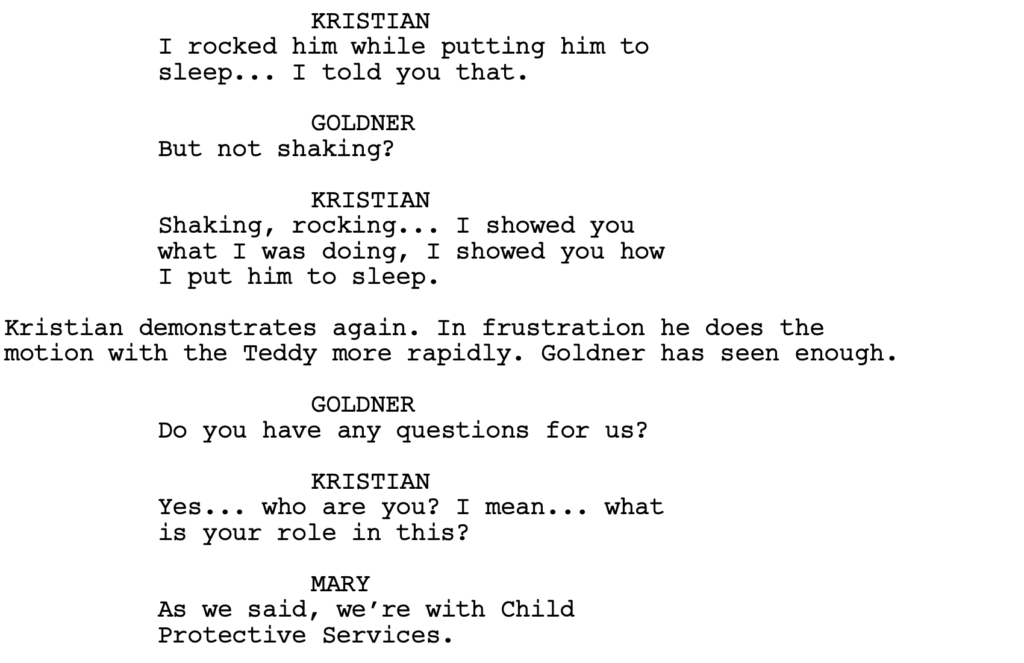

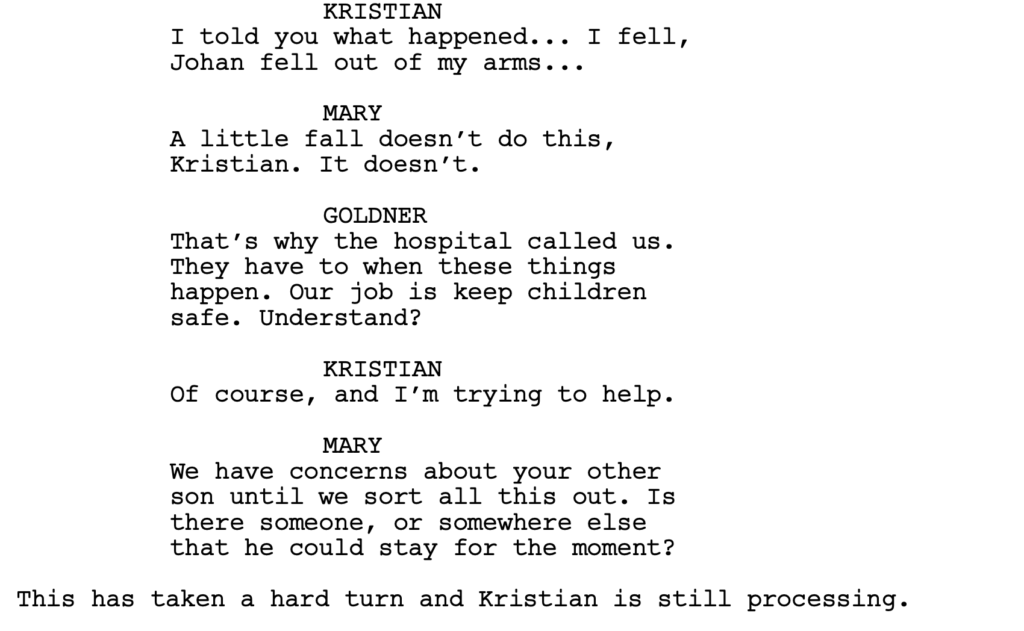

Which is a perfect segue into today’s dialogue lesson. The following scene is a long one. But it’s also a great example of how you can write good dialogue without being a wordsmith. If you’re good at setting up the right scenario, the scenario will do the work for you. I think most of you could write this scene yourselves if it was set up for you. Whereas, with a Tarantino scene, maybe .001% of you could write something similar. In other words dialogue scenes like this are within reach.

The scene takes place with Kristian being brought in to see Child Services not long after he and his comatose child arrive at the hospital.

You want to note a couple of key things here. One, the child services characters have the goal in the scene. It’s to find out what led to the kid’s injury. However, here’s where our nifty dialogue lesson comes into play. The child services people are framing the conversation as if that’s the goal. But what they’re really trying to do is get Kristian to admit he killed his kid.

Dialogue always plays better when there’s something going on on the surface, as well as something that’s going on underneath the surface, which is clearly happening here.

Also, note the extremely high stakes of the scene. If Kristian screws up and says the wrong thing, he doesn’t get a pass. That thing very well could be the smoking gun the prosecution uses to convict him of murder in court. Dialogue is electric when the stakes are high.

Another thing is that the child services people are being disingenuous. They’re trying to trick him – pretending they’re on his side when they’re the exact opposite. What this does is it makes the reader protective of Kristian. We feel like he’s being misled, so we become his ally in the scene. We’re rooting for him to survive.

Finally, note the conflict. Almost every good dialogue scene has some level of conflict in it. And what creates more conflict than one side trying to ruin a guy’s life and the other side hanging on for dear life?

By the way, the reason this doesn’t have to be Tarantino-type dialogue is because the content of the scene is so strong. There are real consequences to this moment. And when that’s the case, you don’t need to prove your verbal jousting skills. Those will actually make the scene worse.

Once you’re able to consistently write a scene like this, you’re going to be okay dialogue-wise. Cause these scenes can really carry a script. Just note that a lot of the work here was done before the scene, not in the scene. Once the scene is set up, the dialogue writes itself.

I’m still not thrilled that the overall feeling I get from this script is one of depression. I like to either feel good at the end of a script or, at the very least, I want it to make me think. With that said, the script surprised me by how much it pulled me in. So I think it’s worth checking out.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: It helps in these scripts when the case is about something bigger than just winning the case. While False Truth isn’t making a point about racism or anything gigantic like that, it is about the fact that these “shaking baby” cases are bogus and that evil overly-emotional people have been using their influence to convict a lot of innocent people through pseudo-science. So we do get the sense that the court victory has a bigger effect on the world.

Genre: Romantic Comedy

Premise: With the future of Manhattan’s Chinatown at stake, a stubborn store clerk battles against an innovative CEO’s expansion plan, while both are unaware they’ve been falling in love with each other on a new, anonymous dating app.

About: This script finished on last year’s Black List. William Yu has written a couple of short films, one of which he directed.

Writer: William Yu

Details: 117 pages (!!)

I don’t know who this is but she should star in this movie

I don’t know who this is but she should star in this movie

*****WE INTERRUPT THIS REGULARLY SCHEDULED PROGRAM*****

With White Lotus doing so well at the Emmys, I wanted to remind you of the ENTIRE WEEK I once took to praise this amaaaaaaaazing series. Here ya go!!!

Day 1

Day 2

Day 3

Day 4

Day 5

*****NOW BACK TO TODAY’S REVIEW****

As we continue this theme of ‘what makes good dialogue’ that I will loosely continue over the next few weeks in the lead up to the Scriptshadow Dialogue Book, I thought it’d fun to review a romantic comedy, a genre that is designed to showcase dialogue. I figured, good or bad, we could learn a thing or two about dialogue today. So let’s jump to it!

We’re in Chinatown, New York City. Sophia Chao is so focused on her “WeWork” like startup company that she hasn’t had a lot of success dating. Hence, she says “screw you guys, I’m outta here” (no, she didn’t really say this) and focuses on convincing three elderly store owners to sell to her so she can start building her “OpenSpace” headquarters.

The grandson of one of these owners is Brandon Wong. Brandon is Chinese-American and very adamant that big corporations are bad! Very bad! He spends a lot of time protesting and protecting the traditions of his hometown. When he learns that Sophia is trying to build a company on his street, he takes his protesting to the next level.

Now since both characters are sick of the dating scene, they start using a new anonymous dating app. No pictures. Just an algorithm that matches you up. In case you were wondering, Brandon and Sophia match and start chatting on the app. They don’t want to go on dates. They just want to chat on the app. And start falling for each other.

Then Brandon gets some bad news. His grandma actually wants to sell the store and move to Florida! If she does this, Big Bad Sophia will win and Brandon can’t have that. So Brandon makes his grandma promise to give him the summer to drum up business and start making some real money for the store. She reluctantly agrees and Brandon is off to the races, all while occasionally bumping into Sophia and having no idea she’s his online girlfriend.

Let me start off by saying the hoops we have to jump through to buy into this story are so high, they require the latest Air Jordans to reach. The writer needed a way to have these two date each other without knowing who the other was, so he set up an anonymous dating app with no pictures and then, even after they start dating, they don’t want to see each other, which, of course, is necessary, since the second they see each other, the plot doesn’t work anymore. It pummels the suspension of disbelief into submission.

I will say that I liked the choice to make the guy the local business owner and the girl the big mean CEO. That was different from what I’m used to seeing. But outside of that, I struggled to find things to celebrate here.

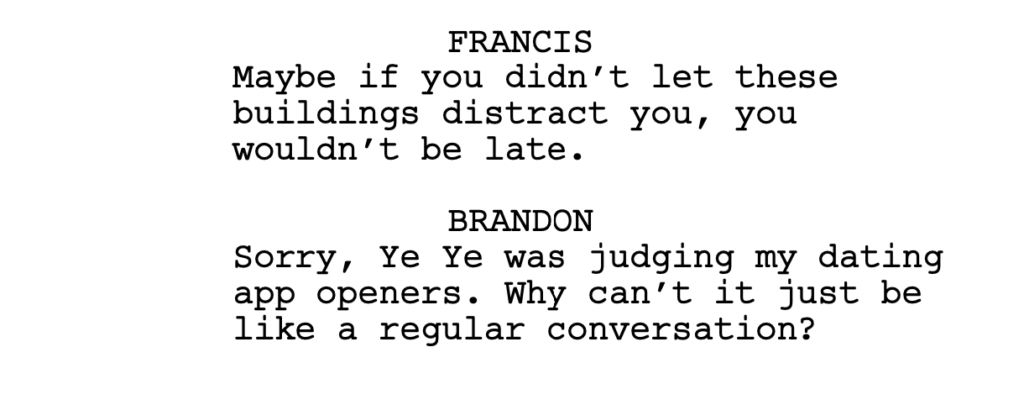

Let’s get to the dialogue cause that’s our focus these days. Here’s any early exchange where Brandon and Francis meet at a protest and debate the challenges of dating in the modern era. Brandon doesn’t do a lot of dating, which Francis takes exception with.

Okay so we start out with an analogy. And in my dialogue studies, I’ve realized that analogies can be a big asset in sprucing up dialogue. Everyone likes a good analogy. But here’s the rub. It’s gotta be a good one. And this one is okay, I guess. Comparing dating to war is something I’ve heard before so it’s not exactly a fresh take on the topic, which you would prefer your analogy to be. But it’s an okay start.

From there, we cover a little backstory. We introduce some character information, as we’re learning about Brandon’s dating past. But then we run into, “No one’s perfect.” This is such a boring common phrase that it generic-izes the conversation. When characters say generic things, we start seeing the dialogue as generic.

Even though I didn’t love the war stuff, the writer probably should’ve continued on with that analogy. Keep using the war stuff to explain their thoughts and ideas about dating. You introduced it. You might as well keep using it.

We then come to Francis’s strategy on dating. Francis is clearly the comedic relief in the film. For that reason, you need him to be funny. I know that sounds obvious but what I mean is: chuckle-worthy isn’t enough. He has to be legitimately funny. And here, he uses this Target line, which I like in that it’s SPECIFIC. He didn’t say something generic like, “I just give’m a taste of that Francis charm.”

But the joke has to have some logical setup and payoff to it that we understand and therefore laugh at. I’m not sure this has that. I suppose it’s kind of funny that he takes them to these random places. But then we get the line, “West Elm is too far, you’re not a sociopath.” Assuming we’re on board with the running home decor joke, what does one of these places being too far away have to do with being a sociopath?

It’s that “bridge too far” thing that we all struggle with as writers. The joke makes sense in our head because we can see the 5 other dots we’ve connected to get to the punchline. The reader can’t see those other dots, though. They see the first (home decor date) and the last (sociopath for stores that are too far away) and can’t make the connection.

Now you have to understand, the script I read right before this – for my dialogue book – was the Fleabag pilot. And Waller-Bridge’s jokes are so light-years ahead of everything that it was a bit like listening to Chopin and then Justin Bieber. I mean look at the difference here…

The scenario itself is so much more clever and unique. Who starts masturbating to a political figure’s speech? But it wasn’t just that. The boyfriend’s reaction clearly informs us that this has been an ongoing problem, which makes the interaction even funnier. And then we watch as she desperately squirms to try and save herself, which is always fun to watch. All of this is made even funnier by the fact that the previous scene has her meeting a guy, the guy asking if she has a boyfriend, and when she tells him, no, they just broke up, the guy assumes that the guy is the one who screwed it up. We then immediately cut to the above scene.

Anyway, getting back to It Was You.

The last line is Brandon asking Francis if his dating strategy works and Francis saying, “No it doesn’t, and I don’t know why.” An obvious punchline like this isn’t very funny because it’s not at all surprising. Francis informing us that a lousy dating tactic has lousy results is… expected, right? So where’s the joke? It would’ve been funnier if he’d told us that a lousy dating strategy actually worked great! So a line like, “Believe it or not, my success rate is about 80%.” Cause we’re not expecting that.

This is what’s hard about writing dialogue. We all think different stuff is good. We all think different stuff is funny. But one of my simplest criteria for objectively analyzing dialogue is, “Could this scene have been conceived of and written in ten minutes?” If so, the writer isn’t doing enough. This scene definitely feels like that.

You have to get into the reader’s head and ask what they’re expecting from this dialogue and try to outsmart them or keep coming back to the scene and trying to one-up the jokes in it. “Is this the funniest line I can use here? Is there something better?” Every rewrite, keep trying to top yourself with the jokes.

So why was that Fleabag scene so unique? How can you pull that off as a writer? I suspect that one of Waller-Bridge’s friends shamefully admitted to her, on a night out drinking, that she masturbated to the Prime Minister on TV once. And Waller-Bridge took that idea and said, what if the Fleabag character not only did that, but it was an ongoing problem in her relationship?

That’s how you build the framework for original funny situations. The problem most writers make is that they’re drawing from movies that they’ve seen instead of real life. So they’re just rewriting scenes that have already been written, which is definitely what this scene from It Was You felt like.

Unfortunately, I’ve run out of time to judge the rest of the script but I think it’s safe to say that you can guess what happens. There are a few fun scenes when the two ignorantly run into each other in real life. But the script can never overcome the amount of buy-in it’s asking for. I just couldn’t get past the anonymous dating app thing. Name me one person in the world, who isn’t blind, that uses dating apps without pictures.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Every time you write a scene of dialogue, I want you to imagine that dialogue posted here, on this site, in the cold naked light of day. Would it hold up? Are you mentally making excuses for it? If so, time to rewrite that dialogue, baby.

As I continue to work on the Scriptshadow dialogue book, aka the greatest book on dialogue ever written (and it’s not even close), I’ve noticed that when you watch film and TV solely to analyze dialogue, you see things you wouldn’t normally pick up on.

For example, I forgot how plot-centric all the dialogue in Hollywood movies was. I knew it was a lot. But virtually 90% of the dialogue scenes are used to explain where we are in the plot or what needs to happen next. And those scenes are very short. I watched Spiderman: Homecoming again and I think there were five dialogue scenes that were longer than 2 minutes. It was crazy.

Meanwhile, you have television, which, because the plot isn’t as important, and because there’s a lot less urgency, the dialogue scenes end up lasting a lot longer. Now, of course, I always knew this. But I didn’t realize how pronounced it was until I compared movie and TV dialogue so closely.

Needless to say, it’s been illuminating and I can’t wait to share all my findings with you.

In the meantime, we have to entertain ourselves not with movies, since nothing came out this weekend, but TV, which is where all the action is at. Tomorrow night we’ve got the Emmys. Go White Lotus. Cobra Kai just dropped a new season on Netflix. The only person they haven’t brought back yet is Mr. Miagi so maybe he’ll turn up this year. Lord of the Rings apparently didn’t give up after its first two episodes and premiered a third one this weekend. I appreciate that they’re continuing to try. House of the Dragon episode 4 comes out tonight (Sunday)! It’s definitely a TV universe we’re living in.

The Disney Expo also debuted some fresh TV news with a new trailer for the stellar looking, “Willow.” That show is coming out of nowhere and I love it. I’m also a bit confused why Warwick Davis hasn’t aged at all considering he was born in the 20s. They gave us a new Andor trailer, which was accompanied by that cool little Star Wars flute score. And, by golly, we’ve got a new Mandalorian trailer, which was easily the highlight of the expo due to the return of… BABU-FREAKING-FRICK!

Maybe Lucasfilm reads Scriptshadow because I said after Episode 9 that if Baby Yoda and Babu Frick ever met, political division would subside, countries would voluntarily destroy their nuclear arsenals, chupacabras would fly around on unicorns, and there’d be world peace for 500 years. Well, folks, it looks like that’s going to happen cause I saw Baby Yoda in this trailer and I saw Babu Frick in this trailer and since I know that Star Wars would NEVER imply such a divine meeting and not show us said meeting, that wondrous Star Wars moment which we shall all need a week of rest from afterwards in order to recuperate, will happen. And, to me, that’s the only episode they need to air and I’ll be happy. Actually, just air that scene and I’ll be happy. A 90 second season and I’m a Star Wars fan again.

The exact opposite of Baby Yoda Babu Frick cuteness would be the upcoming Andor, whose latest trailer seems determined to frighten away anybody under the age of 55. “Fun” is not in the Sabacc cards for this Star Wars show as our showrunner, the only showrunner in history who openly despises the show he’s making, attempts to give us something so serious, it makes Manchester By The Sea look like Jumanji. I mean, I’m going to watch this show. But every trailer has been woven through a “No Fun For You” app, where as soon as a happy moment is detected, it is destroyed with extreme prejudice. I think people *think* they want a serious Star Wars show. But they may be surprised at what Star Wars looks like without fun.

Another big announcement was the Marvel “Secret Invasion” trailer which is a quasi sequel to Captain Marvel and follows Samuel Jackson’s Nick Fury as he navigates an alien invasion that’s secretly happening under mankind’s nose. This was originally supposed to be a movie and the fact that they turned it into a TV show tells me that Marvel isn’t so hot on giving Nick Fury his own movie. Which they probably shouldn’t. I’m surprised they’ve gotten as much mileage out of the character as they have. But, in his current state, they may as well nickname him, “Nick Furgettable.” At least the show has Ben Mendelsohn. He’ll be fun. But I think the only invasion that’s going to happen with this show is of the low ratings variety.

D23 did have some film news. Unfortunately, they didn’t show as anything we really wanted to see, like the Indiana Jones 5 trailer or the Avatar footage (is anyone as confused as I am that Avatar 2 is coming out in December and all we’ve seen is a teaser?). I know that everyone was highly expecting the Fantastic Four cast to be announced but I get the sense that Feige wants to take his time with FF4 because nobody’s ever been able to figure it out. I mean, the last version of it had four of the hottest young actors in Hollywood at the time, along with one of the buzziest directors. And it turned into a disaster. So there’s something about this franchise that isn’t easy to crack. And kudos to Feige for taking his time and figuring it out.

We got to see the Little Mermaid trailer, finally. It honestly looks better than I thought it was going to. This is easily the most difficult “live-action” adaptation Disney has done of its animated classics. I’m not bothered by them changing Ariel’s ethnicity. The spirt of the character seems to have been captured and that’s what’s most important. I do think it’s weird that these live-action movies are all animated though. You’re animating your animated movies. Like, whoa, dude. Do we even live in life anymore?

The most surprising announcement was the lineup for the Marvel Thunderbolts movie. For those who don’t know, Thunderbolts is Marvel’s answer to The Suicide Squad. They’re the bad guys who are going to come together and be good for a little bit. The team is being led by the new Black Widow, played by Florence Pugh, which I think is a great choice. It’s got her brother, Red Guardian, played by David Harbour, another character I like. From there, things get wonky.

You’ve got Taskmaster, who was a fairly cool character from Black Widow with some neat fighting scenes. You’ve got Winter Soldier, who continues to be one of the most uninteresting superheroes ever. I don’t know why he continues to show up in the Marvel universe. You’ve got Ghost, who was that awful villain from Ant-Man 2. The real team-up in that movie was her and Wasp. Unfortunately, their goal was to destroy the Ant-Man franchise. Then you have US Agent, who I don’t even understand. I guess he’s a Captain America knock-off?

As you can see, the movie doesn’t have a stand-out superhero. Its best character is probably Black Widow 2 and she’s barely had any time in the Marvel Universe. So it’s asking a lot for her to lead the charge. It’s not too late to add some star power, Mr. Feige. I’d like to see Venom in there. I’d love to see Deadpool. Gimme some Wolverine. Grey Hulk. Daredevil. Moon Knight. In other words, some characters who could actually add legitimacy to the franchise. This all feels very “B-Team” at the moment.

Finally, the Oscar season is beginning, which means you’re going to start seeing big campaigns pop up and hear things like, “The film that got a four-hour standing ovation at the Icelandic Film Festival.” It can be hard to see through the marketing fog. But I’d personally look out for The Whale and The Menu, two scripts I loved. Steven Spielberg’s autobiographical movie, The Fabelmans, seems to have had a nice debut at Toronto. There’s another Knives Out movie for Star Wars destroyer, Rian Johnson, which I’m sure some will enjoy. And there’s the star-powered Babylon, from La La Land director, Damien Chazelle. We’re going to be seeing all those movies as the year wraps up. By the way, every one of those films is going to be dialogue-friendly.

Which reminds me, the hardest thing about dialogue – and something I’ve seen you guys discussing in the comments – is the aspect I’m tentatively titling, “the verbal arena.” It’s that aspect of dialogue that feels unteachable. It’s Fleabag’s unique take on late night hook-ups. It’s Juno’s colorful vocabulary. It’s Pulp Fiction’s roundabout playfullness. It’s where creative dialogue really comes from. I’m curious what you guys think is the secret to “the verbal arena.” Is there a way, in your opinion, to learn that? If so, what are your methods for doing so?

Spoiler alert: I think everyone can get better at it. But I’m curious to hear what you guys think.

I’ve been working hard on my dialogue book.

One of the most frustrating things about writing the book has been finding recent movies with good dialogue to reference! Most great feature film dialogue went out the window in the early 2000s with the death of the indie film. If any of you have suggestions for good dialogue movies post-2015, I’d love to hear them in the comments.

For this reason, I decided to go in the opposite direction and throw in one of the most famous dialogue movies of all time and one I’m not intimately familiar with – Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf. I think I even did an article about this movie years ago but I don’t remember a lot from the film other than the characters all seemed very angry.

Rewatching it was strange because I’ve been writing all of these dialogue tips in my book, believing they were inarguable, only to realize after Virginia Woolf, that there’s more to this dialogue thing than meets the eye.

A rule I was absolutely certain of was that, going into a scene, at least one character needed to have a goal. I didn’t think dialogue could survive without that. Because, otherwise, people are just talking to fill in the space. There’s no purpose to what they’re saying.

Well, with Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, which is about an aging couple who works at a prestigious university and a young couple who come by for some late-night socializing – I realized that this divine dialogue truth wasn’t as universal as I thought.

The characters here would often speak without a clear goal, and for long periods of time. In fact, there were even moments where characters only spoke to break the silence. I mean I guess you can say that “breaking the silence” is a goal, so maybe my precious rule is still in tact. But I didn’t think that a scene could survive when the goal was that weak.

As I continued to watch the movie, I realized that there was one dialogue truth that is always present – and that is CONFLICT.

This whole movie is slathered in conflict. There isn’t a single frame that doesn’t have it. So even though the characters are not always speaking with purpose, the dialogue is still entertaining due to the fact that conflict is present.

And it’s conflict on multiple levels, which I think is the reason it’s able to be so good in spite of its lack of clear goals. If you’re doubling up on conflict, that extra dose could be the substitute you need for a goal-less scene.

What do you mean “doubling up,” Carson?

For starters, the central married couple, Martha and George, hate each other. She hates him because he’s not enough of a man (by the way, this is the first fictional story I know of that implores the insult, “Simp”). And he hates her because she’s constantly cruel to him (not to mention, her college president father’s superior presence always hangs over him).

This creates the undercurrent of tension in every scene. It is, what most people refer to as, “subtext.” Even without saying anything, they’re already saying stuff.

Then this young couple comes along with their perfect young bodies and whole life in front of them and it just sets George off. He uses them, then, to spit out various levels of provocation and frustration. That’s where the second level of conflict is occurring – on the surface.

This doubling down ensures that every line of dialogue has bite to it. Here’s a scene from early on in the movie where Nick, the young professor, is starting to get prickly in response to George’s aggression…

I think the issue I’m grappling with here is that while there isn’t an obvious purpose to George’s interaction with Nick – George is not, for example, trying to get Nick to invest in a business venture of his – I’m wondering if there’s some directive to this conversation that can be quantified, and therefore taught.

George is obviously riling Nick up. That is his internal “goal” in the moment. But why? And is it something that I should be teaching writers to do? Have their characters start sh@# with other characters for no reason. Yes, you get conflict-heavy dialogue. But it’s without structure, without a point.

I think that Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf pushes up against that older belief that movie dialogue should mirror real-life dialogue. In real life, people are mean to other people because they hate themselves or hate their life and they’re just stirring the pot to stir it. They don’t have some divine goal in the moment other than to spew out their thoughts and hurt someone else.

Even as I’m writing that, I go back to this idea of: well, maybe all good dialogue does have a goal, then. Because isn’t trying to hurt someone with your words a goal?

In digging a little deeper, I noticed that while there isn’t some big goal George is trying to achieve, he is a LEADER. He is pushing the scene forward. And that’s worth bringing attention to. Because maybe the real baseline to good dialogue is that someone is pushing the scene forward. George is a force here. He is trying to agitate and aggravate Nick. We’re then curious to see if Nick will crack or fight back. Maybe that’s enough.

What you don’t want in a scene is two characters who are passive. The only thing worse than one character who tries to stir sh#@ up for no reason is zero characters who try to stir sh@# up for no reason because then the scene is lifeless.

Another complication to figuring out this odd movie is that it was originally a play. In plays, you have to fill up 90 minutes of talking somehow. Movies are more visual, which allows you to do more showing than telling. So is this just a case of a playwright filling up space with dialogue cause he has to? Dialogue that wouldn’t normally be in a movie?

I’m going to keep working on this because it’s my belief that the best dialogue has purpose. And that purpose comes from a character who has some sort of goal or “want” in the scene. I may have to dig deeper into Virginia Woolf to see if the film is, indeed, achieving this and I’m just missing it, or if there are deeper secrets yet for me to learn about dialogue.

In the meantime, feel free to provide your own thoughts on this movie, your own suggestions on good dialogue movies post-2015 from screenwriters not named Tarantino (I’ve got enough of him in the book). Share your own dialogue tips. And leave suggestions on what aspects of dialogue you want explored in the book. Feel free to share your dialogue struggles as well. The more I know about what perplexes you guys, the better I can make the book.

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf is on HBO Max.

$50 OFF A SCRIPTSHADOW SCREENPLAY CONSULTATION! – The Labor Day deal may be over but you can still save some money on a script consultation! I have a 4 page notes package or a more detailed 8 page option designed to both fix your script and improve your writing. I also give feedback on loglines (just $25!), outlines, synopses, first acts, or any aspect of screenwriting you need help with. This includes Zoom calls discussing anything from talking through your script to getting advice on how to break into the industry. If you’re interested, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and let’s set something up!

Genre: Drama

Premise: After a woman becomes one of the first female presidents of a 1950s publishing house in New York, she draws a former college classmate into her orbit, who soon finds her literary empire is not what it appears to be.

About: This script finished on last year’s Black List. The writer, Laura Kosann, has one feature film credit, called The Social Ones, about social media influencers. She also won the Nicholl Screenwriting Contest, with her script, The Ideal Woman, about a housewife indirectly involved in the Cuban Missile Crisis. In a flashpoint of serendipity, connecting today’s script with popular culture, you can watch a conversation Kosann has with Olivia Wilde about that screenplay here.

Writer: Laura Kosann

Details: 111 pages

Haley Lu Richardson for Helena?

Haley Lu Richardson for Helena?

A strange thing has been happening. All the Black List scripts I’ve been avoiding are ending up being better than the scripts that I actually wanted to read from the list! What does this mean? Does it mean loglines are worthless? Does it mean ideas don’t mean anything?? That only the content matters? Does it mean I’ve been woke this whole time and didn’t even know it? So many questions. So few answers.

Today’s script is an interesting one because it’s spotlighting this strange funk we’re in as a screenwriting community where we’re all sort of brainwashed into writing the same stuff. Whenever you’re pushed towards writing a certain way, you’re not being true to yourself. And when you take yourself out of the equation, it’s impossible for your writing to stand out. Your point of view is what makes your writing individualistic.

Now today’s script may very well be true to Kosann. I’m not saying it isn’t. I just know that I read every script in town. And anything that deals with social issues in the 2020s is written one way and one way only. That may make sense to you on a personal level. It may line up with your beliefs. But I can promise you, it’s making you a worse storyteller. Cause if I can predict what you’re going to write on page 80 after only reading your first 5 pages, you’re allowing your personal beliefs to sabotage your ability to surprise the reader.

When all is said and done, I’m happy with where Kosann took this script. But it doesn’t make up for everything that happened beforehand, since a lot of this script tows that familiar company line I’ve been reading in every screenplay for the last three years.

It’s 1946 at Vassar College. This is where innocent and sweet Helena Beam meets girl-boss energy Bow Brooks. Cut to 10 years later and Bow is running one of the biggest publishing houses in New York. She specializes in finding female writers.

After Helena has several miscarriages and is at an all-time low in her life, she runs into Bow and Bow offers her a job as her assistant. Helena’s husband isn’t fond of the idea but Helena takes the job anyway.

Helena is tasked with finding any female talent she can and so Helena puts all her effort into it. But the more she hangs out with Bow, the more confused she gets. Bow doesn’t seem interested in men and spends a lot of personal time with the female writers she’s signed.

After Helena does some digging, she uncovers the unthinkable (spoiler!). Bow is pulling a Milli-Vanilli! She’s taking female books and saying they’re written by men! When the press gets hold of this info, Bow’s empire comes crumbling down.

I’m telling you, someone needs to create a Reverse Bechedal Test. Cause, at this point, it’s getting silly. No man makes it out of this story unscathed. One of the first ones we meet tries to force himself on Bow. Helena’s husband is VERY DISCOURAGING about the fact that Helena can’t have children. We even have a female writer’s husband THREATEN TO KILL HER at one point. Lol.

It would be sad if it wasn’t so funny.

And the thing is, there was ZERO reason for Helena’s husband to be unsupportive. Bow is the bad guy in this movie. It was the perfect opportunity to create a supportive husband who could guide Helena through Bow’s evil emergence.

But nope. Gotta keep all men evil in 2022! There’s even an “all men are evil” She-Hulk monologue in here.

All that aside, the script has bigger issues.

This is a script built on its twist and what do we always say about that? When your script is built around a third act twist, it will likely die in its second act due to it running out of ‘story oxygen.’ If you’re saving up everything for that big finish, you won’t give the audience enough entertainment in the meantime.

Most of the second act we’re watching people hang out in rooms and talk about the publishing world. We’re getting these hints that something’s not right, which creates a little suspense. But a little suspense is not going to power a second act that lasts 55 pages. You need more than that. And there weren’t enough storylines to keep the reader invested.

I will say that I liked Bow being bad. I wasn’t expecting that for the reasons I brought up at the beginning of this review. You’re kinda not allowed to make women bad in movies right now. I mean, you can, of course. But most writers are afraid to. They believe they need to tow the company line. And the company line right now is that all female characters must be perfect. I literally just got done with a set of notes where I had to make the writer aware that all FIVE of his female characters were bada$$es. I don’t even consider this his fault! I think he just assumed what every writer assumes right now, which is that if there’s a female character in a script, she has to be a bada$$ or a Mary Sue. There can’t be a lick of negativity associated with her.

Here’s the funny part. This is a DREAM SCENARIO for you screenwriters. If everybody is only writing something one way, it gives you the opportunity to be the one person who writes it the other way. And, in doing so, surprise the heck out of the reader.

Which is what Kosann was able to do, at least with her ending. This should inspire you. All of you should be asking the question, “What am I not allowed to write in a script right now?” And then you should seriously consider writing EXACTLY THAT. Not in an “F YOU” way. You have to do it in a clever fashion that’s organic to the story you’re telling. But just think about how many people you can surprise by writing the things you’re not supposed to. Smart writers used to have this as one of the primary weapons in their writing arsenal. Today’s writers have forgotten about it altogether.

I liked the final act here. But not enough happened in the first two acts. There needed to be more plotlines and more fun plot developments happening.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned:There were no DISRUPTORS in this script. I kept waiting for a plot development that would DISRUPT the story – the kind of beat that makes you sit up and go, “Ooh, something’s happening.” In Black Panther, we’ve got this easy-going first act where everybody is casually gearing up for the next chapter in the kingdom. Things were starting to feel a little slow. And then – BOOM! – Killmonger shows up at that museum and steals the artifact. That’s a disruptor. All scripts need disruptors – sometimes big, sometimes small – to shake the reader up, to keep them uncomfortable. This script didn’t have that until it was too late.