Search Results for: F word

DIALOGUE WEEK IS HERE! – All this week, I’ve been breaking down dialogue scenes from the movies you love. Monday’s Dialogue Post is here. Tuesday’s post is here. And yesterday’s post is here.

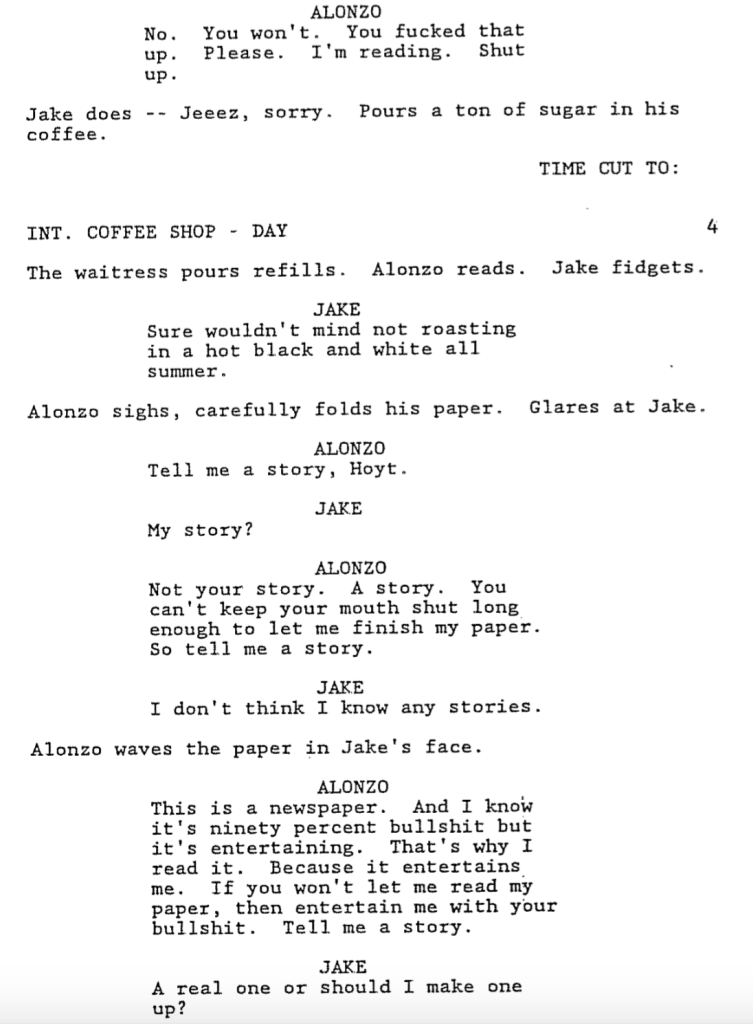

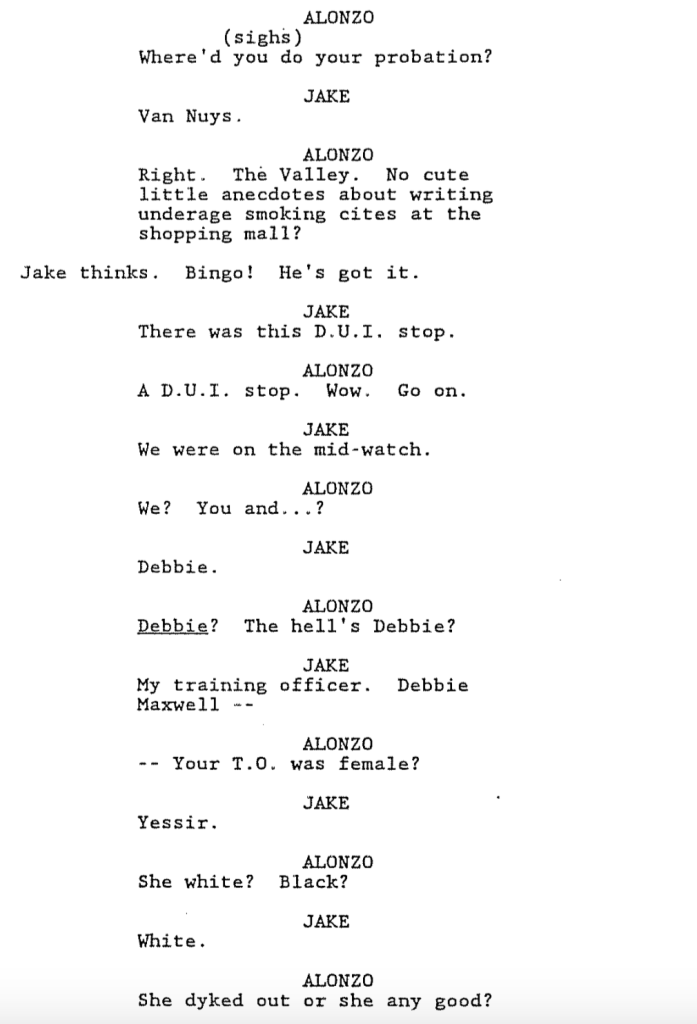

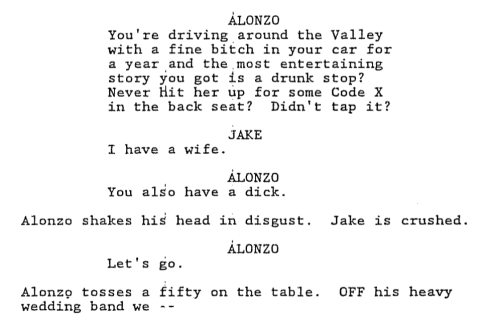

If you want to go to dialogue school, check out Training Day. It’s basically a 120 minute dialogue scene. Which brings us to our first lesson. Don’t focus on writing great individual dialogue scenes. Focus on creating great characters who can then write the dialogue for you. Alonzo is the ultimate dialogue-friendly character. And Jake is the ultimate straight man. Put those characters together and you have dozens of scenes where the dialogue writes itself. Let’s check out their famous first meeting together. For those who haven’t seen the movie, it’s about a young cop’s first training day with a veteran narcotics officer.

Okay, let’s jump into the easiest way to write a good dialogue scene. Are you ready? Give us one character who doesn’t want to talk and one character who does. That’s it! Boom! You do that, you will write good dialogue. I promise you. And that’s the whole premise of this scene. Jake wants to talk. Alonzo doesn’t.

I could stop there and you’d be halfway towards dialogue mastery. But I want to revisit this week’s theme. Which is that the best dialogue comes from what you’ve done BEOFRE the scene. Not during. We’ve built this entire movie around a dialogue-friendly character in Alonzo. He’s opinionated. He’s brash. He’s colorful. He’s un-p.c. He says the things you’re not supposed to say.

We then placed him across from a straight man. Dialogue-friendly characters work best with straight men. Two dialogue-friendly characters is like having two chefs in the kitchen. With that said, 2 DF characters can work. In Silver Linings Playbook, Pat and Tiffany were both dialogue-friendly and their scenes were great. But generally speaking, the rhythm of good dialogue follows a dominant and submissive pattern.

Which segues nicely into our next topic: power dynamic. Power dynamic is HUGE when it comes to dialogue. The very nature of somebody being “in charge” creates an imbalance. And that’s where the tension is. Tension is conflict. Conflict is drama. Drama is entertainment. In this scene, the power dynamic is obvious. It’s built into their job descriptions. But there’s a power dynamic to every conversation. Yesterday, the power dynamic was with the parents. They were in charge of the conversation. Chris was merely trying not to fuck up. In The Big Lebowski scene, Walter was on top of the power ladder, The Dude was in the middle, and Donny was on the bottom.

In this scene Alonzo’s power is SO MUCH HIGHER than Jake’s that Jake’s walking on eggshells the whole scene, which is what makes the conversation so fun. You can see Jake trying to say something – ANYTHING – to get Alonzo’s approval. If Jake and Alonzo are on the same power level, this scene doesn’t work.

It shouldn’t need to be said that dialogue reveals character. Which means you should be looking for opportunities to tell us about your character through the lines they deliver. Especially early in the screenplay, when we don’t know them yet. It just so happens there are a couple of prominent character revealing lines in this scene.

Alonzo is fed up that Jake won’t stop talking to him, so he demands that Jake tell him a story. Jake mumbles out that he does’t know any stories and Alonzo doubles down. Tell me a fucking story. “A real one or should I make one up?” Jake replies. I love this line because not only is it unexpected. But it reveals how indecisive and eager to please Jake is. I know everything I need to know about this character after this line.

Ditto Alonzo with his response to Jake’s story. Alonzo has no issues with telling Jake that his story sucked (he’s mean). And that getting laid is more important than preventing murder (seriously warped moral compass). In one sentence, we know just how screwed up and ruthless this man is. That’s good writing.

Let’s get into some minutiae. I love how Ayers says that Alonzo never stops looking at his paper during the conversation. It creates this literal barrier for Jake to bang up against for the first half of the scene. A lot of amateur writers assume you need to create the perfect circumstances for a conversation. It’s the opposite. You’re trying to find the angle that creates the most un-ideal circumstances for conversing. By forcing Jake to talk to a wall, it injects one more layer of conflict into a situation that’s already drowning in it.

Another example of this would be two people who meet at a loud club. They can’t hear each other. They have to keep saying, “What??” They misunderstand words, which leads to strange conversation tangents. That’s always going to be more fun than if they meet in a quiet room with no distractions.

I also love this exchange. “Have some chow before we hit the office. Go ahead. It’s my dollar.” “No, thank you, sir. I ate.” “Fine. Don’t.” Alonzo could’ve questioned what’s wrong with Jake here (“Who doesn’t eat at a diner?”). He could’ve challenged him (“You knew you were meeting me for breakfast and you already ate?”). Instead, he uses two words. “Fine. Don’t.” It’s savage. I actually shivered when I read those words. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the fewer words you use, the better. You don’t always have to craft a wonder-line.

Speaking of wonder-lines, there’s one flashy line in this scene. The newspaper line. And that’s appropriate. You shouldn’t be trying to win the lottery with every line. The very act of limiting yourself to one killer line ensures it will stand out. “This is a newspaper. And I know it’s ninety percent bullshit but it’s entertaining. That’s why I read it. Because it entertains me. If you won’t let me read my paper, then entertain me with your bullshit. Tell me a story.”

How do you write a line like this? Because I read a lot of amateur versions of this line. They come out more like, “Now you done fucked up. I can’t focus no more. All because you think you’re more entertaining than a newspaper. So if that’s what you think, then go ahead. Entertain me.” It’s clunky, not as clean. And doesn’t end with the same decisive POP that Ayers line does.

This is a case of a writer paying attention to his environment. You have this newspaper here. It’s already a major part of the scene. Let’s keep using it. But how can we use it to craft a great line? Start by asking questions. “What is a newspaper?” (It’s mostly bullshit) “Why is my character interested in this newspaper?” (it’s his calm before the storm) “What’s in here that he needs so badly?” (nothing really. But it’s one of the few things that entertains him. And since not many things entertain him, he values it).

You now have some PIECES you can use to form a line.

The answers to those questions pretty much form the basis of the first 75% of the line. Ayers then gives the line extra pop at the end by adding some wordplay. Entertainment and bullshit were featured words at the beginning of the line, so he brings them back at the end (“If you won’t let me read my paper, then entertain me with your bullshit”). There’s no science to this stuff but that’s one way of arriving at the line. Of course, for some writers, this stuff just comes naturally. Lucky bastards.

Finally, what I love so much about this scene is that while Denzel got a ton of credit for his performance, the truth is, it’s all there on the page. I don’t see that often. A lot of writers are wishy-washy and it opens the scene up for lots of interpretation. There’s no interpretation here. Any actor reads that beat of Alonzo keeping that newspaper up between him and Jake, and they know exactly who this character is and how to play him.

What I learned: Don’t over-describe pointless actions during heavy dialogue scenes. The less action you write, the more we can focus on what the characters are saying. Ayers writes barely any action here, and when he does, he keeps it to one line, except for a couple of times when it reaches one line and a quarter.

Now that you’ve read the scene, check out the finished product.

Schedule Change Alert! – Tomorrow, I’m reviewing Solo. Monday, Memorial Day, I’ll be off. Tuesday-Friday will be Dialogue Week. That pushes the Amateur Offerings Winner to June 8th.

As we get ready for Dialogue Week, I want to remind you of the basics. Because in order to write good dialogue, you have to first set up a situation that allows good dialogue to be written. The majority of the time, this will boil down to one law:

One character in the scene needs to want something. Another character in the scene needs to resist.

There’s a reason for this. You need “want” in a scene to give the scene direction. If someone doesn’t want anything, then why would we care what they say? In the same way a goal gives your character reason to act. A “want” gives your character reason to speak. The reason you want the other character to be resistant is because this creates CONFLICT in the conversation. And conflict is where dialogue is the most charged.

A simple version of this is a nerdy high school kid going up to ask a popular girl to prom. These scenes almost always work and the reason is that the dialogue “pedestals” holding the scene up are so sturdy. Character A wants something. Character B doesn’t want to give it to him. This is the secret nature of good dialogue. Even if you don’t dress this scene up with Diablo Cody like word magic, it’s still going to work because the situation is so strong.

On the flip side, if you write a scene where two friends get together to have coffee, and neither of them wants anything from the other, chances are the scene’s going to be boring. Audiences have a threshold for listening to conversations that don’t go anywhere, and it’s getting shorter every year. This is why, whenever you see a scene like this, it almost universally segues into, “I need your help with something.” Or the other character might say, “What do you want?” “What do you mean?” “You never ask me to coffee unless you want something. So what is it?” The scene then segues into the proper format for good dialogue. Want + resist = conflict = charged dialogue.

It’s also important to note that a “want” doesn’t have to be on the surface. In fact, most writers will tell you that it’s better if it isn’t. For example, let’s say a married couple who haven’t had sex in awhile are having a dinner night. The husband is hoping to get lucky. The wife isn’t. So the husband has put together this really romantic dinner in the hopes of convincing her.

Of course, he doesn’t say this out loud. He’s just hoping to spark the mood. So you have your want (to get lucky) and you have your resistance (she doesn’t want to). Therefore, when they talk about their day or how good the food tastes or that annoying co-worker, the dialogue’s still charged because we know what’s going on underneath that conversation.

Out of curiosity, I threw on Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle to see if it adhered to this rule. It’s a movie that has a lot of fun dialogue so it seemed like a great test bed. Indeed, it follows it closely. Here are the first seven scenes…

1) Spencer’s mom WANTS to make sure he has everything for the day. Spencer is upset that his mom busted in on him and is invading his space.

2) Fridge’s mom WANTS to make sure her son is studying so he doesn’t get cut from the football team. Fridge is elusive and assures her he’s fine.

3) Spencer uses the favor of doing Fridge’s homework to ask him if he WANTS to hang out this weekend. Fridge resists.

4) A scary old man from the nearby house WANTS to know what Spencer is doing there. Spencer resists, apologizes and walks away.

5) A teacher WANTS to know why Bethanny is on her phone during a quiz. Bethanny resists by saying she deserves to finish the call, ultimately leading to detention.

6) The gym teacher WANTS Martha to join the activities. Martha resists, giving her several reasons why gym is stupid.

7) The principal calls Spencer and Fridge into his office. He WANTS to know if they cheated. The two are elusive at first, but eventually Spencer cops to it.

I want to make something clear. Dialogue doesn’t fit into this perfect formula every time. Just most of the time. And that was on display in Jumanji as well. For example, after Spencer and Fridge leave the principal’s office, they start arguing with each other. There’s no apparent “want” here. It’s more of a reaction to something that already happened. But there was CONFLICT, which is why the dialogue still popped. It’s going to be fun discovering more of these variations next week.

But this is your starting point. Make sure a character wants something. Have there be some level of resistance from the other character, and you’re bound to write, at the very least, DECENT dialogue. As for writing great dialogue? Well, gosh-darn, you’ll just have to wait until next week for that. :)

Genre: TV Pilot – Drama

Premise: A group of Boston friends’ lives are changed after a member of their group unexpectedly commits suicide.

About: Today’s pilot comes from former comedy writer DJ Nash, who took a chance in writing his first drama. That chance paid off when ABC made it their first pickup of the season, positioning it as a This is Us counterstrike. Nash formally created Growing up Fisher and Truth Be Told. Ron Livingston and Romany Malco star in the show.

Writer: DJ Nash

Details: 57 pages

TV pilots are funny things. The shows with the longest staying power tend to have the weakest concepts. That’s because TV shows are character-driven as opposed to concept or plot-driven. Why is that? Well, if you’re writing 20 hours of television per season, that’s 18 hours more than a feature film. Seeing as it’s hard enough coming up with a series of cool plot points for a feature, you can imagine how hard it must be when you multiply that by ten.

Therefore, TV has no choice but to focus on character.

But this is what’s always confused me about TV. How do you get anybody’s attention with a lame character-driven concept? Like if you pitched me, “Four Boston friends have their lives uprooted when their friend dies,” I’d be like, “Annnnnnnd???” With a movie pitch, you know what you’ve got after the logline. With these things, it seems like a crapshoot.

Anyway, I’ll continue to stir fry that thought in my head while I dish out today’s review.

Rome, an almost-30 commercial director with the perfect life, is two minutes away from ending it. He’s got the pills. He’s prepping the deed. It’s only a matter of time. But before we watch him kill himself, we cut to his friend Jon, who has an even better life. The master of the deal and a real estate titan, Jon is currently on the phone, closing a deal in his kick ass high-rise office. How easy is it to love life when you’re killing it?

Cut to friend numero 3, Gary. Gary is getting the results from his doctor about whether his cancer’s back. His breast cancer. Yes, Gary is in the one percent of males who have breast cancer. But the good news is, he’s making it work for him. Gary bangs a new breast cancer survivor every week at his breast cancer support group.

Finally, there’s Eddie. Eddie hates his wife. Every day she drags him deeper into the pits of married hell. And while Rome’s about to off himself and Gary’s ready to get his results and Jon is ready to close the deal, Eddie is throwing all of his clothes into a suitcase. Eddie’s about to run away with another woman.

But then he gets the call from Gary that changes everything.

Jon just committed suicide.

That’s right. Not Rome. Jon. After he closed that deal, he leapt out the window.

The rest of the script has the guys coming together for Jon’s funeral and the gathering afterwards. The wives are all there, including Maggie, the latest girl Gary banged from his support group. Yes, their first date is officially a funeral.

As the group ponders the impossibility of someone like Jon, who had everything, ending his life, little hints pop up that there may be more to the story. When the guys go get tonight’s Bruins tickets from Jon’s office (going to Bruins games is a long-standing tradition), they get into Jon’s phone and find out that he made one call before he jumped. To Eddie.

The guys turn to Eddie, who looks back cluelessly. He never got a message. But later that night (major spoiler), when Eddie is alone, we see why he’s being so coy about that call. We finally find out who Eddie’s been planning to run away with. It’s none other than Jon’s wife.

I had mixed green feelings about this script.

I loved the early misdirect. Nash totally got me with Jon’s death. And I liked the ending twist, that Eddie was running away with Jon’s wife. Not only for the twist. But because you’re setting up a line of dramatic irony that can be drawn out for 5-6 episodes. Us and Eddie know that Jon may have killed himself because he found out that Eddie was sleeping with his wife. But the other friends don’t know that. And like any good line of dramatic irony, it’s the kind of thing that viewers will stick around for to see what happens when that bomb explodes.

My problem with A Million Little Things was the rest of the script, the middle part.

It’s mainly just a bunch of characters being sad, talking to each other, remembering things. And I think the problem here is that Nash didn’t use a good old fashioned goal. There are some writers who don’t think you should use goals in TV one-hours. That it’s more about “covering the bases” of each subplot. But I find that when there’s an overarching goal pushing the characters along, it gives the narrative an engine. We feel like there’s a PURPOSE to the story.

It’s not to say you HAVE to do this. If we’re inside of a particularly dramatic portion of a season, then each storyline (the A, B, or C) in an episode can be powerful enough that a uniform goal isn’t required. But my theory with pilots is that you can’t take any chances. You can’t even RISK a 3-5 minute down period. Because 3-5 minutes is all it takes these days for someone to decide your show is boring and never watch it again. TV viewers are not a forgiving bunch. I’ve met them.

With that said, there are still plenty of good things to talk about. When you’re writing a character driven pilot (as opposed to concept-driven pilot), you want to get an inciting incident into the story ASAP. Usually within the first 5 pages. This is to alleviate any suspicion that your show will be a group of characters talking for an hour. You need that “thing” to happen so that they know you mean business. A character dramatically killing themselves, via a misdirect, was a great way to get audiences hooked.

Building off of yesterday’s character development talk, we see again today how important it is to establish characters immediately. The first scene we meet each character in A Million Little Things is a scene where we learn the essence of who they are at this moment in their lives. Gary has breast cancer. Eddie is about to leave his marriage. Rome is suicidal. One of the biggest mistakes I see amateur writers make is they take 3, 4, 5 or MORE scenes to tell us what professional writers can tell us in one.

That’s not to say you can’t have characters of mystery, like John Locke in Lost. That’s a different discussion. But when dealing with straight-forward characters, you want to start developing them from their first frame.

A Million Little Things is obviously ABC’s attempt at a This Is Us killer. But it’s not as good as that show. One thing Dan Fogelman is great at it is he knows exactly how hard to press the melodrama pedal in each scene. He knows when it’s too far. He knows when it’s not enough. He knows when to alleviate tension with a joke. He knows the right tone that joke needs to be.

A Million Little Things is more hit and miss in these categories. There’s a scene late where they’re at the hockey game and Rome reveals out of nowhere that he tried to commit suicide. It’s an odd moment for the admission and the aftermath is too heavy-handed (“With nothing to say, Gary does the only thing he can do. He puts his arm around Rome and gives his friend a hug. Rome cries harder. So Gary just squeezes harder.”)

But hey, Fogelman’s the master at this stuff so let’s not hang any competitors out to dry here. The pilot isn’t great but it’s got just enough presence to make it worth your time.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Whether it’s a movie or a TV show, the simplest plotline you can use that uniformly works is to start with a dead body. In other words, I don’t think this pilot gets picked up if it’s this same group and we don’t get a suicide at the beginning of the show.

Genre: Horror

Premise: A young teacher who’s recently moved into a small blue collar town tries to help a lonely boy, only to find out that he’s harboring something terrible in his home.

About: Antlers director Scott Cooper is on the verge of becoming the next big mainstream auteur. He’s got a really interesting resume, with movies like Black Mass and Crazy Heart, and most recently, Hostiles. It’s only a matter of time before he’s hired onto one of these mega-projects. And congrats to screenwriter Nick Antosca. His last movie, The Forest (a horror film with Natalie Dormer), wasn’t received well. To jump from that to this is a major coup. It’s the kind of jump that sets you up for those big studio gigs. A lot has been made over the years of how screenwriting is the one profession in Hollywood where people fail upwards. They have a box office bomb or a critically “rotten” film, yet they keep moving up the ladder. I see it the opposite way. How great is it that you can bomb with one movie yet, if you follow that up with a really good script, they don’t hold that previous movie against you? Antosca’s co-writer on this film, Henry Chaisson, is just coming into the business. Up until this point, he’s only written shorts.

Writers: Henry Chaisson & Nick Antosca (based on the short story by Nick Antosca)

Details: 95 pages (3/3/17 draft)

One of the things I’ve been telling you guys is that you can’t think linearly. It doesn’t work like that in this business anymore. Sometimes you need to go backwards to go forward, sideways to go up, and inside to make it back out. It’s why I wrote that article about fiction podcasts last month. And today we have an example of the buzziest version of that philosophy at play – short stories.

This is the 7th or 8th short story being turned into a feature this year. This is a legitimate way in, guys. I’m guessing this trend is rising because short stories are less of a commitment than scripts. In a world where everyone’s looking to cut time out of their day (as long as it isn’t the 2 hours they waste on the internet every morning), spending 20 minutes on a short story is a welcome break from the usual feature script commitment.

And the bar isn’t that high. I STILL can’t believe that terrible Mars short story sold. And it was like 800 words (a screenplay is 20,000). You guys are all capable of writing 800 words. Anyway, let’s check out if today’s short story fares better than that one.

Julia Grey is a 23 year old teacher who’s just moved into a small conservative poor town in the south. Like a lot of young teachers, Julia is full of hope and eager to change the tide of this place. She believes she can make a difference!

But the truth is, the kids who grow up here aren’t interested in learning anything. Kinda like their parents. The principal tells her as much. Your only job, he says, is to make sure they don’t light themselves on fire when they’re at school.

But Julia takes an interest in a young boy in her class named Lucas who is a talented artist. The problem is that he’s a social outcast and any attempt to communicate with him ends with him running out of the room. Julia senses there’s something wrong at home and decides to make a visit.

Lucas’s house is a disaster. It’s all boarded up. It’s rotted. It doesn’t take long to discover that Lucas doesn’t even live in the house. He lives in a tent out back. But if he’s living outside the house then… who’s living in it?

Even Julia’s not naive enough to find out on her own. But when she hears a child crying inside, she rips open the boards and runs in. What she finds are the corpses of two people on the floor, long since dead, a man and a child. It looks like the mystery of Lucas’s weirdness is finally solved. But not the crying child. That’s something Julia will find out about soon enough. You see, Julia just inadvertently released a monster…

This was a really well-written script. A couple of things stuck out to me right away.

In the first scene, we see Julia teaching a class of 4th graders. I want you to think about this scene for a second. Imagine you’re writing it yourself. How do you make a teacher teaching 4th graders interesting? It’s harder than it seems, right? And yet, I was totally into it. I had to stop reading to figure out why. And then it hit me.

Chaisson and Antosca introduced a third party into the scene – the principal. As Julia is teaching, the principal slides into the room and starts observing. She notices him and becomes nervous. What we realize is that he’s judging her. Specifically, he doesn’t believe she has control over her students. And as the kids get more and more out of control, that belief is proven. So the reason we’re into the scene is because we’re rooting for Julia to get this class back under control.

All of this is happening while the writers are slyly setting up the characters, as well as the main myth that will become the story’s centerpiece later on – the Wendigo. That’s good writing, folks.

From there, we cut to Julia sitting across from the principal in his office. This scene teaches us the value of SETTING UP AN INTERACTION with your description. Remember, you have the option not to set up anything before an interaction. We can just cut to these two talking. Or we can prep the situation and use that to add tension to the scene before it even starts. That’s what Chaisson and Antosca do with this brilliant setup paragraph:

He’s staring at her, hard to read. All kinds of distances between them – age, gender, culture. He was born and raised in this town — and it is significant to him that she wasn’t.

I mean WOW. We already know from this paragraph – before a word has been spoken mind you! – that this moment is CHARGED. I can’t wait to read what happens next. That’s good writing!

Yesterday I brought up character development and I want to expand on that because Antlers is an example of a story we’ve seen before, and therefore could potentially be boring. But it’s not because it creates two really great characters.

And it does this by following a simple rule: Establish what you want to establish about the character early, and hit it hard. Don’t tiptoe around what you’re trying to say. This is the time when you want to be blunt.

Right away, with Julia, it’s established that she’s not from here, she doesn’t get the class’s attention despite desperately wanting to, the principal hates her, and she’s an outcast in this town. All of this is conveyed in her first couple of scenes. I can’t tell you how many scripts I’ve read where I don’t know one-tenth this much about a character AFTER READING THE ENTIRE SCRIPT!

Moving onto Lucas, we know he’s a loner. We know he’s a weirdo. We know he’s sad. We know he’s good at drawing. All of this in his first three scenes. To me, both of these characters are 80% developed and we haven’t even made it out of the first act! So if there’s a lesson here, it’s that you can tell us so much about your characters in their first few scenes. And if you do that well, we’re going to care what happens to them regardless of how the plot turns out.

Because the truth is, the plot to this is almost too simple. Once we find out that the Wendigo is out there looking for them, it’s your basic “try to survive” horror film. But it works because of that heavy dose of character development early on.

Really enjoyed this one. A great example of how to write a marketable spec script.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: In general, bringing in a third party to any stale situation usually spices it up. That opening classroom scene went from a 3 out of 10 to an 8 out of 10 due to that ONE DECISION to bring the principal in and have him watch. So if you have two characters in a scene and it’s boring, you now know what to do!

Sneaky me snuck off on vacation these past two weeks. I tried to rig my WordPress to automatically put up posts. The result was, um, not what I had hoped for, which meant I was constantly popping in to do maintenance, all on my phone. It’s not fun to try and fix a post when you’re in the middle of a castle! Or looking at the biggest Picasso painting ever painted. For those interested, I went to Dublin and Spain. The above picture I took in a park in Spain called the Retiro (in Madrid). Easily the most beautiful park I’ve ever been in.

Anyway, this post is meant to keep you accountable. You are now 5 months into the year. You should be closing in on one completed script. So, are you there? If not, write more! Or vent your frustrations. Or offer encouragement. Or whatever you want to say. As long as it’s about writing or vacations! :)