Search Results for: The Days Before

Reviewing “Seven” in my newsletter brought me back to a time when screenwriters could change their lives overnight. All they had to do was a write a good screenplay and – BOOM – they were millionaires.

Those sales then did double-duty for them, as their names would be splashed all over the trades. This would result in everyone in town wanting to meet with them. Which would establish contacts for these writers that they could use to write high-paying work for the next decade.

What happened to that world and how can we get it back?

A number of things happened. For starters, the internet screwed up the agency’s con. A big part of how scripts got sold in those days was that an agent would send a script out (hard copies, remember, not pdfs) to 7 studios and because all parties were isolated from one another, studios would freak out, afraid to lose a hot spec to a competitor, and therefore bid on that script out of fear, regardless of it it was any good.

Once the internet arrived, Roy Lee, a producer now at Warner Brothers, created an online chat room where assistants could share their thoughts on scripts. Therefore, when a script went out this time, it got photocopied quickly and, within hours, everyone was reading it. These assistants now had a central location to share their thoughts on the script, which would allow a quick consensus on if a script sucked or not.

And here’s the open secret about agency-endorsed screenplays (both then and now) – most of them are bad. Now, that badness was being exposed. So that previous strategy of scaring studios into bidding on bad material didn’t work anymore. This killed a lot of sales that would’ve gone through in the previous era.

Another thing that happened was that the studios all agreed not to share sale numbers anymore. They did this because the news stories about scripts selling for 2 million dollars were driving up script prices. So if you stopped telling people how much a script sold for, the trades were less likely to write a big story about them. And this would allow the studios to bring script prices down to a reasonable level.

I still don’t understand why agents agreed to this. It’s in an agent’s best interest to promote a big spec sale because it will get their client more work as well as themselves more money. The conversation may be more nuanced. I know that, sometimes, a script would sell for a lot less than expected and, in those cases, the agents would want the script price to be vague. That way they could hint that it was bigger than it was.

But just the fact that the trades no longer posted these numbers hurt the script sale business immensely.

But now we get to the biggest reason spec script sales plummeted – THE SCRIPTS WERE BAD. Go ahead and read some of these old million dollars sale scripts. Or just go back through my archives. They’re in there. These scripts were average at best. And so, when they got made, they didn’t make enough money. And when that happened enough times, the studios said, “We’re not following that carrot anymore. We know where that carrot leads.”

The inflection point was 2014’s Transcendence, with Johnny Depp. That was a spec script. That was an expensive movie. And it just SAT THERE. Nothing happened in that screenplay (which I erroneously gave a decent review to). So nobody showed up. And I specifically remember the drop-off of script purchases that occurred after that movie’s first weekend. And the market never recovered.

Which leads us to the post’s big question: How do we bring spec script sales back?

For one, trades have to write about them again. One of the reasons spec scripts became so big in the first place was all the stories that the trades would write about them. If someone sold a big spec, there’d be a giant Variety article that would go into detail about the writer – where he came from, how he conceived of the idea. It was exciting! I still remember reading that article about those valet guys who wrote a spec about valets that made a million bucks. Those stories drive interest in screenwriting. We need them. And nobody writes them anymore.

I’ve thought about writing them myself. But there is some conflict-of-interest. When I have made some calls to get info and developed relationships with those buyers in the past, it would get complicated when I would then have to review the script (or another script from the same production company). I’d notice that I was a little easier on the material than I would normally be. But it’s something I should consider because that sacrifice could be worth the industry having a place where they can consistently read the latest screenwriting success story. Let me know in the comments if you think I should do this. It might mean not being able to review those scripts, though.

We need to publish script sale numbers again. Agents and managers should be promoting those numbers like crazy. It’ll lead to their clients making more money on future projects! Which means more money for them! I don’t care if these spec sale prices are low at first (250 grand, 350 grand). They will grow over time if we keep our foot on the gas and keep writing about these sales.

But the biggest thing you, the writers, need to do is write THE RIGHT SCREENPLAYS and then do a GREAT JOB WRITING THEM. These scripts don’t only have to be as good as the mega-franchise movies. They have to be better. Cause they don’t have any IP behind them. So if you’re a studio taking a chance on one of these scripts, the script has to be really impressive.

Ever since the spec sale business died, the primary measuring stick for a screenplay has been The Black List. And The Black List has become the opposite of the spec sale business. It’s become the Nicholl Fellowship List. It promotes intellectual screenplays over commercial screenplays. It still serves the purpose of getting writers recognized. But it doesn’t help the spec sale trade at all.

To revive the spec sale trade, you have to start with the kind of movie template that actually makes money. Former spec script mainstays like Comedy (The Hangover), Dark Thrillers (Silence of the Lambs), Romantic Thrillers (Fatal Attraction), and Romantic Comedies (Notting Hill), have been relegated to streaming services. Which means you can still make money off of them. But it’s not going to be for a big paycheck.

The movies that spec writers can still write these days and realistically sell for big money include the Action movie (Beekeeper), Action Comedy (Spy), Horror (Us), Buddy Cop movies (Central Intelligence), Guy/Girl with a Gun movies (John Wick), Fun Slasher movies (Scream), Heist (Ocean’s 11), Biopics (Elvis), Based on a true story World War 2 movies (Saving Private Ryan), Contained Thrillers (The Mist), Fun Undercover Cop movies (the original Fast and Furious, Point Blank), Ensemble Big Concept (Knives Out) and to some extent, the general high concept script, as long as it’s upbeat and therefore would sell a lot of tickets (think Jurassic Park or Free Guy).

This is not to rule out updating old templates, like the Submarine movie (Crimson Tide), the Action-Crime movie (Heat), Hitchcockian Suspense movies (Gone Girl), The John Carpenter movie (Escape from New York), The John Hughes movie (elevated teen fare), the big-budget Western (The Magnificent Seven), the pirate movie (Pirates of the Caribbean). Or just that bonkers wowza idea that’s never been done before.

To be honest, you could still write a rom-com that sells for a million bucks *if* you find a clever way to reinvent the genre. Actually, that’s the best way to sell any script for a million dollars. Reinvent the genre. Reinvent any of the movie-types I listed above and you can be a millionaire. I’m not kidding.

Once you’ve got your concept, the hard work begins. This is where the article comes full circle because “Seven,” in many ways, is the perfect spec script. It’s not only a clever idea. But it’s one of the few spec scripts I’ve read where it’s clear that the writer gave 100% on every page. There’s zero laziness in “Seven.”

The core reason that the spec boom died out was that the movies that resulted from those scripts didn’t consistently deliver. And that’s cause the scripts were weak. Most of the value in those scripts was concentrated in the first act. Which meant audiences would go to the theater, enjoy the heck out of the first 30 minutes of the movie, then became increasingly bored with every passing ten minutes. They’d leave the theater with zero energy and wouldn’t recommend the movie to anyone.

So if you want to revive big spec sales, it’s up to you guys. It’s up to you as to how much you want to work on your screenplays. This is why I tell writers, field-test your concept so you know it’s good. Cause if you do that, you know you can spend a year making your script perfect (e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com – $25 for a logline eval). Cause you already know people are going to want to read it whenever you finish.

Then, get feedback after each draft (figure at least six drafts)! Figure out which characters aren’t working. Make them better. Figure out where readers are losing interest then upgrade the plot in those areas. Even out your tone with each successive rewrite. Stay open to new exciting directions you can take your screenplay, even if it means extending your original deadline. Your goal should be to write something where you can honestly say, “I can’t make this any better.”

The thing you will never be able to control is writing an objectively great screenplay. You just never know how people are going to react to a story. But what you can control is writing the best possible screenplay YOU’RE CAPABLE OF WRITING IN THIS MOMENT IN TIME. I felt that way with “Seven.” I don’t feel that with many other scripts I read.

Let’s change that.

Then let’s sell some damn million dollar scripts.

One of the weirdest coolest crossovers I’ve ever read. Everything Everywhere All at Once meets Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind meets When Harry Met Sally!

Genre: Rom-Com/Quirky/Sci-Fi/Drama

Premise: A relationship is put to the ultimate test when time ripples keep reinventing one of the partners, forcing the relationship to begin again… and again… and again… and again… and again…

About: I know Max Taxe has been writing since, at last, 2010, as I received a few e-mails from him back then. All that hard work is finally starting to pay dividends as he got a movie on HBO Max last year called, “Moonshot.” And now, this script is headed to Netflix via mega-production company, 21 Laps. I’m about to share some news that some of you may not like. But yes, this is yet another project that started out as a SHORT STORY. That’s how it was purchased (a pitch with a short story). Taxe then adapted it after he sold the rights into a full screenplay.

Writer: Max Taxe

Details: 98 pages

Donald Glover for Miles?

Donald Glover for Miles?

Writers are back!

It looks like the studios and streamers finally wised up, realizing that every story AI produces reads like a fairy tale written by the Terminator. I’m not all mad at the strike though. It did give us The Golden Bachelor and 90 minute episodes of Survivor. And, of course, where we would be if Dave Filoni couldn’t write more episodes of Ahsoka? I’m not sure my Wednesdays could survive such a calamity. I need to find out what those space whales are up to!

I’ll be honest, I wonder how many professional writers wrote during the strike. Cause I know all any TV writer says is, “There’s not enough time.” So imagine if you had six months to catch up on your scriptwriting. Would Craig Maizon take that opportunity to scribble out a few Season 2 episodes of The Last of Us?

I guess we’ll never know.

But here’s something I do know. Today’s script subject matter is my kind of jam. You’ve got a little love. A little comedy. An offbeat writing voice. And then you’ve got a splash of sci-fi to disrupt it all.

Still one of my favorite scripts (that was sadly ruined by Pete Davidson, just like he ruined my chances with Emily Ratajkowski) was Meet Cute. It was similar to this premise. Girl uses a time machine to construct the perfect date. Why couldn’t the writer’s strike have disrupted that casting?

But will Ripple’s quirkiness overwhelm its charming premise? I’m going to channel my own personal 1.21 gigawatts to find out.

Miles and Sadie are two 30-somethings who have been unlucky in love. So much so that when they first meet, they openly admit that they expect their date to be a failure. But by doing so, they strip all expectations from the date, which allows them to have the best date of their lives and fall in love.

A few weeks later, some internet poster named XxNavi47xX says he’s from the future and provides winning lottery numbers to prove it. These numbers turn out to be correct and a bunch of people win money. However, this causes the first of many time ripples. Miles and Sadie’s cat, Trouble, turns into a dog. The way a ripple works is that you remember your past existence for about an hour, but that memory permanently disappears afterwards.

After this happens a few more times, Miles starts getting scared that a ripple may disappear Sadie (it already disappeared the all-girl band, Haim!). The internet connects him with a guy named Oz who has developed a system to help memories survive ripples. You write down your memories and a server bounces them back and forth a million times a second continuously so that they can migrate from one ripple to the next.

This way, when Sadie does, of course, disappear, Miles remembers her and goes after her. But, unfortunately for our lovebirds, the craziness is just getting started. It’s followed a month later by another one. And then a few weeks later by another one. In one reality, she’s the lawyer she was originally going to be before her lawyer father committed suicide. In another, she’s a hairdresser. In yet another, she’s a movie star.

Miles is able to keep finding her and get back together with her but then Navi is forced to go on the run which really starts affecting the timeline. Miles is forced to through thousands of ripple variations to find Sadie again. We can see the toll it’s taking on him and realize it’s not sustainable. At a certain point, Miles is going to have to decide whether his love for Sadie is strong enough to live this hell of an existence.

You know, I always say, if a script takes more than two genres to label, that means you’ve got a script that doesn’t work. Well, this might be the first exception. It really is a myriad of different genres and yet, somehow, it works.

I’m surprised they bought this concept as a short story pitch. Because with a script like this, it’s all about the execution. And the execution for something that exists in the murky world of time travel can go bad quickly. It’s a testament to the power of short stories in this new ultra-attention-deficit-disorder industry. I don’t think this sells if it’s only a pitch. The short story was enough of a bridge to allow 21 Laps to see where the script might go.

And it goes to some interesting places.

It starts off as this straight up rom-com, almost to the point of being cloying. The “meet cute” at The Apple Pan restaurant is too cutesy-pootsy for its own good, even as it attempts to subvert expectations.

I wouldn’t even say the script was saved by its first ripple. Because when that first ripple happens, we don’t know how deep into the concept the writer is going to go yet. It turns out, very deep.

Once we’re in the throes of over a hundred ripples, we start to feel the desperation of Miles, as well as the realization that he may have to come to terms with letting Sadie go. Cause the ripples just keep happening and his entire existence is dedicated to re-finding Sadie and starting their love story over again.

But just imagine how taxing it must be to do that hundreds of times over, with a new person that has a completely different past, only to lose them again a week later. It’s pure misery. And one of the most powerful moments in the script is when the 700th version of Sadie says to him, I’m not the person you met. I’m a copy of a fragment of a reincarnation of that person. You just need to move on.

It was heartbreaking.

But I think where Taxe really earns his writer’s stripes is in how he controls the technical side of the story. He uses this time traveler guy – Navi – as a way to influence the frequency and severity of the ripples. At first, when he’s in hiding, just posting anonymous internet comments, the ripples are soft and spaced out. But when he goes on the run, the ripples start getting more intense. Then, as the government closes in on him, they grow more intense still.

This ensures that the script is constantly changing. I always complain about how screenplays get predictable, both with what happens and how the story is paced. The way Taxe treats Navi guarantees a lot of variety in both these departments.

And I loved how, when the government finally caught him, it meant that whatever timeline we were in was the final one. No more Ripples. And in this timeline, Miles and Sadie had decided never to be together. So we’re really sad that their love story is over.

I will say this as a sci-fi geek (spoiler adjacent). There was a part of me that REALLY WANTED Sadie to be Navi. And we find out that the reason she’s been resetting her timelines was to get to a timeline where her dad was still alive. But, of course, that would’ve created some other plot messiness that might not have been able to be explained. So I’m okay with Navi being random.

I went back and forth on whether this was a double worth the read or an impressive. Cause the first half is above average. It’s enough to keep you turning the pages. But it wasn’t until I got to the last 40 pages that I truly got pulled into the story. You know what, though? It got me at the end. That final ending beat was perfect. And when a script leaves me on that high of a note, I gotta give it an impressive, man!

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of the best ways to get noticed is to deconstruct a genre. Take a well-known genre in a direction we don’t expect. This script takes romantic comedy to the last place I expected it to go. If you want to learn how to deconstruct a genre, read “Ripple.”

Today (Thursday) is the deadline for First Page Showdown. You submit the first page of your screenplay. I pick the five best first pages and post them tomorrow. The site votes on their favorite. Whoever wins gets a script review next Friday.

What: First Page Showdown

Send in: Title, Genre, Logline, and a PDF of the first page of your script

Deadline: Thursday, September 21st, 10:00pm Pacific Time

Where: e-mail all entries to carsonreeves3@gmail.com

Out of curiosity, I went back and looked at the opening page of the last five scripts I gave good reviews to ([xx] worth the read or higher). Here they are:

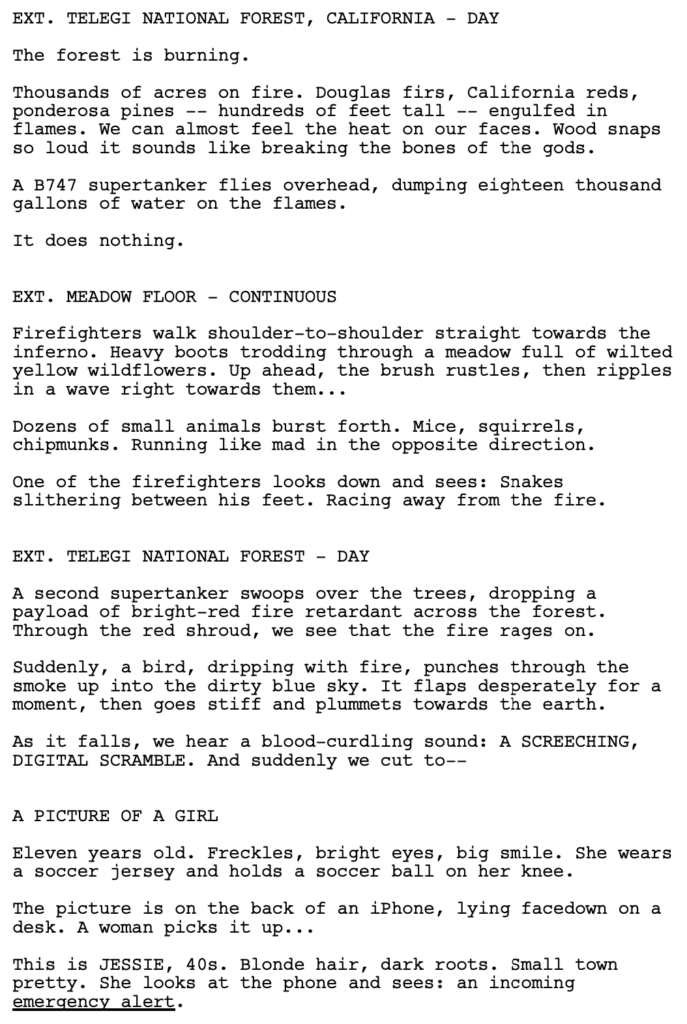

Black Kite – After a devastating wildfire wipes out a small California town, a teenage girl is missing and presumed dead. A year later, an obsessive mother and cynical arson investigator begin to suspect that she’s still alive…and in the clutches of a predator.

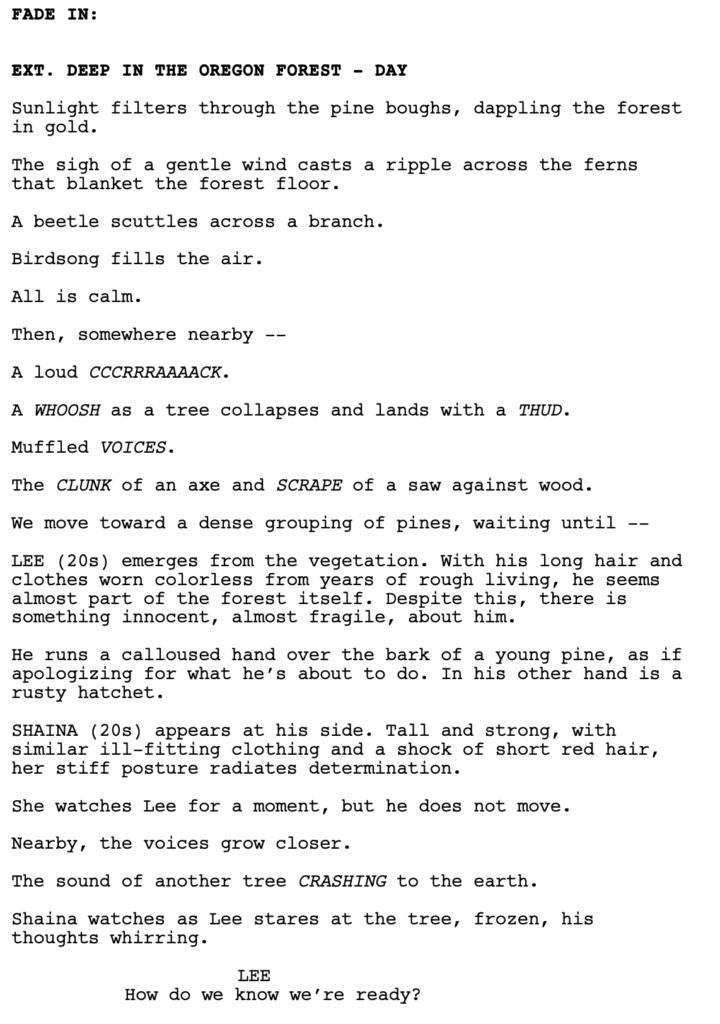

Wayward Son – When her estranged son returns and takes her grandson in the night, a veteran park ranger sets out to rescue him from the clutches of a mysterious cult deep in the Oregon woods.

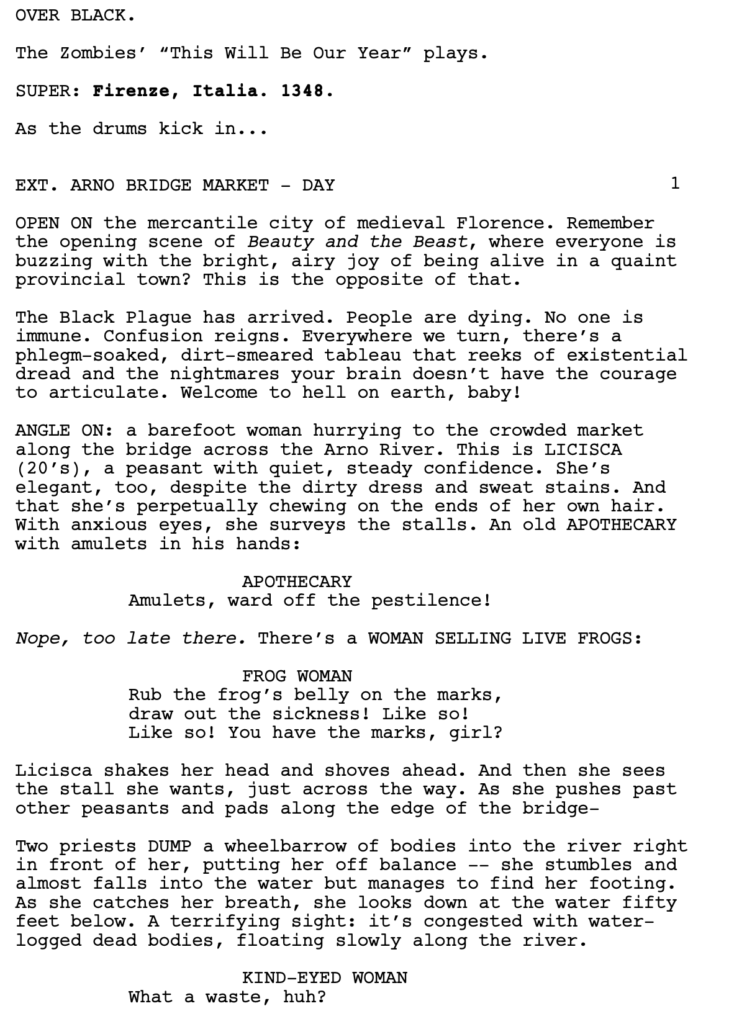

The Decameron – During the Black Plague, a group of rich Italians head off into the countryside to party out the plague in a beautiful villa.

Wild – A werewolf living on a remote farm with her older sister takes in a thief on the run just 72 hours before the next full moon.

The Pack – A documentary crew in contention at the Emmys for their film about wild Alaskan wolves is hiding several big secrets about their troubled 3 month shoot.

You’ll notice that not all of them start with a great first page. I’d say that both Decameron and Black Kite start strong. Wayward Son starts out all right. A little bit of mystery there. Wild throws in the “scar necklace” which makes me want to keep reading so that one was pretty good. And The Pack starts off fairly weak. This would seem to dispel the myth that a strong script is synonymous with a strong first page. Which would seem to indicate that our little showdown this month is irrelevant.

Ahhhh, but it so very much is relevant, my friends.

You see, a script read can be broken down into two categories. Those categories are, “Hafta Read” and “Give It A Shot.” “Hafta Read” is when the reader has to read the whole script whether he wants to or not. Every script I read for the site is a Hafta Read because I need to be able to discuss the story in the review!

However, nobody in the industry has a screenplay review site. For that reason, many of them read scripts from a “Give It a Shot” perspective. They’ll read the whole script if it’s good. But if something rubs them the wrong way early or they just don’t like what they’ve read, they’ll give up on it. And they’ll do it quickly.

Some of you might be confused about when this happens because, say, if a production company wants coverage on a script and gets their secretary to write that coverage then that secretary is in a “Hafta Read” scenario. There are many instances throughout the industry where someone has to read the whole script.

But a lot of scripts make it into peoples’ hands through favors. And unless the reader is close with the writer, those favors almost always exist as “Give it a Shot” reads. This just happened to me recently. I went to visit extended family and one of my family members who knew what I did had a friend who had written a screenplay and asked me if I could check it out for them.

So I did. But I did so under a “Give it a Shot” pretense. If it was good, I’d keep reading. If it wasn’t, I was out. Particularly because I had a ton of work to do at the time. It was clear to me right away that the writing wasn’t up to professional standards. So I didn’t make it past page 5. And I was being generous. I probably went 3 pages longer than I needed to.

Favors are so prevalent when it comes to reading something that most of the scenarios you’re going to be in are of the “Give it a Shot” variety. You’ll cold e-mail a manager who likes your logline and says he’ll check out your script – send it along. I guarantee you, you are not in “Hafta Read” territory with that manager. They’re giving you five pages tops.

That’s the thing with “Give it a Shot.” It means something different to every reader. For some it might mean giving the script 10 pages, others 5, and still others, 1. And the less close the reader is to the writer, the lower that number gets. If I get a script from a friend of a cousin of a friend, I have .0001 level of commitment to that person. So when I open that script, I’m ready to bail if you don’t hook me by THE FIRST PARAGRAPH.

I bring all this up to remind everyone reading this post that it’s highly likely that any industry person you can get your script to is a “Give it a Shot” situation. And because of that, writing a great first page matters. Cause the reality is that these people will be putting outsized importance on your first page and using it to determine whether they like you as a writer and if they want to keep reading.

Even if you have a few people in your rolodex who will give you “Hafta” reads, what happens if they like your script and decide to pass it up to the more important people, the ones with the power to greenlight, the ones with the money? All of a sudden you’re right back in “Give it a Shot” territory, and what are you going to do? Tell your contact to hold off while you write a new first scene? Why not write a good first page already so you can win over both of them?

Okay, Carson. But some of those scripts you gave good reviews to were able to overcome average first pages. So how did they find success? Look, there is a “luck” component to all this. Sometimes you give your script to the right person at the right time and they’re looking for something exactly like that so they’re giving your script a lot more leeway than on a normal read. And if you get somebody with power who likes your script, your script all of a sudden has buzz and becomes a “Hafta Read.”

Even if I wasn’t reviewing scripts for the site, I would still consider the top 5 Black List scripts “Hafta Reads” because they’ve been vetted and that gives me enough confidence to read through any trouble spots the scripts might have.

But most of you aren’t there yet. I wouldn’t even consider low-tier professionals in Hafta Read territory.

You know, the bar for opening pages used to be a lot lower. Even back in the 90s, when the competition was fierce, most readers just wanted to see that the first page was well-written. That the writer could construct proper sentences, the prose was easy to read, and the eyes moved down the page quickly.

But these days, with our mega-ADD addled brains, that’s no longer enough. You need to have that AND you need to have something compelling going on, something that pulls the reader in right away. It’s a lot to ask of one page but if you were hoping for a quiet relaxed career in the writing world, go be a librarian. This is professional screenwriting. It’s where the big boys play. The bar is high.

It’s going to be interesting to see what pages make the cut for tomorrow’s Showdown. Maybe I surprise myself and include a page where nothing is happening but the writing is outright stellar. I just don’t know. But I’ll tell you this. I’m excited to find out. And I’m even more excited to see how good the winning script is.

The First Page Showdown deadline is this Thursday at 10pm! Here’s how to enter!

Genre: Comedy

Premise: A 13 year-old boy blackmails his favorite pop star into being his best friend.

About: This script received 8 votes on last year’s Black List. Writer James Morosini got some nice buzz a few years back for his indie film, I Love My Dad, about a dad who catfishes his son on a dating app in the hopes of getting to know him better.

Writer: James Morosini

Details: 94 pages

Brie Larson was already a pop star in a former life. So she should have no problem playing one.

Brie Larson was already a pop star in a former life. So she should have no problem playing one.

I know people are saying the Black List is dead.

I think one of you quoted a Hollywood agent who said, “If it’s on the Black List, I know it’s bad.”

Believe me, I’m not supporting the last four years of this list. I know the quality has gone down.

But let me ask you a question. If the Black List is irrelevant, how does Hollywood find writers anymore? There aren’t spec sales anymore. So if there are no specs and no Black List, how do writers get discovered?

There are only two avenues left. Writer-directors (direct your own scripts, bypassing the pipeline). And television writing. Get on a writing staff, make a name for yourself, then write a feature script that your agent sends out and hope someone likes it.

I’m not sure I buy the Black List is dead hype entirely. There are still ten legitimately good scripts to come out of the list a year. It just sucks that you have to wade through 70 other writtenly-challenged ones to find them.

Let’s find out if today’s script is one of the 10… or one of the 70.

Benny is a chubby 13 year old gay super-fan of Alice Foxx, who I’m guessing is inspired by Ariana Grande. That’s because Alice is a straight up b*tch. She spends the majority of her time complaining to her sister/manager, Nicole, about the mistakes that are made during her concerts (“The sync was off!”).

But Alice is not the nastiest character in the story. That title goes to Rick Ferraro, an aggressive paparazzo who feels like his early pictures of Alice made her a star and is bitter that she no longer gives him the time of day.

After her latest LA concert, Alice heads to the In and Out on Sunset (a woman after my heart) and dials up a double-double in the drive-thru. It just so happens Benny, who also needed to get his In and Out on, spots her, and chases her a few streets down where she parks on a side street to eat her In and Out in privacy (there’s nowhere around that In and Out to park but I’ll allow it).

While slinging delicious farm-fresh fried potatoes at her tonsils, the evil Rick Ferraro pops up and starts taking pictures of her. Alice tries to get away but accidentally hits him. She stops, apologizes, but he gleefully screams that he’s going to sue her. Enraged, she slams on the gas a second time, and with this one, she knocks him down hard enough to kill him! Just as this happens, Benny pulls up. Alice and Benny share a look and then Alice speeds off.

Benny reminds Alice about their mutual secret at Alice’s next fan meet-and-greet so Alice takes Benny backstage and asks him what he wants. Benny simply says, “I want to be your friend.” Alice figures she can give Benny the best day of his life then send him on his way and the problem will be solved. But after the day to end all days, Benny only wants to spend more time with Alice. In fact, he wants to spend the rest of his life with her.

Back in the 80s, Bill Murray came to Ron Howard with a project he wanted Howard to direct. Howard read the script, met with Murray, and told him he couldn’t see himself directing the project. “Why not?” Murray asked. “Well, there’s no one to root for in this story.” Howard said. This single answer enraged Murray so much that he blacklisted Ron Howard and never talked to him again.

Murray, a great performer, may not have been educated on the world of screenwriting at the time. But it’s a legitimate concern. You need the audience to root for at least one of your main characters.

You’d think we’d root for Benny here. He’s awkward. He has no friends. He’s sweet.

But Benny isn’t a real person. He’s so naive as to be oblivious to reality. He doesn’t live in a real life universe. His parents are dead and his grandma is, conveniently, asleep all the time, allowing this 13 year old kid to disappear for days at a time. His only language is weird dancing and regurgitating pop song lyrics. Benny is a caricature. He’s not a character.

That leaves us with Alice. Alice is a more complex character but she’s one of the most unlikable people ever. She’s selfish (she skips a Make-A-Wish meeting because the experience would be annoying). She doesn’t appreciate what she has. She’s always complaining. She’s annoyed by Benny and is always looking for ways to ditch him. So, of course we’re not rooting for her.

So who’s left? Nobody. And I’m sorry Bill Murray but, if there’s no one to root for, it’s hard to become engaged in a script.

But maybe they cast someone as Benny who’s so charming that we do root for him. It’s happened before. Well, even if you can get on board with Benny, this script still has major tonal issues. I talk about tone a lot on the site and I rarely go into detail about what ‘tonal issues’ means. So let’s give it a shot.

It boils down to a script that vacillates recklessly between two opposing extremes. For example, Benny is threatening to put Alice in prison for the rest of her life if she isn’t his friend. Seconds later, he’s bumbling around like a drunk weirdo doing a meme-worthy dance. I’m not convinced you can have it both ways. Is this a serious movie about a stalker or is it a straight-up comedy? The script keeps bouncing back and forth between the answer to that question.

With this type of story – and I’ve read dozens of scripts that have had this setup – they work best when the main character is competent and calculated. You need a character who we believe is able to execute a blackmailing plan in order to buy in. I suppose you could argue there’s something scarier about an idiot blackmailing you. Because they don’t use logic. But Benny is so pure that I never once believed he would give Alice up.

On top of all that, the screenplay feels rushed. The writer never commits to any details to make me believe this is a real pop star. If you’re covering a specific subject matter in your script, you have to give us AT LEAST ONE THING about that subject matter that we don’t know. In one of my favorite movies of the year, Blackberry, we get this early scene in the boardroom that goes into highly specific territory about how the Blackberry works. That helps sell us on the world, which, in turn, pulls us in.

If anything, I got the opposite impression from “Pop.” Alice sells CDs at her concert! Because we all know those Gen Z 15 and 16 year olds love CDs. It’s just as important to them as improving their laserdisc collection.

If there’s a caveat to this analysis, it would be that Morosini is a writer-director. Writer-directors are more adept at attacking potential tonal issues than when you separate the writer and director. I saw this in Birdman’s script-to-screen. I saw it in Three Billboard Outside Ebbing, Missouri’s script-to-screen. However, you got a lot of convincing you need to do to get me to believe “Pop” is in the same category as those films. Benny’s goofiness undermines everything the script is trying to do, which is pose a threat to Alice.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The official definition of a caricature is a distorted representation of a person in a way that exaggerates some characteristics and oversimplifies others. Which explains the character of Benny to a “T” (exaggerates: speaks mainly through his wild dances. Oversimplifies: Literally the only thing he cares about in life is being friends with a pop star). Caricatures can work with secondary characters in comedy scripts. But I’m not sure I’ve ever seen one work in the lead role.

Do we have a new Top 25 script on our hands!!?

Genre: Thriller

Premise: After a devastating wildfire wipes out a small California town, a teenage girl is missing and presumed dead. A year later, an obsessive mother and cynical arson investigator begin to suspect that she’s still alive…and in the clutches of a predator.

About: Dan Bulla is one of the newer writers on Saturday Night Live, joining the longstanding sketch show in 2019. He also wrote an episode of the Pete Davidson show, Bupkis. This script finished on last year’s Black List.

Writer: Dan Bulla

Details: 111 pages

Mark Ruffalo for Nick?

Mark Ruffalo for Nick?

It is the most wonderful time of the year.

No, I’m not talking about the return of football. I’m talking about the U.S. Freaking Open! I’m currently bouncing around between watching 128 first round matches, having the time of my life.

It was during this trip to nirvana that I thought to myself, “You know what would be nice? Reading a script about a forest fire!” Hey, I can’t defend how my mind works. It does what it wants to do and I try and keep up.

Little did I know I’d be stumbling into a bona fide banger of a screenplay!

40-something Jessie lives in Avalon, California – one of those small Northern California towns in the middle of endless forests. And on this morning, it’s a bad day in Avalon. A massive forest fire creeps up out of nowhere, causing a mad dash to get out of town.

Jessie and her husband, Ken, are assured by the local police that the high school has been evacuated, meaning that their daughter, Wendy, is okay. Still, they barely escape and get to the rendezvous point, where they learn the devastating news that Wendy secretly ditched school that day.

Cut to Wendy and a couple of her friends goofing off in the forest when the fire approaches. They make a run for it but get split up, and Wendy finds herself on a road that is blocked in both directions. Just before she’s about to die, a red pickup truck arrives and a man named Randy saves her.

Cut to a year later and we meet Nick, a private fire investigator. Nick is in Avalon to meet Jessie, who says she has evidence that the fire was not, indeed, caused by a downed electrical generator, but rather by arson. Nick has a lot invested in Jessie’s claim because he’ll receive a giant windfall of cash if he can get the electric company off the hook.

Unfortunately, Jessie seems flat-out crazy these days. She lives in an RV in this shell of a town, collecting burned-up debris in the hopes of proving there’s more to this fire than meets the eye. Nick knows that her theory is weak from the get-go and considers turning around and leaving immediately. But Jessie’s emotional plea to help her figure out how her daughter died gets Nick to stay.

The next day, Jessie shows Nick a mysterious gray line she found in the burnt-up forest. Now Nick is interested. This line implies that the fire was started by arson. Which means somebody planned this. He further figures out that Wendy may not have died after all. Could these two things – the arson and Wendy’s disappearance – be related? And, if so, who, in town, has her? Nick and Jessie will have to team up to find out!

Let me say that this is the first script I’ve read in months where I thought I was a lot earlier in the script than I was. I thought I was on page 60 and it turned out I was on page 85! Usually, it’s the opposite. I think I’m on page 60 and I’m on page 20.

That’s screenwriting code for: this script was awesome.

I liked the script even before I opened it. It’s a fresh concept. We don’t usually see serial killers and wildfires in the same story space. It’s a unique combination. More importantly, it rewrites the investigation narrative. Usually, when we read about a killer or an abductor, it takes place in a city, which means that every investigatory beat in the story is one we’ve already seen before.

Here, the investigatory beats are all unique because we’re in a bunt out town in the middle of nowhere. We’re not going to apartments in Brooklyn asking cousins when the last time they saw Jenny was. We’re in a forest examining dead animal carcasses. I can’t emphasize enough how important this is. Readers read the same stuff OVER AND OVER again. So if your plot provides a world with a bunch of fresh scenarios for your characters to engage in, you’re up on every other screenwriter in the business.

As always, these scripts depend on authenticity. I always say to writers – if you’re writing about a specialized subject matter, you better know a lot more about that subject matter than I do. If I think we know that subject matter evenly, I’m done with your script. Cause I know you didn’t do any research, which means you’re not trying. I don’t have time for writers who don’t try.

I LOOOVED the opening forest fire scene here. It was SOOOOO intense. And the level of specificity to it was impressive (the way this fire spreads sounds eerily similar to what happened in Hawaii recently – and this script was written a year before that happened). There’s this moment where they’re desperately trying to get out of this logjam of cars and they finally break through and they’re racing against the smoke and they look over and there are these deers who are right next to them, also trying to escape. It felt so specific, like the writer was fully tuned into the sequence.

The writer also knows how to navigate the nuts and bolts aspects of storytelling. For example, there’s this early scene with Nick where the writer wants to establish that Nick knows what he’s talking about. You do this in screenwriting because it gets the reader on the character’s side. Readers LOVE when the character knows something that the average person doesn’t.

There’s this moment where Jessie is trying to convince Nick that a bottle rocket was the cause of the fire. Nick takes a look at the bottle rocket and the affected area and says this: “There’s deep char on the right side of the trees. Minimal char on the left. Burns rising, right to left, steeper than the slope. Branches all bent in the same direction. Foliage freeze. That means the wind was blowing right to left at the time of the fire. No odor. No sign of accelerant. It’s burned on top, untouched on the bottom. That tells me that a fully formed, advancing fire swept over this area, right to left, at about six miles an hour. The bottle rocket didn’t start the fire. It’s just some litter you found in the woods.” If there was any doubt that this guy is a fire expert, this assessment puts it to rest.

And then there’s this little moment early on that told me I was dealing with a guy who KNOWS SCREENWRITING. Jessie gets Nick to stay one more day by telling him that, tomorrow, she’ll show him a piece of evidence that will prove the fire was created by arson. The day comes, Nick shows up at her place, and says, “Where’s the evidence?” And she says, “Change of plans. First you’re going to tell me what happened to my daughter.”

The words “change of plans” should be a part of every screenwriter’s vocabulary. Why? Because YOU NEVER WANT THE READER TO GET COMFORTABLE. You don’t want them having a sense of where the story is going all the time. “Change of plans” throws the reader off. Cause now we’re going in a direction that wasn’t a part of the original plan. It’s exciting.

Not that you have to use those exact words (“change of plan”) every time. It’s more about you, the writer, occasionally changing things up so you don’t stay on that same predictable path the whole story.

Oh, one more thing. In a lot of the scripts I read, the bad guys never get the deaths they deserve. They get these quick weak deaths where they don’t suffer at all. This bad guy gets a terrible death and it’s awesome.

All this adds up to a really good screenplay. One of the best – maybe even the best – scripts on last year’s Black List. Definitely check it out!

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive (Top 25!)

[ ] genius

What I learned: There comes a time in a lot of scripts where a character will remember something about their loved one and share that experience with another character. These memories are one of the best ways to separate yourself from the average writer. Cause most writers have these boring on-the-nose memories they have their character recall.

“Oh, I remember when Wendy was 7 and she fell in the pool and she didn’t know how to swim and so I jumped in after her and I pulled her out and she wasn’t breathing and I’ll never forget giving her mouth to mouth. I thought for sure she was going to die. But, then, at the last second, she let out a breath. And it was at that moment that I knew my daughter was a fighter.”

Note how unimaginative that is. Note how 99 out of 100 writers would’ve been able to write the same thing. Real memories are unique. They have weird details. They don’t go according to plan. And they rarely line up with the five cliched memories that most writers use in these instances. Note how different, even a little bit odd, the chosen memory Dan Bulla uses for Jessie when she shares a story about Wendy…

“One time, I sat in the living room all night, waiting for her to come home. Just absolutely fuming. She finally snuck in just before sunrise. Didn’t see me sitting there in the dark. She shut the door. Locked it without making a sound. Then she went upstairs, straddling the steps so the stairs wouldn’t creak. And I didn’t say anything. I just watched her. And I remember feeling lucky. Lucky to witness that. Because I was seeing her. The real her.”