Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: An interplanetary explorer and a little girl crash land on earth 65 million years ago and must make it to their escape ship while avoiding the most dangerous predators the planet has ever known.

About: 65 inched its way towards a 13 million dollar opening this weekend, landing in third place behind Scream 7 and Creed 3. The subpar showing means we’ll probably never get the sequel, 66. Although, now that I think about it, that probably wouldn’t be a very good movie. Movie Trailer Voice Guy: “In a worrrllld consumed by fire and ash, where not a single living thing is still alive, one microbe is determined to replicate… in an attempt to repopulate the planet.” Yeah, probably won’t be at that one opening day. 65 was written by Scott Beck and Bryan Woods, who burst onto the scene several years ago with their breakout screenplay, A Quiet Place. This is their directing debut. The two first-timers had only 40 days to shoot the movie! For reference, Jurassic World had 115 days.

Writers: Scott Beck and Bryan Woods

Details: 93 minutes

Is there anyone who looks more like a movie star today than Adam Driver?

Is there anyone who looks more like a movie star today than Adam Driver?

You may be thinking I’m covering the third biggest story today (Scream 7 and The Oscars being 1 & 2) but everything about this project, this screenplay, this movie, is infinitely more interesting to me than Scream or the Oscars.

Scott Beck and Bryan Woods wrote the spec script, A Quiet Place, five years ago. How cool is it that the script you’re working on RIGHT NOW could be the next Quiet Place. And how cool is it that several years later you could be directing a movie with freaking dinosaurs in it?? I just think that’s the awesomest thing in the world. It definitively shows you the power of a great script.

If I were still writing screenplays, this is the type of script I would write. A huge concept with a simple story – the kind of thing that works both on the page and in the theater. At least, theoretically. Maybe I’m about to learn my latest screenwriting lesson after watching “65.”

65 follows an interplanetary explorer (from another planet – not earth) named Mills. Mills is dealing with a daughter who grows very ill and then dies. But work calls so he has to get out there and keep sussing out the universe.

Halfway through his latest trip, an undocumented meteor cluster hits the ship and he crash-lands on earth…. 65 million years ago. Everyone in the cryo-bays is dead except for a 10 year old girl named Koa. Unfortunately, Koa speaks another language, so her and Mills can’t understand each other.

Mills realizes that when their ship broke up, the escape pod landed about 10 miles away on the side of a hill. And it’s still in tact. So if they can get to that, they can pop back up into space and wait for a rescue vessel.

But it’s not going to be an easy trip. Cause it’s 65 million years ago when dinosaurs were at their hungriest. Right away, Mills is attacked by a little baby runt lizard thing that’s as big as a large dog. He barely survives. And that’s one of the weakest animals he’ll to have to deal with!

As they traverse the jungle and try and communicate with each other (poorly), Koa spots something in the sky casually zipping past the moon. (Spoiler) Later, Mills sees it too, and we’re introduced to the coolest plot development in the movie – that the anomaly is the meteor that wipes out the dinosaurs. Yes, our duo happened to arrive on earth just hours before the most devastating moment in the planet’s history. Talk about bad timing.

Now, getting to the escape pod takes on significantly more importance. But, along the way, our duo gets the attention of a couple of T-Rexes. Unknown to Mills, the T-Rexes stalk them from a distance to the escape pod where they perform an all-out attack on our heroes, determined to keep them here and make them suffer the same fate as them.

Probably the hardest thing to do in a script like this is come up with two characters who we actually care enough about that we want to spend an entire 100 minutes with them.

Beck and Woods do all the right *technical* things in this screenplay. They give Mills a traumatic backstory where his daughter died of an illness. That’s what we’re told to do as screenwriters. If we want to build sympathy towards our protagonist, create a sympathetic situation for them. What’s more sympathetic than a parent losing a child?

Then you have the girl. This is a helpless little girl who’s scared and who only cares about getting back to her family. Who’s more sympathetic than a helpless scared girl?

Beck and Woods also incorporate a screenwriting tip I routinely encourage, which is to make things difficult for your characters. You never want anything to be easy for them. So B&W make it so Koa speaks another language. This creates a language barrier. Now it’s difficult for Mills and Koa to communicate even basic things, which makes their task of working together that much more difficult.

So far, no mistakes have been made in this screenplay.

Then you have the most ruthless landscape in history. Literally every inch of the 10 miles you’re going to traverse has potential danger within it. This creates tons of tension and suspense, which is exactly what you want in a movie like this.

Finally, Beck and Woods create one of the coolest ticking time bombs I’ve ever seen in a movie: THE meteor that killed the dinosaurs. I had a huge smile on my face when that plot point was introduced. And I gave the writers extra credit because they combo’d the inciting incident (the crash) with that meteor’s orbiting rocks, setting up the meteor from the get go. This makes the meteor’s arrival feel believable as opposed to forced.

All that should add up to a great movie, right?

Yes.

But it didn’t.

Why?

I had to sit with this one for a while because I didn’t know the answer to that question right away.

All I know is that the movie had some cool moments for sure. But I wasn’t engaged the way I wanted to be. Something was missing. And I tried to figure out what it was.

The first thing you look at is the main characters. There is an enormous importance to the audience liking the characters in scripts like this because there are only two of them. There aren’t any other characters to cut to. So if we don’t love the main protagonist, and love the co-protagonist, as well as love both of them together, nothing else matters. Doesn’t matter if you have sixty gazillion dinosaurs. We’re going to be bored.

One of the mistakes Beck and Woods made was DKB. DKB (Dead Kid Backstory) is a cancer upon screenplays. It is the single laziest attempt to create sympathy the screenwriter has access to and, therefore, often creates the opposite effect of what the writer is going for. Especially if you do what Beck and Woods did here, which was to endlessly repeat DKB. We must have seen Mills’s dead kid a thousand times throughout the movie (in videos and flashbacks) despite the fact that she’s dead!

Dead Kid Backstory can work if the movie doesn’t depend on it. Gravity is a good example. We never once see Sandra Bullock’s dead kid. But that backstory was enough to motivate the character (in that she wanted to get away from earth) and that’s all we needed. I suppose there are a handful of examples of DKB working but that’s a handful out of thousands of attempts. It’s just lazy.

The other big mistake they made was having Koa speak a different language. I think I know why Beck and Woods did this. A lot of these adult-kid team-ups inadvertently descend into the kid being the “adult in the room.” They’re smart. They’re precocious. And it just ends up feeling false, with the kid snapping back at our hero in ways that would never happen in reality. By creating this language barrier, there was no way the script would fall into this trap.

But in a movie with just two characters and those characters can’t have any real conversations? You’re playing with fire. That’s a long time to ask the audience to spend with characters without a single extended conversation. People get restless. Even in Beck and Woods semi silent film, A Quiet Place, there were full conversations that were had.

This is where writers can sometimes get ahead of their skis. They want to make some profound silent film. But silent films are freaking hard to pull off. Audiences don’t have the patience – especially these days – unless you execute a perfect 10 on the dive. Mixing metaphors here – roll with me.

The thing that ultimately did the script in was there wasn’t enough variety. This is a challenge you’re always going to run into in a script like this. 90% of the scenes are walking through a forest with dinosaurs peeking around the corner. You need to find ways to mix it up. And the ways they mixed it up didn’t work. For example, they tired to have a cave scene. But it was sloppily constructed and not very clear. “Mixing it up” only works when the mixed up part is good. Duh but, yeah, that’s the reality.

Oh, and one other thing that hurt 65 was that a concept like this necessities a large scope. There’s a natural let down when that scope isn’t met. The reason a movie like Palm Trees and Power Lines, which also revolves around two characters, works, is because the expectations of the concept are low. It’s two people stuck in a small town. 65, however, is overwhelmed by its gigantic premise, which eventually swallows it up. The audience wants more than the movie can give them.

I’m bummed out. Because the movie wasn’t bad. It just wasn’t as good as I wanted it to be. And I’m going to cheat here with the rating because while there is no way this movie is worth the 20 bucks it costs to see in a theater, I do think it’s a strong streaming choice where the expectations are lower. And I have to support spec scripts and original material. We need more shots like this or else we’re going to be stuck with “The Creed Universe.” Dear lord help us all.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the stream

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: There is no other artistic medium that thrives in the present better than the movie. Movies are the most alive when they’re focusing on the RIGHT NOW. Therefore, when you put too much emphasis on things that happened in the past, you move away from what makes a movie work. That’s not to say you should never include the past in your scripts. The past informs who your characters are in the present. But if you’re going to go down that road, know that you are purposefully moving away from what makes a movie work. Therefore, you better have a great reason for it.

What I learned 2: One way to fend off repetitive storylines is to add more twists than the average screenplay. Add more shocking moments. 65 could’ve benefited from a couple more of those for sure.

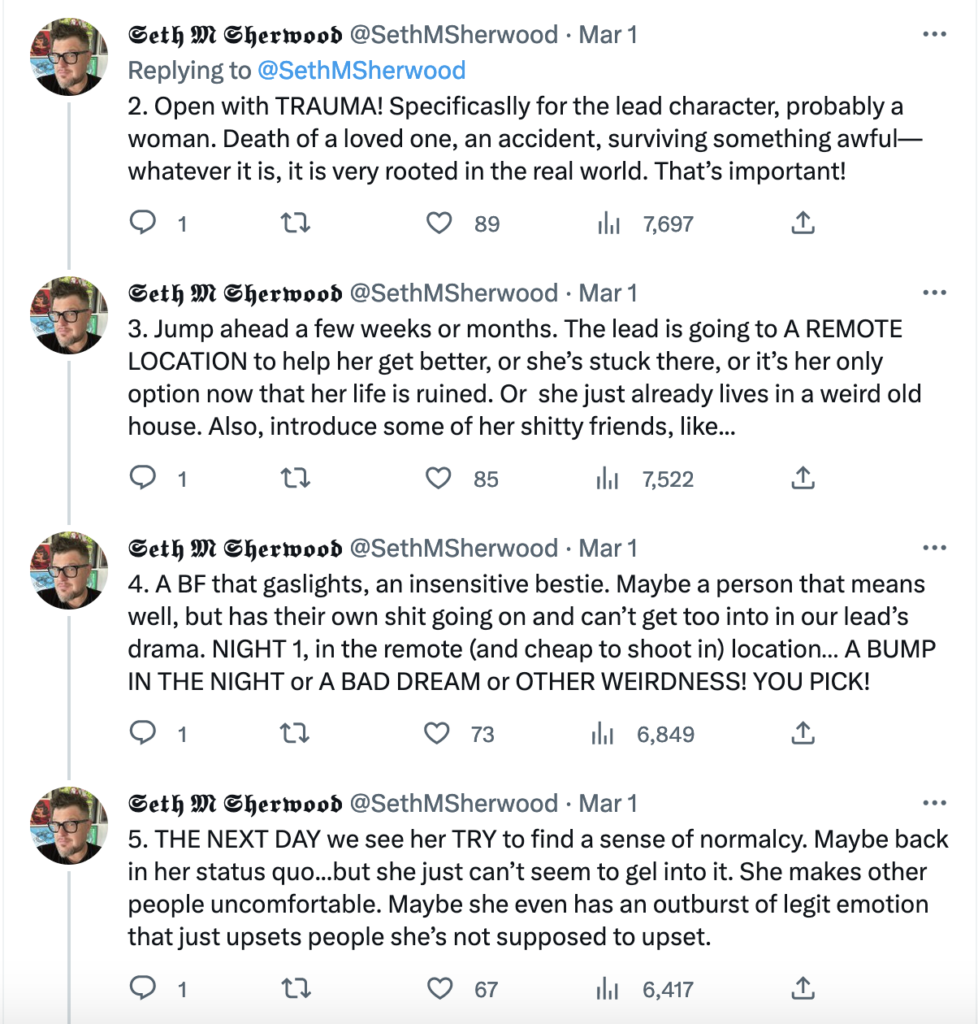

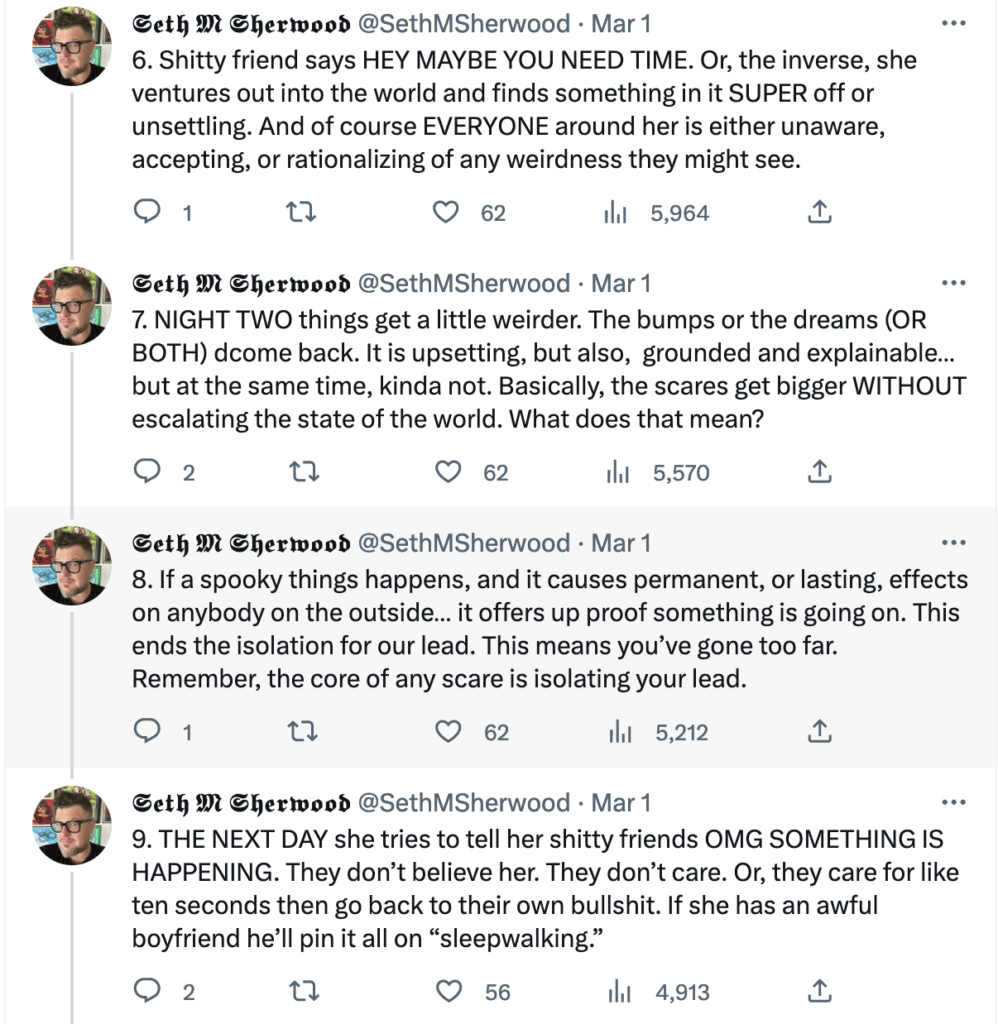

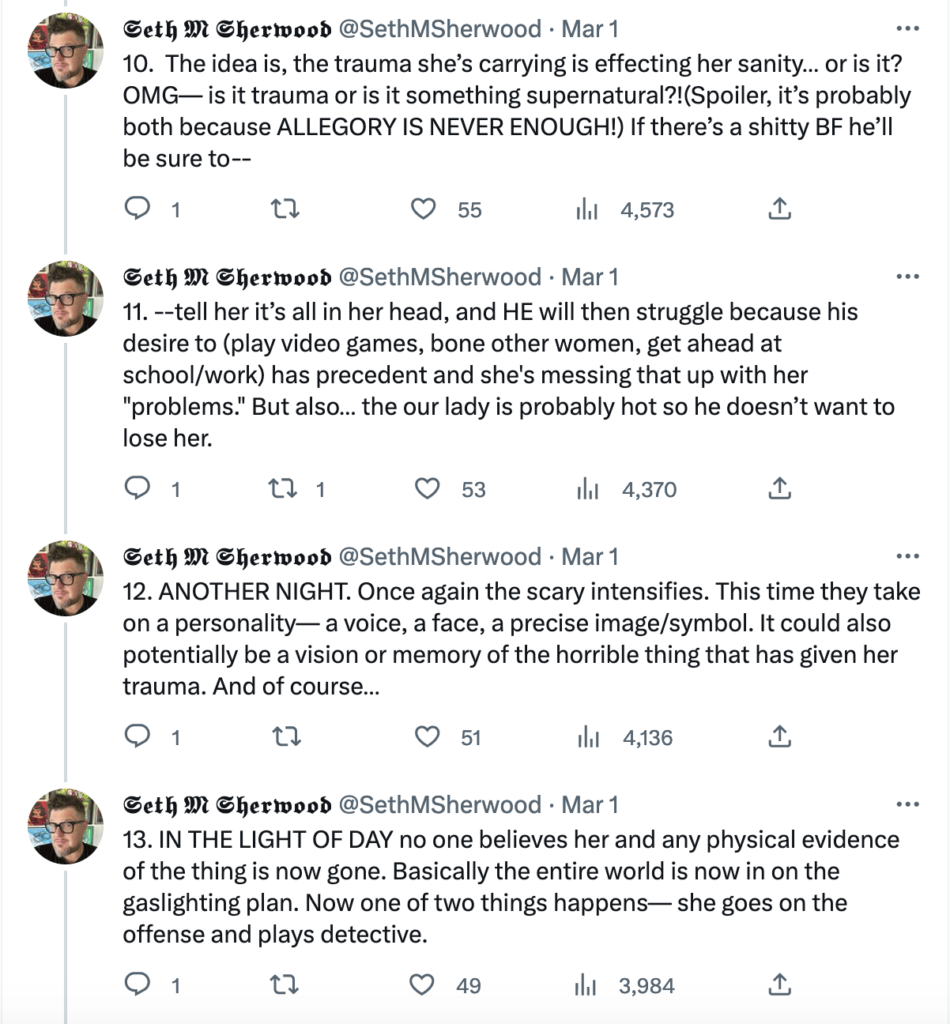

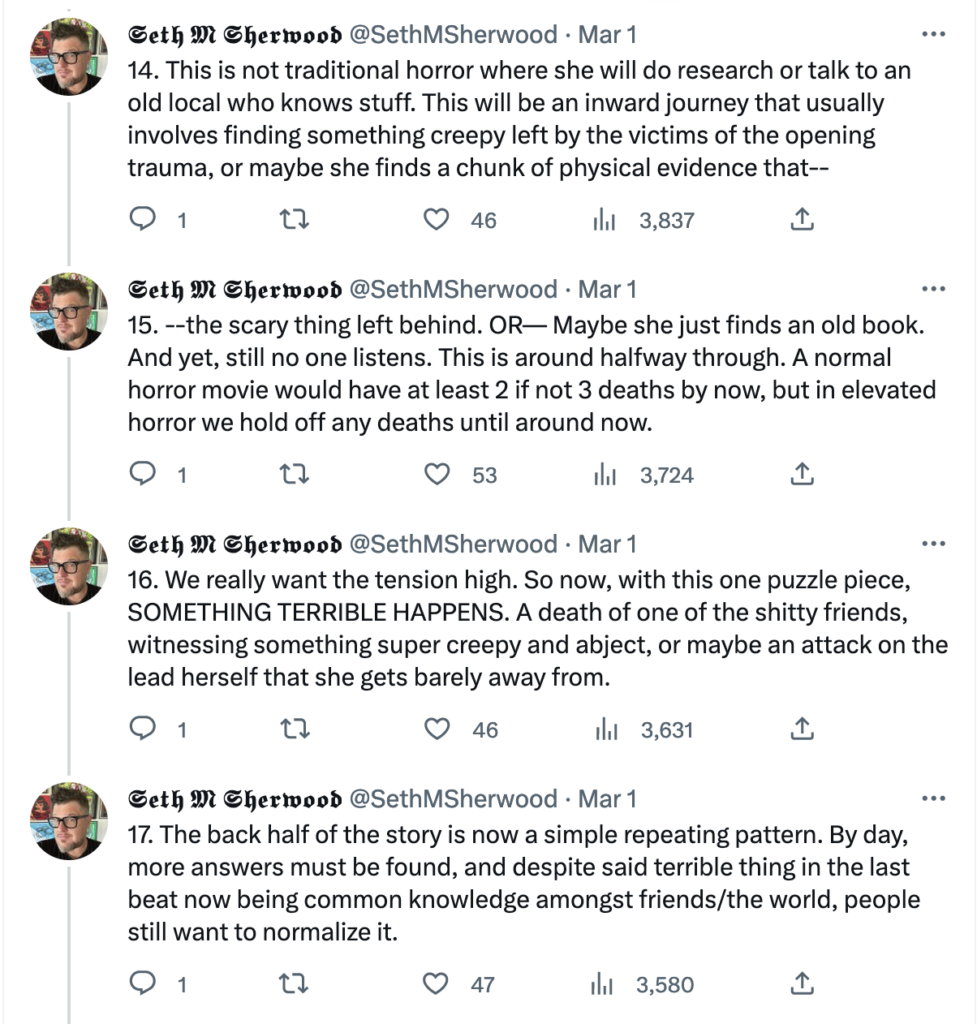

Yesterday, we discussed the drudgery of formulaic writing via Rob Liefeld’s 2 million dollar monstrosity, “The Mark.” Today, I’m going to thank Andrea Moss for pointing me to Seth Sherwood’s tweet thread, which takes on the current industry formula for writing “elevated horror.” Sherwood is probably best known for writing 2017’s, “Leatherface.”

1. HOW TO WRITE “ELEVATED HORROR! A thread in which I tell you exactly how to harness your PTSD and A24 the shit out of your script to the point you may actually be able to use your FSA health insurance fund to pay for it cause it’s basically therapy!

— 𝕾𝖊𝖙𝖍 𝕸 𝕾𝖍𝖊𝖗𝖜𝖔𝖔𝖉 (@SethMSherwood) March 1, 2023

The reason I found this thread so interesting is because Sherwood is making the point of how cliched every script he reads in this genre is by highlighting the absurdly common beats that he sees over and over again. Don’t get me started on how often I encounter the gaslighting boyfriend. At this point, you might as well just make “And the Gaslighting Boyfriend” the subtitle to every horror script that hits the market.

But this isn’t just about horror. Sherwood’s analysis can be extrapolated to represent every genre. Because every genre has its own formula that could be skewered in a similar way. If there’s anyone who knows this, it’s me. Cause I read these violating scripts all day long.

Because of this, I started getting a weird feeling while reading Sherwood’s thread. It was a feeling of, “Is writing a good story even possible anymore?” Because it’s all been done already. So why even try? What are you bringing to the table that hasn’t already been done to death? Aren’t you just matching these same story beats over and over again in your script?

Think about that for a second. Really think about it. Why do you write screenplays? I believe most writers write them because they want to show the world their unique vision, their unique ideas, their individual creativity. And then they want to be celebrated for that. But if your scripts are following the exact same formula that Sherwood lays out, aren’t you just copying what someone else has already done?

I grapple with this question nearly every day. Cause I still want to write stories in some form or another. But if I’m not bringing anything new to the table, then I don’t see any point in pursuing that endeavor.

For example, I love Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. I think it’s the perfect movie. So let’s say I write a high school script about some teens breaking the rules. Is there any chance in my movie being better than Ferris Bueller? No. Not in a million years. So what am I doing here? Trying to write the bad version of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off?

Getting back to Sherwood’s thread, something surprising happened in the comments. A writer pointed out, “That’s the exact formula for The Night House and that movie was awesome.” To which, Sherwood agreed. Then someone else said, “That’s the exact plot for The Howling.” Sherwood acknowledged he was right.

Other movies that he acknowledged following this formula were Midsommar, The Witch, Hereditary, Smile. All movies that got either really high critical marks or did well at the box office.

And even though I learn this lesson once every two months, I always have to learn it again. While, yes, formula can hurt you, it can also allow your script to thrive if the execution is strong.

Now, that’s a vague term: “Strong.” It doesn’t really mean anything without context. So let me give you an example. Every horror script starts with a cold open. Something usually freaky and mysterious happens in the first scene. Well, how you EXECUTE that cold open can range from boring and uninspired to exciting and original.

I read an amateur horror script a while back that had a girl hanging out in her house – her parents were away for the night. The doorbell rings. She goes to the door. She checks outside. There’s no one there. She shrugs, goes back to the living room, plays on her computer for another 30 seconds, and then we see a shadow shoot across behind her. She turns around, peers into the darkness of the hallway. Can’t make anything out. She turns forward and, standing in front of her, is a freak in a mask who then kills her.

Contrast this with the opening of It Follows, where we see this barely dressed girl run out of her house at dawn, continuing to look behind her as if something is chasing her. We can’t see anything though. Her fear is palpable as we try to piece together why she’s acting so strange. She’s so scared that she gets in a car and drives as far away as she can. She hides out on a beach, looking off in every direction, before we cut to the next morning where she’s dead and looks like someone stuffed her inside a trash compactor.

Both of these scenes are following the formula of a cold open. But one gives you the “seen it a million times before” version that doesn’t try to elevate the scenario. The other gives something thoughtful and original that makes you want to keep reading in order to get answers on what happened.

You have this exact choice – lazy and uninspired versus unique and exciting – 15-20 times throughout your screenplay. You have that choice in the way you introduce your protagonist. You have that choice with how you handle your inciting incident. If you’re writing a haunted house movie, you have that choice the first time your characters enter the haunted house.

How are you going to innovate and make these common moments feel fresh?

In addition to this, you have to create a protagonist who we both relate to (we’re sympathetic to their situation because it’s similar to something that’s happened to us) and who we believe. The character must act in a manner that is consistent with real life and, therefore, feels like a real person. As opposed to a character who just acts however the writer wants them to act in the moment, even if by doing so they constantly betray the original character that was introduced.

This is why The Night House worked so well. You believed Rebecca Hall’s character. For those who haven’t seen the film, Hall plays a grieving widower who is cleaning out the lake house that her and her dead husband used to stay at. She then starts seeing things that indicate he’s haunting the place. Rebecca Hall’s part of the mourning widow was written so authentically that we were pulled into her grief.

To expand on that. You’ve gone on a million dinner dates, right? There are no surprises when you go to dinner with someone. And it has acts, just like a script. You’re going to get the menu. Your’e going to choose something to eat. You’re going to chat and eat. You’re going to get dessert. You’re going to hopefully get her to pay the bill and then leave. However, if the person you’re with is engaging and fun and you guys are vibing, that dinner date that you’ve had a million times before all of a sudden feels fresh and new, because you like the company.

We care so much that Rebecca Hall’s character is going to come out of this okay that experiencing this with her is the equivalent of great company on a date.

So, the next time you write a script and you worry, like me, that you’re rehashing a formula that’s been used to death, and, therefore, are unconvinced you can give the reader a fresh experience, remember the two rules I just laid out above.

For every major beat in your story, try to come up with something a little (or a lot) fresher/original than what’s usually used in that scenario. And then give us a relatable genuine hero who we’re really rooting for. Those two things will help you supersede the limitations of formula which will result in a great script even if it’s, technically, similar to every other movie in that genre.

From the creator of Deadpool comes a 2 million dollar spec sale from the 90s that was supposed to be the next huge Will Smith franchise. What happened??

Genre: Action/Adventure/Supernatural

Premise: A mild-mannered campaign worker receives “the mark,” a special ancient marking that gives him all sorts of special powers.

About: This was supposed to be a huge one. The script was purchased in the 90s for 2 million bucks. It was going to star Will Smith. None other than Steven Spielberg was going to direct. Smith’s Independence Day producers, Devlin and Emmerich, were set to produce. And, oh yeah, it was written by the co-creator of Deadpool, Rob Liefeld. Scripts don’t come with much more pedigree than that. According to Liefeld, the project fell apart because of merchandising and producing points. Although something tells me it fell apart after someone read this draft.

Writer: Rob Liefeld

Details: 1997 draft

The Matrix.

Wanted.

National Treasure.

Raiders of the Lost Ark.

The Devil’s Advocate

The script has it all.

In many ways, this project was the pinnacle of the 90s Hollywood deal. You had this sexy high concept idea. You had mega-star Will Smith. You had Spielberg joining you in the pitch room. Let’s be honest. They could’ve pitched “Bathroom Boy: The Tale of the Lost Toilet Paper” and sold it in the room that day.

But instead they sold The Mark.

And we’re all left to wonder if this was the final nail in the coffin for giant script sales. Cause this script is awful.

We start in Nazi Germany during World War 2 cause of course we do. Some evil German commander named Gates is storming into a Jewish apartment building to find the Jewish man who holds “the mark” on his hand – a special tattooed stamp that means you have powers!

The elder owner of the mark passes it down to his son, Jacob, who then leaps across buildings in a single bound, escaping the evil Nazis, as well as escaping the boring scene.

Cut to modern day and you bet your bottom dollar we got a New York apartment that’s got dirty clothes on the floor, that’s got beer cans on the side table, and, woudln’t you know it, when the alarm clock goes off, a hand shoots into frame and throws against the wall.

Apparently Chat GPT time-traveled back to 1997 and answered the question, “How do I write the most cliched character introduction ever?” And that’s what it came up with before traveling back to the future.

The cliched hand belongs to Mike Collins, who gets a knock on the door soon afterwards and do I even need to tell you who it is? Cause if you don’t know, you’ve never seen a movie before. It’s the landlord! And she wants her money. Cause Mike is late with the rent.

Mike makes an excuse then meets his elder friend, Jacob, by the news stand – yes, Jacob is the same Jacob from before. Jacob tells Mike to bet on the Bulls against the Knicks if he wants to make some money. Mike heads to his campaign job where the mayor is going to be running for president soon. At the end of the day, the Bulls beat the Knicks.

Mike goes to thank Jacob except Mike finds Jacob shooting balls of energy out of his hands at two dudes in the alley. Jacob gets hit by a enemy energy ball and, as he lays dying, PASSES THE MARK TO MIKE! Mike runs away, realizing, in the moment, that he has super speed. And then he also has super strength.

He’s terrified of all this new power and he tries to hide. But he’s soon visited by this chick named Falkon. Falkon then takes Mike to her secret hideout which is in…. Wait for it, the Statue of Liberty. Falkon explains to Mike that he now bears the “mark” and, therefore he’s “the one” and that the evil Jonathan Gates (from the opening) is going to do everything in his power to get that mark because the planets are aligning soon and he needs to have it do destroy the world or something. Yada yada yada. The end.

The Mark may be one of the most blatant examples of how influenced we are by the time that we’re writing in. This was written squarely in 1997 when everyone was writing these scripts.

You’ve got the nobody everyman protagonist. You’ve got the special power that’s passed on from generation to generation. Our character is known as “The One” (although, in the writer’s defense, Matrix hadn’t been released yet). You’ve got Nazis. You’ve got the “learn your powers” fun-and-games section.

I love reading scripts like this for this very reason – to remind you not to write the same stuff that everybody else is writing at that time. You have to be able to step out of your body, travel 20 years into the future, and look back at your current script through that lens of, “Does my script read like every other movie that was being released at that time?” And if the answer is yes, your script either needs a major overhaul or to be thrown in the trash.

I always say that a screenwriter becomes a screenwriter when they watch other movies and don’t think, “Ooh, that’s cool, I’m going to include that in my script,” but rather, “Ooh, that’s cool, now I can’t use that in my script.” You learn to actively avoid the things that everybody else is doing.

But let’s play a different game for this review. Which is, if I read this in 1997, would I like it? And the answer to that would be no. I’ll tell you why. Because the secret base is in the Statue of Liberty. Let me repeat that: THE SECRET BASE IS IN THE STATUE OF LIBERTY!!!

I have seen many a questionable writing choice in my day. I’ve seen scripts written entirely on one’s cell phone. I’ve endured twenty-minute scenes of characters watching The Shining… IN SPACE. I’ve read not one, not two, but THREE Mattson Tomlin scripts, which, combined, exhibited the thoughtfulness and sophistication equivalent to a fifteen minute visit to the bathroom.

But giving your characters a secret base in the Statue of Liberty in a non-comedy is up there with the dumbest creative choices I’ve come across. I’m not even sure Mattson Tomlin would do something this dumb. I mean, are you even trying at that point?

As soon as that happened, I was out. The script was trending downwards before that. That brought it into “bottom of the ocean” territory.

Another problem is that Liefeld adheres to formula so rigidly that it strangles the story’s ability to live. This is a debate that’s raged on for years in the industry and this script shows you why. Because every single beat of this script is lined up with the Blake Snyder beat sheet and, as a result, there’s no life to it.

It’s just a screenplay beat sheet. It’s not a real thing that happened.

Which is what you’re trying to achieve, by the way. You’re trying to make your movie feel like something that really happened. The second we don’t feel that, we start seeing your movie as a produced fake product rather than an experience to get emotionally wrapped up in.

I think structure is good. But it has to be invisible. You can’t be so clunky in your construction of it that all your plot pillars are visible. You have to hide it, like exposition. Which basically means that your characters are dictating what happens as opposed to the writer dictating what happens.

When the Terminator walks naked into a bar and finds a biker his size and tells him to give him his clothes, we feel that as a genuine moment because the Terminator needs to blend in to society. And he can’t blend in without clothes. It’s imperative that he do this to succeed at his mission.

Conversely, when Captain Marvel steals a guy’s jacket and motorcycle who tells her to smile, that moment is 100% created by the writer. It doesn’t need to happen for the story. It’s just the writer wanting to get this thing in there they want to say.

Structure works the same way. If we feel like, “Oh, now we get the scene where the guy gets a tour of the secret base,” and, “Oh, now we get the scene of him practicing his new powers,” and “Oh, now we get the scene where the love interest pops in,” then we start falling asleep.

A script dies the second the reader knows what’s going to happen three minutes from now. Once they can always tell what’s going to happen in three minutes? Your script is dead to the world cause it’s terrible.

You’ll never be able to perfectly hide everything, of course. But you have to be good enough to hide most of it.

To be fair to Liefeld, this doesn’t feel as cliched if we’re reading it in 1997. But it doesn’t matter because there is literally nothing to offset the cliches. Every single choice, from the main character to the love interest to the powers to the rules, are so insanely bland that I don’t know how he was okay with others seeing these pages.

Try.

At the very least, try.

That’s all I ask from writers. Let me see that you’re trying and, even if you write a bad script, I will respect you for giving it your all.

This script had zero try-factor.

And you can read it yourself! – The Mark

[x] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: There’s a famous moment in the movie National Treasure where Nicolas Cage’s character has to use the Constitution, which is encased in bullet proof glass, to deflect some bullets. The reason this moment is so famous is because it’s ironic. It’s clever. That you’re using this 300 year old document to defend yourself. Having a secret base in the Statue of Liberty is not ironic. And because of that, it comes off as lazy and dumb. So, if you’re tasked with coming up with something and you don’t know if it’s cool or stupid, do the irony test. If there’s some irony there, it’s probably cool.

The hottest horror director in town charges in and grabs a juicy new horror story.

Genre: Horror (short story)

Premise: When a new home is moved onto an empty lot in a Texas town, it begins haunting all the houses around it.

About: What did I tell you guys? Write those short stories! Especially in the horror space. They’ve become the new million dollar spec sale. This short story got everyone around town hot and bothered and ended up in the hands of the scalding Zach Cregger (Barbarian), fetching just shy of 1 mil. The story is written by a newbie writer, Victor Sweetser, who was actually pitched the story from someone in the business who had seen his writing from Reddit and then Sweetser wrote the story and published several parts of it on Reddit. It was the person who pitched Sweetser who helped set the whole thing up for a bidding war. Cregger will team with Roy Lee at New Line (It) to make the film. The two are collaborating on another hot project that sold recently called “Weapons.”

Writer: Victor Sweetser

Details: 34 pages

A while back I talked about how Barbarian had one of the best opening acts I’ve seen in years. Apparently, Hollywood agreed, because since then, the director, Zach Cregger, has become the town’s newest obsession. He has set up not one, not two, but THREE different projects this year, all of which resulted in big auctions with lots of bids.

This is his latest sale and it comes from the newest get-rich-quick scheme for writers – a killer short horror story.

17 year old Chloe lives on a normal block in a Texas town, the kind of place where nothing much goes on. Her days consist of looking forward to seeing her boyfriend, Mason, who has his faults but is, overall, a pretty awesome partner. Chloe also likes to slum around town with her kinda dumb best friend, Kat, and her dainty brother, Jake.

Then one day, a house moves onto the block. That’s right. Like, an actual giant Victorian house is wheeled into the one open lot on the block and plopped down there. Everyone is confused by this but Chloe and Mason see it as a new opportunity to have some fun so they go inside that night. Except only one of them comes out. Mason, simply, disappears!

The next day, at school, while in class, Chloe and her class see a naked guy on the school’s football field charging at them. It’s Mason! Mason sprints, with hate in his eyes, straight at Chloe, bashing into the window and hitting the dirt. Something happened to him in that house. Something bad.

Chloe does some research and finds out that the house owners bought the house for FREE on Facebook. The only stipulation was that they move it out of its New Orleans neighborhood. So they moved it here. Quickly, everyone on the block starts going crazy. One homeowner sets himself on fire! Another drives their car straight into another neighbor’s house. Clearly, this house is doing something to everyone.

Chloe knows that it’s only a matter of time before she’s next so she recruits Jake and Kat to go to New Orleans and learn how to stop the house. Once there, they get the low down. The house was responsible for destroying an entire neighborhood! Everyone had gone crazy. Chloe now knows that if she’s going to stop the madness, she has to go back to Texas, go into the house, and face whatever it is that’s doing this.

One of the hardest things to do in writing is find a new spin on an old idea that actually feels new. As writers, we’re really good at convincing ourselves that we’ve come up with a new spin when, in actuality, we’ve just come up with a weaker version of a previously successful idea.

It’s like saying you’ve come up with a new spin on the disaster genre by having a giant earthquake hit Portland instead of Los Angeles. Sure, your disaster is taking place in a different city. And that does make it “different” by the letter of the law. But does that difference make it desirable to audiences? That’s the real question. And a Portland earthquake movie does not.

I do have sympathy for writers looking for that “same but different” idea because sometimes, a writer will come up with only the tiniest change and still, somehow, strike gold. Like M3GAN. It’s Chucky with the only difference being now the doll is AI. Other than that, IT’S THE SAME FREAKING MOVIE!

So I’m not going to pretend like this is an exact science but I do think that Occupant hits that “same but different” mark as I’ve never seen a story where a haunted house is moved into a neighborhood.

It’s a pretty cool concept and I liked the idea of the haunted house making the entire block haunted. Not only was it different but, from a story perspective, it forces your hero to be active. Because, since Chloe lives on the block, she has to figure out how to stop this haunting or she dies too.

Chloe was one of the things I liked best about the short. Often times, in horror screenplays, writers make the mistake of having their hero wait around for the next scare. Not only is Chloe active within her own neighborhood, but once things get really bad, she travels to another state to figure out how to defeat this thing. So Chloe alone pushes – dare I say SHOVES – this narrative forward.

Moving on to the adaptation of this story, short story writers who are using the medium as an avenue for a spec sale need to make sure that the Hollywood readers can see places within the story that can be expanded for the movie. Or else your story won’t feel like it has enough meat for a feature.

So I’m happy to say I could see the whole movie here. There’s this section that the writer rushes past where, individual neighbors start doing crazy things, such as lighting themselves on fire and I realized, you could make all of the characters on this block bigger characters for the movie. And then you can expand this section where they all start going crazy because of the haunted house’s effect. Cause I felt that section was the one with the most potential. So I was actually kinda surprised the writer zipped by it. But it’s going to work great on-screen. It’s such an obvious place for the screenwriter to expand.

The story also has a great villain. There are these figurines and images on old dishes and vases throughout the house of this “twisted woman” who looks like she’s trying to do the most advanced yoga pose ever. Only later do we learn that this is the woman who’s haunting the place. And, naturally, when we finally see her in twisted form, we’re terrified.

So, I liked a lot about this story. However, it still only gets a “worth the read” from me because, in the end, there’s nothing truly stand-out about the short. If feels like, if there are any missteps in the production, that it could end up being a Scream knock-off. And Scream isn’t good anymore. So that’s not what you want.

Which, I guess, begs the question: Which Cregger is showing up for this movie? Is it the Cregger who directed the first 50 minutes of Barbarian? Or is it the Cregger who directed the second 50 minutes? Because those were two completely different movies. If the first 50 Cregger shows up, this is going to be good. Cause the story is solid.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Even if you nail everything in a fun concept like this, you’ll still find yourself struggling to sell it if you haven’t come up with a visually scary villain. If this haunted house is just haunted by some old creepy dude, that’s not enough. This weird twisted woman conjures up a much more aggressive and freaky image. Which is exactly what you want. You want that reader imagining that creepy villain on screen. That’s the exclamation point for selling a horror story like this. Because once the producer can see that unique freaky villain that they can build an entire marketing campaign around, THEY’RE IN.

What if I told you that there was a new horror film coming from a Shyamalan but that it WASN’T M. Night Shyamalan? Would you believe me? Would I believe myself? Alas, this newsletter’s big script review comes from Night offspring. Are we ready for a whole new generation of twist endings? I also share my thoughts on the new Mandalorian season and if it’s possible to die from cuteness overload. I give you two big tips on movie idea theft, one regarding a scenario you shouldn’t worry about, and another about a scenario you should. I give you a dialogue book update, some tips we can learn from a couple of recent Amazon purchases, and my assessment of, quite possibly, the most confusing movie I’ve ever come across.

No post today. Just a newsletter. So if you want to participate in the conversation, e-mail me to get on my newsletter list and I’ll send it over to you immediately (assuming I’m not asleep). carsonreeves1@gmail.com